Ian here—

This post is part of a series that borrows the term process genre from Salomé Aguilera Skvirsky’s work in cinema studies, and explores its utility for videogame analysis. A quick definition: “process genre” films are films about labor, films that focus on processes of doing and making, that are fascinated with seeing tasks through to their completion. They are deliberately paced, meditative, and often political, in that they cast a penetrating eye on labor conditions. Are there games that the same chords? Posts in the series so far can be seen here.

I reserve the right to sporadically post future entries in this series, but with Sunset (Tale of Tales, 2015), it really does feel as if things have come full circle. As I laid out in the first post in this series, the process genre finds its most archetypal manifestation in Belgian filmmaker Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 Commerce Quay, 1080 Brussels (1975), and Skvirsky has been tracking its development in contemporary Latin American cinema. Sunset was created by Belgian artist duo Auriea Harvey and Michaël Samyn, and is about the daily life of a housekeeper in a (fictional) Latin American country. The parallels are easily drawn, but there’s also more going on here than this brief description suggests.

Introduction: the Gone Home test

Ever since August 2013, every time I play a new game that falls somewhere in the “indie game”/”art game” spectrum, there’s a process of assessment going on somewhere in the back of my mind. I’ve come to refer to it as “the Gone Home test.”

It goes something like this: Let’s posit that I am an educator, and that I am teaching a college-level course on digital storytelling, or new media, or something along those lines, offered in an English department, a Cinema Studies department, or some sort of interdisciplinary Comparative Media Studies context. I can only find room on my syllabus to fit one commercially released, mass-audience videogame. My default choice would be to assign Gone Home (The Fullbright Company, 2013).

As I’m playing through the game, then, I ask myself: is there a compelling reason for me to assign this, instead? Does this game, too, realize that stories can be related through means other than text logs or audio logs? Does it make a perfect pairing with Henry Jenkins’ “Game Design as Narrative Architecture” (which, presumably, I’m going to assign for reading this particular week of the syllabus)? Is it short? Is it nonviolent? Is it approachable for non-gamers? And, most importantly … and most difficultly …is it better than Gone Home on at least one of those counts? Is there something I could use it to teach that I can’t use Gone Home to teach?

I admit, it’s both a completely unfair test, and a completely esoteric one. Most people who play games aren’t educators, constantly asking themselves if they can spiff up their syllabus with new releases. But it’s forever in my mind, and even the games that have most entranced me since 2013 have had a tough time passing it. Consortium (Interdimensional Games, 2014) didn’t. Cibele (Star Maid Games, 2015) didn’t. Nor did That Dragon, Cancer (Numinous Games, 2016), or Firewatch (Campo Santo, 2016).

Sunset, though … Sunset passed my Gone Home test. Sunset gives me an opportunity to address the particularities of videogames as a time-based medium in a way that Gone Home does not. And it should be little surprise, following the posts so far in this series, that the particular time-based aspects of games that Sunset highlights have to do with process, habit, and ritual.

The time that remains

There’s been an unspoken source of tension as I’ve draw parallels between the process genre in film and the process genre in videogames in my past posts. One of the central features of the process genre in film is an unhurried pace. Process films such as Cousin Jules (Dominique Benicheti, 1972), La Libertad (Lisandro Alonso, 2001), and El Velador (Natalia Almada, 2011) fit comfortably within the designation of slow cinema, lulling viewers into a languid and relaxing pace. Several of the games I’ve written about in this series, however—Papers, Please and Cart Life in particular—enact very strict time pressures upon their players. The labor in these games proceeds at a frantic tempo, with players facing severe in-game punishment if they fall too far behind.

There are, in fact, plenty of games that hew closer to the relaxing pace of process films. In particular, there’s the cluster of “weird German (and sometimes Czech) simulations of un-glamorous labor” genre that has become mesmerizingly popular in recent years. 2016 alone gave us Farming Simulator 17 (GIANTS Software, 2016), American Truck Simulator (SCS Software, 2016), and Bus Simulator 16 (astragon Entertainment, 2016), all of which could be profitably analyzed within the context of the process genre. (One could even argue that they form a sort of “slow videogames” movement, complimenting the current popularity of slow cinema in the international arthouse circuit.) If I were undertaking this comparative study as a book or an academic article, I would undoubtedly do my due diligence, and play the aforementioned games. But I’m only doing this for a series of casual blog posts (for now, anyway), so I’m going to stick to talking about things I’ve played.

Which brings us back around to Sunset, and its pacing. In Sunset, players take on the role of Angela Burnes, a young African-American woman who, upon graduating college in the early 1970s, decided to travel the world, and ended up in the South American nation of Anchuria. Anchuria’s right-wing government has cracked down, instituting a travel ban for foreigners. The political climate is quickly heating up, and rebellion is spilling into the streets.

Any of this sound familiar? (And no, I’m not talking about Papers, Please.)

As a US citizen, Angela is now stuck, forced to find employment as a housekeeper as she waits out the nation’s political turmoil. For an hour each night, from 5:00 PM to sundown at 6:00 PM, she cleans the penthouse apartment of Gabriel Ortega, an art critic and curator with ambivalent ties to the current presidential administration.

One might be tempted to call the game a combination of the voyeuristic storytelling-by-snooping of Gone Home with the process-based elements of menial labor simulation, but that formulation isn’t particularly insightful (or even accurate, really). What it misses is the game’s strong sense of biding time. On the macro level of the game’s plot, Angela is biding time until the the current government or its successor will allow her to finally leave the country. This is reproduced on the micro level of each in-game day, in which work becomes just another mode of waiting, of passing time, of waiting out a potential revolution in a high rise sanctuary.

Some evenings in Sunset are as legitimately busy as any day in Cart Life. Sometimes Angela has been left a full to-do list that will take up an entire hour. (This is more likely to be the case early in the game, before players have learned the layout of the apartment, and when they are likely still confused by Ortega’s terse directions.)

More often, though, there won’t be enough tasks assigned to fully fill out an in-game hour. “I’m not sure how thorough I’m supposed to be in my cleaning work,” Angela notes in one of her early journal entries. “Should I only do as he asks? That wouldn’t even require half an hour.” She muses that perhaps Ortega doesn’t know how to give cleaning directions, because he himself has never had to clean.

Leaving early is always an option, but there are in-game ways for players to pass the time if Angela has a spare 20 minutes before Sunset. They can find the notes that Ortega occasionally leaves around the apartment, and chose a response for Angela to write on them. They can peruse the records that Ortega sometimes leave lying about, and plot them on the turntable. There’s also a radio, if one wants to listen hear about Anchuria’s cultural history and current political situation. Angela has the aforementioned diary she can write in (as long as the player finds the one chair she can sit in to do that, which moves around as the game progresses). She can even set aside time each day to practice the piano.

Players are encouraged to indulge in such side activities more and more as the game progresses. From September 9, 1972 to November 18, 1972 of Sunset‘s in-game calendar, Ortega is on an extended out-of-town trip, and Angela’s responsibilities are whittled down to little more than just placing his mail on the dining table. Players in a hurry might lose interest in this section, rushing through toward the finish. But those who poke around will be rewarded with art projects Angela can take on to re-decorate Ortega’s home in his absence, along with new records, radio shows, and sheet music.

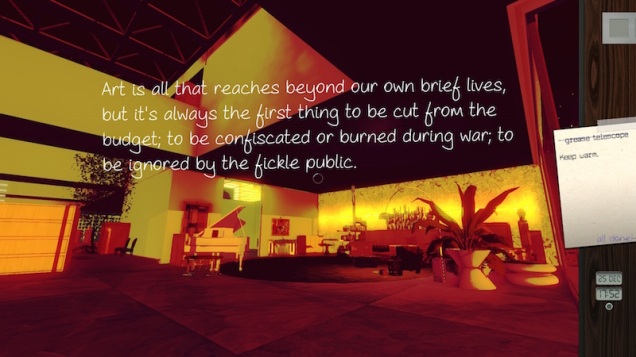

This split between labor and leisure could be described as a function of the game’s world-building: details about the political climate of Anchuria, Ortega’s life, and Angela and Ortega’s budding friendship (romance?) are left hidden in the margins, accessible to intrepid players willing to put in the requisite time. This is true, as far as it goes, but it makes the game seem far more conventional than it is. Tale of Tales seem less interested in straightforwardly delivering exposition as they are in the careful crafting of empty moments.

I wrote back in my entry on Cart Life that, despite sharing some similarities to neorealist cinema in its basic description, the rapid pace of Hofmeier’s game broke from the sedate tempo so often associated with neorealist cinema (Italian, and otherwise). Sure, the game has slow moments—Melanie walking her daughter home from school, for instance, the two of them conversing about when one should say “Black” versus “African American”—but work itself is presented as a whirlwind rush.

But work isn’t always a whirlwind rush. Sometimes, labor and leisure weave together. Boredom and stress coincide. Private moments take place during professional tasks. The “maid’s getting out of bed” scene of Umberto D. (Vittorio De Sica, 1952), celebrated by André Bazin as a moment in which cinema becomes an “asymptote of reality,” consists entirely of this sort of interweaving.[i] Maria the maid gets up, walks to the kitchen, looks at cats on roofs out the window, sprays some ants off of the wall with water, grinds coffee, closes the door with her foot to ensure herself privacy as she cries about the likely implications of her unplanned pregnancy. Her labor is utterly shot through with private, quiet, empty moments, with a furry of unspoken emotions just below the surface.

Sunset aims for a similar balance. At one point in the game, after Angela has suffered an enormous personal loss, Ortega’s to-do list for he reads only “do what you want.” Even in the absence of a formal assignment, the game still allows the player to at least empty Ortega’s ashtrays. In moments of emotional distress, labor itself can become a pastime, just another way to fill our empty moments, and distract ourselves from pain. Sometimes, living in this world is just about getting through time, by whatever means possible.

You can achieve anything

Achievements, the extrinsic reward of choice in 2010s-era of game design, are a a divisive thing. Some players and critics berate them as useless noise that detracts from engaging with a game. Others enjoy the sense of community and accomplishment that comes from having them permanently adorn one’s user profile on a given gaming network. The best defense of them is that they can encourage metagaming: they can encourage players to adopt new strategies and goals they wouldn’t have even known existed if an achievement’s description didn’t clue them into that fact.

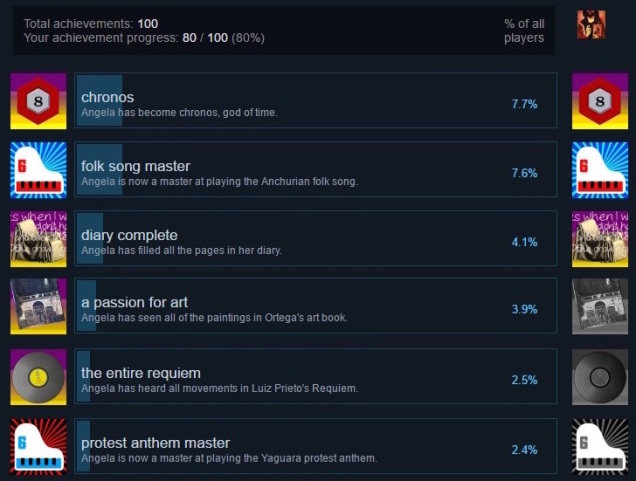

Frankly, I love how Tale of Tales has implemented the achievements in Sunset. They’ve taken something so often associated with “power gaming” and flipped it on its head. Rather than serve as an outlet for players to get competitive against the game’s system (and each other), Sunset‘s achievements encourage players to slow down. The game’s hardest-to-get achievements reward unhurried mindfulness. There’s an achievement for meticulously marking the calendar with the correct date each in-game day. There’s an achievement for remembering to have Angela sit down and write a diary entry every evening, without fail. If you sit down at Ortega’s piano and dutifully practice for a few minute each evening, you’ll master the songs you find sheet music for, and get achievements for that.

There are 100 Steam achievements one can receive while playing Sunset. Some may say that’s excessive. But I can’t quite fault Tale of Tales for using extrinsic reward systems to push players toward carefully exploring the detail of the small world they’ve created. I like that the game cares so much about Ortega’s library that not only are there 41 separate books to peek at, but that you can get 41 separate achievements for successfully seeking out each of these books. In this regard, Sunset falls just behind Jonas and Verena Kyratzes’s Lands of Dream games in my official “games I would recommend to awkward grad students whose favorite activity at parties is to head straight to the bookshelf and quietly geek out” list.

Despite being extrinsic, these achievements can successfully modulate player behavior to further the cause of character building and alignment. Angela is clearly ambivalent about Ortega’s wealth, and frustrated with the fact that her college degree couldn’t prevent her from taking on menial work. The occasional refusal of labor—treating Ortega’s luxurious apartment as a vacation home, rather than a place of work—is clearly in line with her personality, and her politics. The fact that we, as players, are effectively pinned with a little badge each time we sneak in a few minutes for Angela to pop on of Ortega’s LPs on the turntable is a subtle way of encouraging role-play. The extrinsic sense of reward and satisfaction these achievements offer aligns nicely with what is likely Angela’s own desire not to work too hard. (It is worth pointing out that nowhere in the game’s 100 achievements is there an achievement for successfully completing each and every task that Ortega assigns Angela.)

Structuring absence

On January 17, 1973 of Sunset‘s in-game calendar, Angela writes in her journal:

Why am I still taking care of this apartment? Ortega leaves me mundane tasks while a war is brewing outside. A war we’re more deeply involved in than we allow ourselves to believe. But the work is comforting. Rinsing dishes in warm water, ironing clothes, and straightening the place up. It grounds me. Beyond the windows, the spectacle of fire and chaos is not a real existence. Reality is living day to day, tidying up, mending things, and sitting down to write in a journal.

This quote encapsulates so many things that I’ve come back to again and again in my discussion of process genre games: the way in which rituals can be satisfying, the ways in which satisfaction can act as both a replacement for and counterpoint to “fun,” the way in which a truly great process genre game will complicate our satisfaction, denying it at key times or making us consider its price. Between this quote and everything I’ve said about the game so far, one might be tempted to conclude that, yes, Sunset is the preeminent manifestation of the process genre in videogame form.

Except, in all of my descriptions of Sunset so far, I’ve left out something important. Not mentioning it has distorted some of the points I made above, but it seemed right to push acknowledgement of it to the end of the entry, where I would have room to truly consider its implications. The truth is, there’s something really weird going in in Sunset:

You don’t really do work in it.

Now, all of the games I’ve looked at so far use some degree of abstraction in their representations of labor. Cart Life, after all, turns the act of pouring coffee into a typing minigame! But Sunset pushes this abstraction further: work isn’t really represented at all. It is glossed over by temporal ellipses. Tasks are listed in Angela’s to-do list, and players can initiate them by approaching some object in the apartment (cleaning supplies for mopping the floors, shoes that need polished, ingredients for a meal that needs made, etc.). Once there, players have a choice as to how, exactly, they will approach the task. (This choice is usually one between “cold efficiency” and “flirtatious whimsy,” and affects Angela and Ortega’s developing relationship.) All there really is to do, though, is to make that choice. Once the choice is clicked, a set amount of time passes, accompanied by time-lapse like imagery of the city outside Ortega’s apartment. Players are then greeted with a view of the work Angela has completed in their absence, illuminated by a now lower-angled sun.

Certainly, this tactic saved Tale of Tales a tremendous amount of work animating dozens of different tasks. It does, though, have a strange effect on the “process genre” feel of the game. As I’ve mentioned in the opening paragraph of each of these posts, the process genre in cinema is about seeing tasks through to their completion. It encourages us to marvel at the way human tasks can transform raw matter into useful items, can alter a landscape, can bring order to disorder. When you really get down to it, Sunset doesn’t exactly do this. It keeps the labor, but it skips the process.

There are, I think, some benefits to this approach. As I’ve written in previous entries, there’s sometimes a danger that the depictions of labor in process genre films and games can become too satisfying or relaxing, dulling the political impact of these works. If your ultimate goal is to foreground the alienation of labor, it’s probably best to avoid anything that might lull players/viewers into complacency too much.

But it does mean that the game’s balance of labor and leisure is perhaps stranger than I previously made it seem. In my description above, it probably sounded as if Angela’s moments of leisure were “breaks.” They are, for Angela—but not really for the player. In fact, they make up the few things the player sits through in real time, since Angela’s labor is elided by the game’s narration. For Angela, these are pockets of relaxation stolen from her job. For us, they represent the majority of time spent with the game. When Angela is busy, the game flies by for us. It’s only when she’s idle that we really get to do anything.

The game’s focus on empty moments, then, is extremely distilled—more than I probably made it seem above. Bazin praised Umberto D‘s proto-process-genre attempts to buck off cinema’s usual “art of ellipses,” to bravely present us with “the succession of concrete instants of life, no one of which can be said to be more important than another.”[ii] Sunset, by contrast, doesn’t force equivalence on a variety of different moments. Instead, it outright inverts the usual art of ellipses. Things as meagerly interesting as cooking dinner or painting walls—activities that would be the star of the show in a process genre film—are elided, and what we are left with is the quiet moments between housework! We are left with a sort of anti-drama reduction sauce, a bouquet full of interstices.

We are left with slow spatial storytelling.

We are left with time we must bide through.

And Angela’s thoughts.

And a revolution, lapping at the margins. Calling out to us.

Sound familiar?

[i]. Bazin, André. “Umberto D: A Great Work.” In What Is Cinema. Volume 2. Translated by Hugh Gray. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005. Pg 82.

[ii]. Ibid, pg 81.