Ian here—

This post is part of a series that borrows the term process genre from Salomé Aguilera Skvirsky’s work in cinema studies, and explores its utility for videogame analysis. A quick definition: “process genre” films are films about labor, films that focus on processes of doing and making, that are fascinated with seeing tasks through to their completion. They are deliberately paced, meditative, and often political, in that they cast a penetrating eye on labor conditions. Are there games that the same chords? Posts in the series so far can be seen here.

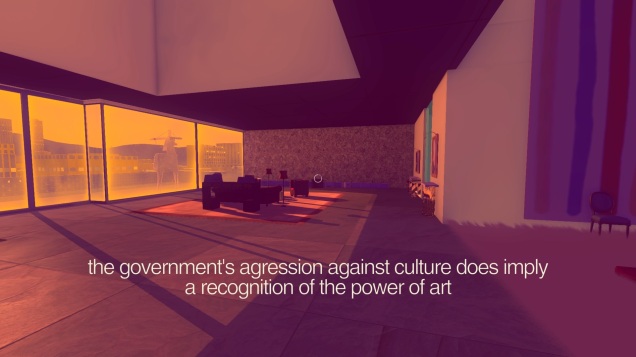

I reserve the right to sporadically post future entries in this series, but with Sunset (Tale of Tales, 2015), it really does feel as if things have come full circle. As I laid out in the first post in this series, the process genre finds its most archetypal manifestation in Belgian filmmaker Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 Commerce Quay, 1080 Brussels (1975), and Skvirsky has been tracking its development in contemporary Latin American cinema. Sunset was created by Belgian artist duo Auriea Harvey and Michaël Samyn, and is about the daily life of a housekeeper in a (fictional) Latin American country. The parallels are easily drawn, but there’s also more going on here than this brief description suggests.