Are “personal games” a thing, in 2017?

They most certainly were a thing back in 2013, as evinced here, and here, and here. I think the case can be made that they were still a thing in January 2016, when That Dragon, Cancer, one of the most buzzed-about “personal games” in existence, finally released. But are they a thing in 2017?

Signs point to “no.” Not in the sense that people stopped making them—au contraire. What happened was that the floodgates opened. Digital distribution made its way to the masses, in the form of itch.io, and Steam’s post-Greenlight non-exclusivity. Twine went from a footnote in Anna Anthropy’s Rise of the Videogame Zinesters to a designated week in every digital media course offered in North America. People are even making and distributing dreary anti-consumerist Super Mario Maker levels.

So, the games themselves have not abated. But the writing about them, the treatment of them as a definable “scene”: yeah, I think that has gone away. Part of this might be about queasy caution among game journalists, who pointedly remember how a non-existent review of Zoë Quinn’s Depression Quest (2013) sparked Gamergate. But mostly, I think, it’s that there are now just far too many of these games to keep track of, and treat as a coherent thing. Now that seemingly everyone is making games about their deepest and most private anxieties, there is little incentive to build any sort of critical consensus on how to survey the how to survey the zinester scene, who to determine what games are worth checking out (if only to pointedly critique), and which creators should be checked in on every now and then, to see if they’ve done anything interesting.

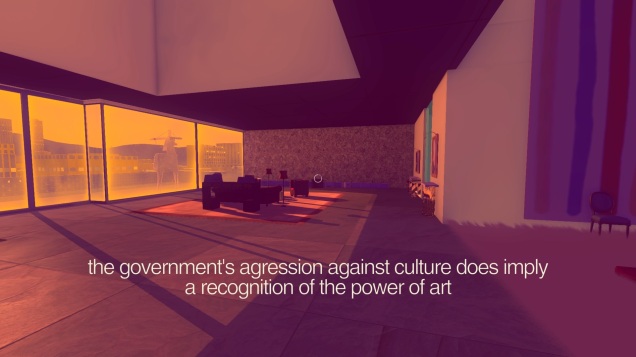

Case in point: in 2013, Will O’Neill released Actual Sunlight. The game became a central text in the conversation around “personal games” movement, and cemented O’Neill as a figure to watch in the interactive fiction/visual novel scene. Fast forward to June of 2017. Will O’Neill (now operating under the moniker WZO Games Inc.) releases Little Red Lie, to absolutely no fanfare whatsoever. It is by sheer chance that it didn’t slip under my radar entirely. As of this writing in November, I have found precious little writing about it anywhere online.

Which is a shame, because Little Red Lie deserves to be talked about. So I’m going to do my own part.