Ian here—

Earlier this week, I sat down with some friends to play David OReilly’s Everything (2017). We were all suitably hyped, and ready for an evening of being different things while chuckling over the political indefensibility of object-oriented ontology. (Yes, really. We’re those people.)

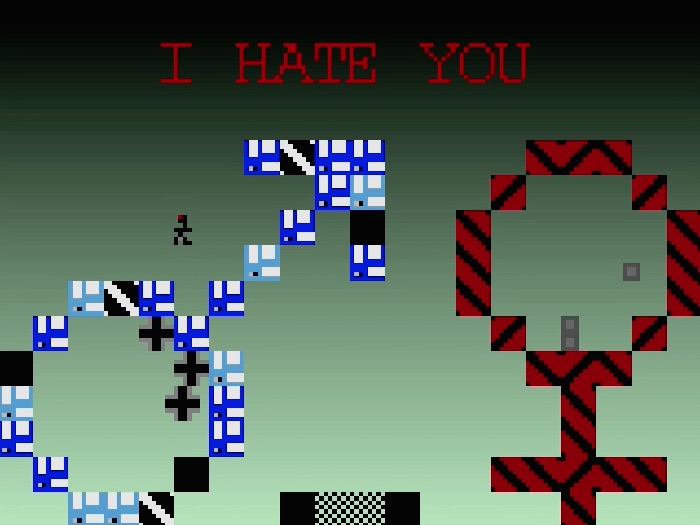

But our evening hit a snag. Somewhere along the line, in our first playthrough, beginning as a cougar, we encountered a weird bug. One of the little “gain a new ability” thought bubbles failed to pop up in the environment. No matter how far we traveled, or how many objects’ thoughts we listened to, we simply could not unlock the ability to scale up or down into bigger or smaller entities. We were doomed to be a cougar. (Or, cougars, rather. We were able to expand our ranks, and become about a dozen cougars, rolling across the rocky landscape. But being a dozen rolling cougars is small consolation in a game that promises that you can be, well, everything.) For 75 minutes, we wailed at the screen. “I thought you could be lint particles and galaxies and stuff!”

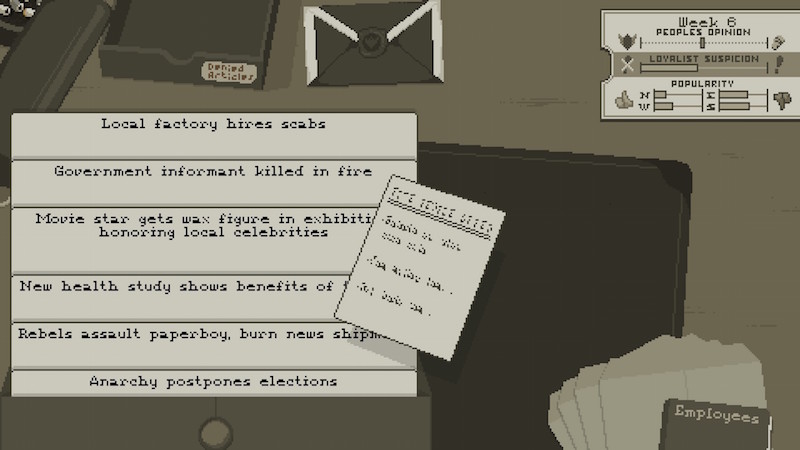

We tried, to no avail, to look up walkthroughs for Everything. Everywhere we looked, we found glowing reviews of how chill the game was, how it allowed you to sit back and let the experience of being everything wash over you. We couldn’t fathom how we got stuck in a game with no real objectives. To pour salt in the wound, the game seemed to be actively mocking us. “As long as you keep moving, in any direction you choose,” thought a tree, “that will take you where you need to go.” “Over time,” thought a rock, “you might find there’s no right or wrong path to take here.” We were seriously stuck, and the only feedback we were getting were Zen aphorisms that told us to take it easy and not worry so much.

Eventually, we deleted our save file and started over. Thankfully, this solved the problem, and we spent the rest of the evening enraptured. But it did get me thinking about the trickiness presented by purposefully inscrutable game design.