Ian here—

Two weeks ago, I taught Gone Home (The Fullbright Company, 2013) for my “Frames, Claims and Videogames” course. I hadn’t played the game in quite some time, so, in the run-up to the course, I re-played it, searching through the house exhaustively, reminding myself of where every last note and prop was, re-acquainting myself with the ins and outs of everyone’s story. Taking some notes, it occurred to me that it would be nice if there was a guide to it online. Not just a guide to picking up all of the items that give you achievements, or something like that—there are plenty of those online, already. Rather, a guide to the stories Gone Home tells, and where exactly you can find the environmental elements that move those stories forward, and flesh it out.

Well, I guess it falls to me to create what I’m looking for. Again.

My guide to Liz Ryerson’s Problem Attic (2013) was just a walkthrough. This is a bit more, as I have specifically designed it to aid in things like class prep and analysis. It isn’t, by itself, analysis, but tends closer to that direction than the Problem Attic one does. (I’d place it roughly in the realm of my Virginia videos.) Enjoy!

Fabula and Syuzhet

Not surprisingly, most embedded narratives, at present, take the form of detective or conspiracy stories, since these genres help to motivate the player’s active examination of clues and exploration of spaces and provide a rationale for our efforts to reconstruct the narrative of past events. Yet, as the preceding examples suggest, melodrama provides another—and as yet largely unexplored—model for how an embedded story might work as we read letters and diaries, snoop around in bedroom drawers and closets, in search of secrets that might shed light on the relationships between characters.[i]

With these words, Henry Jenkins cements his 2004 essay “Game Design as Narrative Architecture” as the most glaringly obvious choice of course reading to pair with Gone Home. Gone Home does, in fact, take strong cues from literary genres such as melodrama and gothic fiction, in which character’s emotions are charted out in terms of architecture, with unspoken romantic relationships sometimes literally hiding in the walls. This essay is a no-brainer to pair with Gone Home, so of course I did it in my course.

Beyond Jenkins, though, there’s another bit of literary theory that can be useful when thinking through Gone Home: the Russian Formalist’s distinction between fabula and syuzhet. I didn’t assign any formalist criticism to my students for this particular class, but I would consider doing it in the future, and I’m going to use these terms to talk some about Gone Home‘s design here.

As proposed by Yury Tynyanov, the distinction between fabula and syuzhet is the distinction between what we might call story, and how that story is plotted. That is: the fabula consists of the in-universe events that transpired, arranged in the proper chronological order in which they transpired. The syuzhet, by contrast, are those events in the order that we, as readers/viewers/listeners/whatever of the story, are made privy to them. Being a masterful storyteller is often a matter of knowing when to hold off on revealing details of what happened to characters in the past. Jane Eyre just wouldn’t be the same if it began, “Once upon a time there was a man named Edward Rochester, who, upon marrying Bertha Mason, found that her mental health was quickly deteriorating….” Jane’s discovery of Bertha, and of Rochester’s secret, is key to that novel’s air of gothic mystery.

If we consider the careful curation of the syuzhet to be, in essence, the real art of storytelling, than Gone Home‘s environmental storytelling is a curious beast. Although the game is linear in some respects, with certain areas of the house not unlocking until we have found specific items in other areas, within this linearity it does offer a large amount of freedom for players to wander around and pick up items in any order. Much like HER STORY (Sam Barlow, 2015), this creates a lot of potential variability across players’ possible syuzhets.

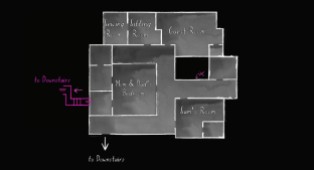

My creation of this guide involves plotting a specific path through the game’s mansion, which in turn involves proposing one specific syuzhet out of many. I’ve broken my guide below into multiple sections, but all of them presuppose a path through the mansion that proceeds as follows:

- Front porch

- Foyer

- Hallway & closet of first floor west wing

- TV room & its closet

- Terry’s office

- Library

- Music room & its closet

- First floor west wing hallway dead end, at the locked basement door

- Up the grand staircase to the second floor and its landing

- Sam’s room and its closet

- Bathroom across from Sam’s room

- Jan and Terry’s room, its closet, and its bathroom

- Guest room

- Sitting room

- Sewing room, picking up the first secret passage map

- Jan and Terry’s room closet to library secret passage

- “Treasure hunting” in the library

- “Treasure hunting” in the east wing hallway

- “Treasure hunting” in the hallway across from Sam’s room

- Sam’s locker

- Basement entrance room

- Basement storage room

- Servant’s quarters

- Junk room

- Sam and Lonnie’s hidden zine-manufacturing room

- First floor east wing main hallway and closet

- Dining room

- Kitchen

- Garage annex

- Garage

- East wing bathroom

- Laundry room

- Green house

- Hidden room under the grand staircase

- Attic

For reference, here are some in-game maps:

Some notes on why this is my preferred path through the game’s space:

- The game gives players a large amount of spatial freedom at the beginning, and it is perfectly possible to explore the second floor before the first floor west wing. I would venture, though, that the imposing staircase and the way the lighting works makes the first floor the more attractive option. I haven’t watched enough people play through the game to know what the actual breakdown is of player behavior, but my suspicion is that the game was designed to subtly encourage exploration of the ground floor first.

- Looking only at the map, it might seem to make more sense to explore Terry’s office before the TV room. The sound of the severe weather warning, though, combined with the glow of the TV, provide subtle attention-grabbing cues that are likely to funnel players in there first, I think.

- This path has the effect of making the player’s syuzhet path almost exactly match the fabula order of Sam’s diary entries, with a couple small exceptions. (Her April 5th and April 10th journal entries are flopped, as are her May 1st and May 19th journal entries.) Since Sam’s story proceeds quite well when it is delivered in this order, I am predisposed to think of this path as Fullbright’s intended player path through the mansion, allowing for some minor variations.

On a final note, if you’re interested in an exhaustive attempt to reconstruct the fabula of Gone Home, you’re looking in the wrong place. My guide cannot hold a candle to this one, by Steam community member Saraneth. Seriously, check it out. It’s awesome, and potentially very useful if you want to study the game further.

How this guide is organized

First, a gripe, and an apology: WordPress’s “slideshow” feature is useless. I would love for you to be able to take it full-screen, to closely examine each of these items, but it doesn’t work that way. In fact, if you want to offer a genuine full-screen slideshow to readers, you are much better off embedding a mosaic.

So, that’s what I’ve done. Please treat the mosaics below as slideshows. Click on the top leftmost image to make it go full-screen, and tap through from there. I’ve kept each screenshot in its full 1080×1920 resolution. Pretty much all of them have extensive captions, guiding you through each of the game’s stories. I have also embedded a little mini-map embedded in each image, letting you know exactly where you can find each item.

To prevent excessive scrolling when trying to find a particular portion of the guide, you can use the table of contents below. Its links will jump you to a specific part of the page.

- The stories: The Greenbrier family, and their house

- The stories: Sam and Lonnie

- The stories: Terry’s writing career

- The stories: Jan’s affair-that-wasn’t

- The stories: Oscar and Terry

- The stories: Katie’s Europe trip

The stories: The Greenbrier family, and their house

Gone Home hooks us in with some immediate questions. Who are we? Apparently we are the ones who have “gone home,” as the title implies. The answering machine message that opens the game indicates that we’re coming home from a trip to Europe. But what are we coming home to? Is our character supposed to recognize this enormous house? And, most importantly, where is everyone? What happened here?

In this first part, I’ll just be walking through the immediate answers to those questions. A lot of things quickly referred to here are expanded in sections below.

1. The title card over black that opens the game pins the time at 1:15 AM on June 7, 1995. Glancing down at the luggage tag on the luggage right next to where we have initially spawned, we are indeed Kaitlin Greenbriar. We boarded a flight on June 6th, and are arriving on this front porch in the early morning hours of June 7th.

![Gone_Home_basic_02 2. Greeting us is a locked door with a cryptic note on it, from “Sam.” “Katie,” it says, “I’m sorry I can’t be there to see you, but it is impossible. Please, please don’t go digging around trying to find out where I am. I don’t want anyone [changed from an earlier “Mom and Dad”] to know. We’ll see each other again some day. Don’t be worried. I love you. —Sam.” Rooting around in the cupboard out here on the porch will reveal the Christmas Duck, beneath which is the key to this door.](https://intermittentmechanism.files.wordpress.com/2017/04/gone_home_basic_02.jpg?w=314&resize=314%2C314&h=314#038;h=314&crop=1)

2. Greeting us is a locked door with a cryptic note on it, from “Sam.” “Katie,” it says, “I’m sorry I can’t be there to see you, but it is impossible. Please, please don’t go digging around trying to find out where I am. I don’t want anyone [changed from an earlier “Mom and Dad”] to know. We’ll see each other again some day. Don’t be worried. I love you. —Sam.” Rooting around in the cupboard out here on the porch will reveal the Christmas Duck, beneath which is the key to this door.

3. Immediately inside and to the left, we find a manila folder with an invoice from a moving company in it. Apparently the Breenbriar family moved into this house on August 1, 1994, about ten months ago. Picking up this invoice prompts Sam’s August 20, 1994 journal entry, “At the New House.”

4. Just who is Sam, anyway? A card that’ has fallen behind a chest of drawers to the right of the main entrance provides a clue: well-wishes for Sam’s recent (?) 17th birthday.

5. In the closet right next to this chest of drawers is a jacket for Goodfellow High School. This could be Sam’s. It could also be Katie’s, though—we don’t yet know our own age.

6. A few feet away is a cabinet with some keepsakes on it. The green skull is a detail in Sam’s story, but via text Katie identifies the trophies as hers. From April 21, 1990, and it’s now June 1995. Assuming these are from high school, there’s no way Katie can still be in high school. She must be, at the very least, in college, or perhaps recently graduated. So Sam must be the one attending Goodfellow High School.

7. We can piece together some important information if we peek into the top drawer in another chest of drawers, on the left side of the grand staircase. It’s some airline details, which place Katie’s original departure for her Europe trip on July 6, 1994. She’s been galavanting around Europe for 11 months, which means that she hasn’t been to the house since her family has moved in. This confirms for us that our character has no extra knowledge about this house that we don’t. She’s exploring it for the first time, just as we are.

8. The answering machine nearby plays Katie’s own message (which we’ve already heard), and two more messages for Sam, from an unknown young woman. The woman just sounds bored in the first message, but in the second one she sounds panicky. Worrying.

9. Above the answering machine, we get our full cast: eldest daughter Katie, younger daughter Sam, mom Jan, and dad Terry.

10. Next to the answering machine is a note from Jan to Sam, telling her to call back a certain Daniel. Sam describes Daniel as a “TOTAL WEIRDO.” Will this person be relevant to our story?

11. Moving into the hallway of the house’s west wing, in a closet we find a note to new students jutting out of Sam’s backpack. The note itself doesn’t tell us much, but picking it up prompts Sam’s September 6, 1994 journal entry, “First Day of School.” The journal entry tells of how the mansion that the family has moved into is known by local kids as the “Psycho House.”

12. Following the sound of a severe storm warning, we’ll find ourselves in the TV room, with a TV that is the source of the broadcast. The dangling RCA cables beneath this TV indicate that the VCR has recently been removed. (Actually, if we check around, we discover that it’s not a VRC, but a fancy Laserdisc/CD player. See Terry’s story for more on that.) Has this house been burgled?

13. Picking up the copy of the awesomely-titled Making Friends, Even If You’re Shy, so embarrassingly recommended to Sam by her dad, prompts Sam’s September 13, 1994 journal entry, “Big Gold Star.”

13. In it, Sam discusses noticing a girl named Lonnie who she thinks is cool. This may seem like an incidental detail, but it’s actually the beginning of the main thrust of Sam’s story.

14. Someone has build a couch cushion fort in here, with a copy of a book called Hauntings & Poltergeists stashed in it.

14. Is this mansion … haunted? The lights do tend to flicker.

15. Across the hall from the TV room, in a manila folder on the top drawer of a cabinet in Terry’s office, we find a non-supernatural explanation for the house’s lighting problems: it has some wiring issues, according to an electrical inspector’s form.

16. If we move through Terry’s office into the library, we can find a book on one of the shelves about dealing with teenagers.

16. Apparently Sam’s parents are having some problems.

17. Exiting the library and Terry’s office, we can find, crumpled in a trashcan, a rather cruel note to Sam from another student. Apparently her reputation as the “Psycho House Girl” carries with it a considerable burden. (By this point, if we’ve been keeping up with Oscar and Terry’s story in the library and office, we’ll know definitively that the “psycho” in question is Terry’s late uncle Oscar, from whom Terry inherited this mansion.)

18. In the music room, in a folder on an end table next to a chair, we find evidence that Sam is perhaps a bit too cool for school.

18. She’s used a boring Sex Ed assignment as an excuse to write an elaborate novella about lost love in the WWII Polish Resistance.

18. Her teacher, apparently, is not appreciative of Sam using this assignment as a creative outlet.

19. More about this “total weirdo” Daniel kid tucked into a pocket in the music room’s closet.

19. Picking up this note will prompt Sam’s September 15, 1994 journal entry, “Default Friends,” about how one’s awareness of their social life changes upon moving.

20. At the end of the hall, we find that the door to the basement is locked. We won’t be able to access it until later in the game. There are a few cryptic notes around here. First, on top of a chest of drawers, Sam has left a note apologizing about “the stuff that’s missing.” Is there more stuff that’s missing, besides the deck in the TV room? What other stuff was taken? And does this note implies that Sam, herself, took this stuff?

21. Crumpled in a trashcan nearby, we see an earlier draft of the note that Sam pinned to the front door. “Katie,” this one reads, “Please, whatever you’ve found, don’t tell Mom and Dad. The attic….” Hmm. The note she ultimately went with simply asked us not to poke around and find anything. This one assumes that we’ll have found … something. Something in the attic, maybe? What’s in the attic?

22. That’s it for the west wing of the first floor, so let’s head upstairs. First stop: Sam’s room, where maybe some of these questions will be answered. On a cork board outside her door, Sam has posted a “strongly-worded letter” to her parents, complaining about not being allowed into the city. In it, she specifies Katie as being three years older than her. If we assume that the Sam’s 17th birthday card is recent, this would put Katie at age 20. Probably in college.

23. Also on the cork board, surrounded by reminders from Jan to call Daniel back because he wants his Street Fighter II cartridge returned, is one of my favorite notes in the game, in Terry’s handwriting: “Sam: Stop leaving every damn light in the house on! You’re as bad as your sister!” If players are anything like me, they’ll have been turning on, and leaving on, every game in the house to alleviate the game’s oppressive darkness, so this is a fantastic joke establishing that behavior (which the design of the game itself encourages) to be in-character for your player-character.

24. Beneath the TV in Sam’s room, another set of dangling RCA cables. Given the large amount of SNES cartridges we see littered around here, it seems likely that the SNES is what is missing here. Who took all this stuff? Was it in fact Sam?

25. In Sam’s closet, we see a plaque laying out what each of the letters in her name “stands for.” I point this out only because we’ll later see one for Katie, and this section is where I’m dumping the details on the relationship between the sisters.

26. Over at Sam’s bed, a nice moment that reinforces that even though this house is new and unexplored to Katie, the things that populate it are still familiar. Katie briefly can’t remember the name of Sam’s stuffed stegosaurus (“Steggy? Stelly?”), but the name comes to her once she checks the tag (“It’s Steggy”). The changing text descriptions here are a nice way of building Katie up as her own character, independent of our control.

27. Under the bed, another indication that, however smart Sam might be (as evinced by her creative writing), she does have something of an attitude problem in the courses that don’t stimulate her creative impulse.

28. Luckily, though, some teachers recognize Sam’s potential.

28. Pulling a pamphlet from Sam’s desk, we can see that a certain Mrs. Blaclock has recommended a creative writing summer program at Reed College to her.

29. Sam apparently likes fine art, based on her poster from a John Everett Millais exhibition. This specific painting, though, brings up some troubling associations, of adolescent women losing their way and being driven to suicide. (This particular painting adorned the cover of the 1994 first addition of Mary Pipher’s Reviving Ophelia: Saving the Selves of Adolescent Girls.)

30. In the bathroom, a jump scare: is that blood splattered on the tub? No, it’s hair dye. Picking up the bottle prompts Sam’s October 22, 1994 journal entry, “Dealing with Roots.” She and Lonnie sure seem close…

31. In Jan and Terry’s room, another missing VCR. Just how many VCRs does this house have, anyway? (A lot. Terry’s job explains this.)

32. Not taken, though, is Jan’s purse. If this house was actually broken into by a burglar, one would think that things like purses would have been taken. This leads credence to the idea that it was, indeed, Sam who carted off all of these electronics. But why? To what end?

33. There are several board games hidden in the closets of this game, some of the little detail that add flavor to the Greenbriar’s lives.

33. I’m specifically including this one here only because it contributes to the overriding theme that this mansion might possibly be haunted, which picks up speed across the next couple of environmental details.

24. Tucked beneath the door of the guest room is a note from Sam, saying that Katie is to use this room while she’s home. It’s filled with boxes of Katie’s stuff, so that makes sense. A worrisome detail, though, is the last paragraph: “You can use my room if you want. I won’t be needing it anymore.” What does that mean? Foreboding shades of Ophelia, again.

25. On a small circular table next to the bed in the guest room, we find a composition book that Sam has turned into a “ghost sighting journal.”

25. Apparently, she and Lonnie are tracking the ghost of the house’s previous inhabitant, Uncle Oscar.

25. Hmm, based on the sightings listed here, Lonnie seems to spend a lot of time in this house.

26. This hall ends in a dead end, lit spookily in red.

26. A sign gives an explanation: the attic houses Sam’s darkroom, and we’re instructed not to enter if the red lights are on. But wait, does that mean that Sam is up there? Why hasn’t she come down? Why did her note on the front door say that it would be impossible for her to meet us when we got home? These details are unsettling. For now, the attic is locked, so we can leave this creepy corner.

37. The last room to hit up on the second floor is the sewing room. In a folder here, we find a note from Sam to Lonnie, one that unlocks previously gated areas of the house, and lets us progress. Sam mentions a secret passage. It gets added to our map.

38. If we return to the closet in Jan and Terry’s room …

38. We now get a prompt that lets us open a false wall.

39. The secret passage just leads to the library, so nowhere we haven’t been before. In it, though, we find another map, noting three hidden compartments behind wood paneling in the mansions’ walls. Time for a treasure hunt!

40. It’s easiest to hit up the one in the library first. There’s nothing in this one that unlocks any of the mansion’s other secrets, but when we pick up this Missfits show flyer, we do prompt Sam’s October 29, 1994 journal entry, “Adjusting to the Dark.” The journal entries we are unlocking in these hidden areas are different than the other ones: they seem to be building to an intimacy between Sam and Lonnie that was only vaguely hinted at in the previous journal entries.

41. Next up, the hidden compartment in the west wing hallway. There’s half of a combination here, to the locker in Sam’s room. There’s also a short story by Sam, but I’ll save that for the section specifically devoted to Sam’s story.

42. Our final hidden compartment is on the second floor, across from Sam’s room. In it, we find a Ouija board …

42. … the remnants of a Ouija session …

42. … and the second half of Sam’s locker combo.

43. Time to unlock the locker.

43. We have the full combination now.

43. Inside, a photo of Lonnie, with her dyed red hair, and the key to the basement. Examining the photo or picking up the key will prompt Sam’s November 1, 1994 journal entry, “There Was Nothing Wrong,” which finally explicitly confirms that Sam and Lonnie’s relationship became romantic. The basement key also unlocks, well, the basement.

43. Some other environmental details in this locker: the telltale security devices on the clothing in here points to Sam doing some shoplifting. There’s definitely some rebelliousness in this one. Now: to the first floor, to open that basement door!

44. In the first room of the basement, we get to peer into a contrast between Katie and Sam. Katie, like Sam, seems smart, but she was much more conformist in high school, applying herself in all the “correct” ways.

45. Ah, the same reproductive system worksheet.

45. With a very compliant response. Check-plus. Night and day, here, between these sisters.

46. Speaking of sisters …

47. Apparently Sam applied to, and got into, that Reed College summer program. Picking this acceptance letter up prompts Sam’s January 12, 1995 journal entry, “Ship Date.” Apparently, June 6th was Lonnie’s ship-out date for ROTC basic training. June 6th … hmm, that’s this past day!

48. The tiny dark room at the end of the hall of the servant’s quarters contains some disturbing implications about Oscar, which I’ll save for Oscar’s story. More relevant to general questions about this house and its history, however, is this scrap of paper. Dated from March 1923, it seems to indicate that the house was used in the trafficking of prohibition-era bootleg liquor. That would go some way in explaining the secret passages.

49. Exiting the basement, we finally gain access to the first floor’s east wing. In the kitchen, a short story concludes the “Daniel” thread of the story.

49. Daniel has turned out to be an extremely minor character in this story, mainly existing to highlight Sam’s changing social constellation.

49. This story is no exception. Picking it up prompts Sam’s May 19, 1995 journal entry, “Daniel,” in which she collapses in grief when contemplating Lonnie’s imminent departure.

50. If you pay close attention to this calendar, we finally get an explanation here as to why Katie’s parents aren’t around, and why it was supposed to be Sam’s responsibility to greet her tonight. Apparently, they are on an anniversary trip. One mystery officially ticked off.

51. This note in the garage provides some redundancy for the information presented on the calendar.

52. But—the plot thickens! If you pay close attention to the dates on this brochure in a filing cabinet in the greenhouse, you discover that the “anniversary trip” is a ruse, and Jan and Terry are actually on a couple’s counseling retreat.

52. (This brochure serves as the capstone for Jan’s story. It’s not super relevant for the general story, though.)

53. In this final corner of the greenhouse, pretty much the furthest spot there is in the game from where we started out, we get one final note of a secret. The night before, Lonnie and Sam apparently celebrated with … something … in a secret room behind the grand staircase. Our map receives its final update.

54. We can now open this panel …

54. … where we find the remnants of a séance held by Sam and Lonnie.

54.

54.

54.

54. The attic key is also in here. The final area of the game has been unlocked. This story is coming to an end. Picking up the key prompts Sam’s June 6, 1995 journal entry “In the Attic.” In it, Sam, writing just earlier today, sounds morose. She says she “just wants to sleep,” and that she going to “go up to the attic … and wait …” Alarm bells are going off right now that this might not be the happiest of endings.

55. Only one way to find out. Up to the attic …

56. Examining a picture by Sam’s sleeping bag, we get some very relieving news, in the form of Sam’s June 6, 1995 journal entry “I Said Yes.” Lonnie couldn’t go through with leaving for basic training, and called up Sam. (That was her voice we heard on the answering machine.) The two of them decided to run away together, with Sam grabbing the unsecured electronics to pawn to provide them with starting funds to start a life together. She’s safe from harm, running away with the love of her life.

57. In the final nook of the attic, we finally get an explanation into how Katie has been privy to these journal entries: Sam actually left her physical journal up here, with instructions that allowed Katie to read it. Clicking on this prompts the end credits for the game.

The stories: Sam and Lonnie

Although the question of why Katie arrives to an empty, ransacked house provides the initial hook for Gone Home, the story of Sam and her girlfriend Lonnie turns out to be very much the central story of the game. It’s the only story that is actually revealed to us in the first-person, through journal entries, rather than through letters and other environmental details. What’s more, these journal entries are actually read out, meaning that Sam is the one character with prominent voice acting in the game (although we do at points hear both Katie’s and Lonnie’s voices).

As a result, this is very much the most overt story of Gone Home, with less needing to be carefully teased out from environmental detail and gradually pieced together. This guide will show you where to find all twenty-three of Lonnie’s audio diaries, her five cassette tapes, three Captain Allegra stories, and also a few incidental environmental details. I won’t be spelling out Sam and Lonnie’s story in the captions as much, though, because it is simply not necessary.

1. Picking up the movers’ invoice prompts Sam’s August 20, 1994 journal entry, “At the New House.”

2. Grabbing this note from Sam’s backpack in the close in the first floor west wing prompts Sam’s September 6, 1994 journal entry, “First Day of School.”

There’s a photo of a girl in a military uniform with pink hair in the drawer of the credenza where we also find Katie’s Paris postcard, and Uncle Oscar’s obituary. Much later in the game, we’ll be able to recognize this as Lonnie.

Entering the TV room, we find the first of what will ultimately be five cassette tapes in the game. Each cassette tape comes with a player near by, so you can pop it in and start listening. (If you see a tape player, that’s a good indication that you should start looking for a cassette tape, as well.) Unlike Heavens to Betsy and Bratmobile, Girlscout is not a real Riot Grrrl band. It is Lonnie’s fictional in-universe band.

3. Picking up the copy of Making Friends, Even When You’re Shy by the TV prompts Sam’s September 13, 1994 journal entry, “Big Gold Star.”

![Gone_Home_Sam's_Captain_Allegra_story_01-1 In the TV room closet, next to the television, we can find stuffed in a box Sam's story "The Hevin [sic] at the Edge of the World," the first in a series of continuing adventures of Captain Allegra and her first mate.](https://intermittentmechanism.files.wordpress.com/2017/04/gone_home_sams_captain_allegra_story_01-1.jpg?w=208&resize=208%2C208&h=208#038;h=208&crop=1)

In the TV room closet, next to the television, we can find stuffed in a box Sam’s story “The Hevin [sic] at the Edge of the World,” the first in a series of continuing adventures of Captain Allegra and her first mate.

We might find this story to be charming, but her teacher thought otherwise. Well-hidden in the shadow next to this box, we can find a note to Sam’s parents, warning them that some details of Sam’s story strike the teacher as possible signs of gender non-conformance.

4. Grabbing the letter from out of the jacket pocket in the music room closet prompts Sam’s September 15, 1994 journal entry, “Default Friends.”

4. Part two of the “Default Friends” note.

5. Picking this note out of the bottom drawer of the chest of drawers near the locked basement door prompts Sam’s October 4, 1993 journal entry, “Best Laid Plans.”

6. Climbing the stairs to the second floor, we find just an empty case with no cassette tape in it, under a bookshelf. Picking this up prompts Sam’s October 4, 1994 journal entry, “Hanging out with Girls.”

Surprisingly, there are no journal entries to be prompted the first time we enter Sam’s room, but there is plenty of environmental detail. First up, the second cassette tape, Bratmobile’s Cool Schmool.

Beneath the TV stand, Sam’s notes on Chun Li moves provide evidence of her training regimen while using Street Fighter II as a way to court Lonnie.

You’ll find “The King’s Labyrinth,” the second part of the ongoing adventures of Captain Allegra and her first mate, in a cupboard in Sam’s closet.

Under a pile of pillows on Sam’s floor, we find what seems to be one of the earlier note-based correspondences between her and Lonnie.

Tucked under Sam’s bed is a note about constructing a motorcycle, presumably from Lonnie.

In the trashcan next to her desk, Sam somehow got her hands on a disciplinary report filed against Lonnie at school.

Immediately outside the door of Sam’s bedroom that leads toward the bathroom, tucked under her backpack, we see a note about how Todd is insisting she and Lonnie go see Pulp Fiction.

7. Picking up the bottle of hair dye in the bathroom prompts Sam’s October 22, 1994 journal entry, “Dealing with Roots.”

Also in here, we can see that Sam used a label gun to affix the message “Lonnie rules” inside the medicine cabinet.

Along with the ghost sighting journal (which I included in the previous section of the guide), the guest room also houses this note from Lonnie to Sam, explaining various ROTC flags.

The third cassette, Heavens to Betsy’ Nothing to Stop Me, is on a chair in the sitting room, where Jan’s painting stuff is set up.

8. In the top drawer of a dresser here, we can find a note that prompts Sam’s first October 29, 1994 journal entry, “Lie-to-Mom-and-Dad Situation.”

We need to go into the sewing room to unlock the next section of the game, and while we’re here we might as well check out some other details. First, the case of a dub Lonnie made Sam of Heavens to Betsy’s album Calculated.

In the wardrobe in the corner of the sewing room, we see that Lonnie drew up some plans for some pretty elaborate Halloween costumes, based on Sam’s Captain Allegra and First Mate characters. Hmm, Lonnie is wearing the First Mate costume. That seems genderbent. Isn’t the First Mate typically portrayed as a man in Sam’s stories?

Those aren’t just plans: Lonnie actually followed through with them. She seems to be rather skilled with a sewing machine!

9. Following the “treasure map” of hidden compartments that we find in the first secret passage, we can pry open a loose panel to find this flyer for the Miss-fits show Sam and Lonnie went to. Picking it up prompts Sam’s second October 29, 1994 journal entry, “Adjusting to the Dark,” which begins to make it clear that Sam and Lonnie’s relationship is romantically intimate.

In our second stop on the treasure hunt, along with the second half of Sam’s locker combination, we find “The Green Glacier,” the third and final episode in the adventures of Captain Allegra. It’s marked as “private,” and hidden here in a secret compartment.

In it, the Allegra’s First Mate undergoes a gender transition into a woman.

10. Picking up either the photo of Lonnie or the key to the basement in Sam’s locker prompts Sam’s November 1, 1994 journal entry, “There Was Nothing Wrong.” This finally spells out the scope of her relationship with Lonnie, as it details their first kiss.

Sam also has a copy of “Gentleman” magazine stashed in this locker. Katie’s reaction to it, “Gosh, Sam,” is exactly the same as her reaction to finder her father’s stash, presumably earlier.

Moving now into the basement, the first easy-to-grab item is a note on a circular table near the wardrobe in the corner of the first room.

It details a charming back-and-forth between Sam and Lonnie about their Thanksgiving plans.

11. Nearby, picking up this picture of an “S+L” heart prompts Sam’s December 8, 1994 journal entry, “It’s Different Now.”

12. In the storage room, picking up Sam’s acceptance letter to the Reed College summer program in creative writing prompts Sam’s January 12, 1995 journal entry, “ship date.”

This is well hidden, but if you look across from the Reed College letter, poking around in the dark in the storage room, you can find a trunk that you can open. Do so, and there’s a catalogue listing for a breakable heart necklace that Sam has noticed.

The fourth cassette, another Girlscout track, hides in waiting in the corner of the servant’s quarters, near the radiator.

A tape player where you can play this cassette is on a nearby table. Jutting out from its shelf is a letter from Lonnie to Sam.

Apparently Lonnie spent Christmas break with some family in Mexico.

This is an interesting bit: well hidden on the floor, between this table and the trash bin, there’s a paper in which Sam describes a sexual experience with Lonnie. After a few seconds of holding it, Katie will realize what it is, and put it down, giving Sam her privacy. Further attempts by the player to click on it will result in Katie refusing to pick it back up. An interesting moment of having a character assert herself in the UI.

13. The Girlscout setlist on the nearby wall prompts Sam’s February 11, 1995 journal entry “I Can Sing”

14. On a table in the junk room, this postcard prompts Sam’s March 11, 1995 journal entry, “Stick with the Group.”

14. Lonnie’s text here made me laugh aloud.

Sam and Lonnie’s hidden zine-making room has a bunch of stuff to look at, including this scattering of notes by the green lamp.

What these scraps are is unclear. Oddly, this one is a snippet of a journal entry we’ve already heard.

The others aren’t, though. Maybe these are portions of another, larger journal?

15. Picking up this letter, a reply to what was apparently a letter from Sam to the school principle Mr. Grossman asking for Lonnie not to be disciplined, prompts Sam’s April 10, 1995 journal entry “Getting Lonnie.”

Around this room, we can find the raw materials used to create the imagery for Sam and Lonnie’s zine.

The fifth cassette. Heavens to Betsy this time.

More zine raw materials.

Still more zine raw materials.

The zine itself.

In this note, found in a folder on an endtable in a couch nook as you come through the passage into the first floor’s east wing, sketches out Sam’s and Lonnie’s respective relationships with their mothers.

16. If you close that folder, you reveal this heartbreaking scrap. Picking it up prompts Sam’s April 5, 1995 journal entry, “The Nunnery.” (If you follow along

In the closet next to the dining room, you can find a package where Lonnie left a note for a skull she got Sam from Mexico.

In case you missed that skull, it’s just behind you, in the foyer, next to Katie’s track trophies.

17. A disciplinary referral and a note from Sam’s parents.

17. One of these (I’m not entirely sure which one) prompts Sam’s April 22, 1995 journal entry, “A Very Long Phase.”

Our sixth and final cassette tape, one more Bratmobile track, can be found in the drawer on a small table holding a tape deck.

A note on the fridge reveals that Sam has a high school job at the Clown Burger. Perhaps some savings from this are helping further support her and Lonnie when they run away?

18. This three-page letter on the kitchen table prompts Sam’s May 19, 1995 journal entry, “Daniel.”

18.

18.

19. Picking up this hat hanging on the handlebars of the bike in the garage prompts Sam’s May 5, 1995 journal entry, “Just Gone.”

A name tag in the trash bin in the garage gives us more evidence of Sam’s job.

This crumpled-up piece of paper chronicles Sam and Lonnie’s plan-making for her last day in town … including some unmentionable plans.

20. Before we hit up the greenhouse, we should take a detour to the dead end in the hall here. In it there’s a hidden compartment, with the paneling already pulled away. Picking up the Girlscout show flyer inside will prompt Sam’s June 3, 1995 journal entry, “Dedication.”

21. In the greenhouse, picking up this map to open the final secret passage of the game prompts Sam’s June 5, 1995 journal entry, “Life Moves On.”

22. Picking up the key to the attic prompts Sam’s first June 6, 1995 journal entry, “In the Attic.”

22. Picking up the drawing of the broken “S+L” heart necklace prompts Sam’s second June 6, 1995 journal entry, “I Said Yes.” This is the final Sam journal entry in the game.

Before you click on Sam’s journal at the end of the attic to conclude the game, you can look at some of her and Lonnie’s photos.

Very high school.

Aww, they did buy the necklace!

The stories: Terry’s writing career

Terry’s side story is anchored by some fun props—his books, in particular, with their pulpy JFK conspiracy sci-fi alternate history nonsense subject matter. As such, it is probably the most attention grabbing of the side-stories in Gone Home. Terry’s story takes on some extra resonance when we combine it with Oscar’s story, but in this section I will just be outlining the basics of Terry’s career arc.

1. Peeking in the cabinet next to the toilet in the bathroom right by the front door, we find an issue of Author Magazine. Apparently, someone in this family is an author, or at least considers themself one.

2. Next up, the TV room. Here, if we check out some things on a table next to the TV, we see that Terry gets high-quality VRC equipment shipped to his house …

2. … apparently because he reviews them for a consumer magazine.

3. In the bookshelf in the corner of this room, we see the first evidence that Terry is a published author.

3. His name is attached to a book entitled The Accidental Savior.

3. Apparently, the electronics magazine reviewing job is a day job, a gig to pick up a regular cash flow.

4. Lots of detail in Terry’s office. In his typewriter, evidence of him doing his day job, reviewing a dual CD/Laserdisc player.

5. Elsewhere around his desk, though, there is plenty of evidence of novel-writing as well. From what we see of his notes, Terry’s novels are weird science fiction alternate histories that flirt with JFK conspiracy theories.

6. A few crumpled pages next to the desk.

6. Apparently, Terry didn’t consider this to be good enough.

6. (Is this what the “you can do better” on the cork board refers to?)

7. On the chair is apparently what counts as research in Terry’s writing process.

7.

8. Tucked in a corner of Terry’s bookshelf, we see the writer’s best friend peeking out.

9. If we poke around in the cuppord at the bottom of a booksheft in the adjacent library, we find a box of unsold copies of The Accidental Pariah, Terry’s second book, and apparently a sequel to The Accidental Savior. (So the book he’s working on now is the third in the series?)

9. If you pick up enough copies, you’ll reveal that Terry’s hiding a gentleman’s magazine in this box.

9. This 1) weirds Kaitlin out, and 2) sets up an echo when she discovers another issue of this magazine in Sam’s room.

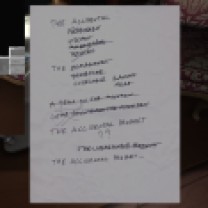

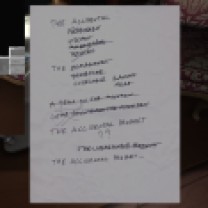

10. Turning around, poking out from under a newspaper, we find a scrap of paper on which Terry has scribbled mulpiple possible titles for his comeback novel.

11. In another corner of the library, we find a stern letter to Terry from his editor at the magazine. Apparently, Terry’s reviews went through a period of getting really weird, including tangents about his childhood. The letter is dated November 1, 1994, and the editor says Terry’s reviews had been off the “last few months.” Terry and his family moved into the mansion on August 1, 1994. Is that what prompted this? What’s going on with Terry? test

12. Behind the bar in the music room, we find another copy of The Accidental Pariah.

12. If Terry has two novels under his belt, why does he need this day job, anyway?

12. The answer comes in the form of a letter from the Mercury Books, Terry’s former publisher. Apparently, the “Accidental” series always sold poorly, and they dropped him … back in 1976. That’s nearly twenty years ago—just a few years after Katie was born. Terry’s been out of the game for quite awhile, pretty much his daughters’ entire lifetimes. If that’s the case, what has prompted the return to the Accidental series?

13. In the closet in the music room, boxes upon boxes of unsold copies of The Accidental Savior ..

13. … and The Accidental Pariah.

14. That’s it for the west wing of the first floor. Upstairs on the second floor, there’s not much to find relating to Terry at all. The one exception is a business card for Unknown Dimension Literature in the endtable next to his bed. What’s up with that?

15. In the basement storage room, we come across a portrait of Terry’s father, Richard Greenbriar. He was a professor lauriate of English literature—that has to be a tough burden on a son whose forrays into writing are in pulp JFK alternate-history sci-fi. The face of this portrait is cut out. Were Sam and Lonnie having some fun? Or did Terry do this?

15. If we turn around from exactly this spot, Katie will spot one of Richard Greenbriar’s books. It’s on Joyce. Nope, not an easy father to have if you have Terry’s writing interests.

16. In the dark, another copy of The Accidental Savior. Kaitlin notes that it has something attached to it.

15. If we pick it up, we find a letter from Terry’s father, about Terry’s first book. Richard is polite, but clearly disapproving of the subject matter, writing “you can do better” in his final line. (We’ve seen those words before, above Terry’s typewriter. He hasn’t forgotten this letter.) Richard doesn’t come across as an easy man to have as a father: he signs this letter to his son “Richard Greenbriar, PhD.”

17. On a tray in the dining room, we see that Terry actually produced a partially-finished manuscript for the new sequel, titled The Accidental Warrior. Terry apparently crumpled it up, but Jan has rescued it (perhaps from the nearby trash bin?) and written an encouraging note on it.

18. In the room next to the garage, we finally see that there’s some good news in Terry’s life. Unknown Dimension Literature (the business card of which we saw back in the bedroom) is re-publishing Terry’s first two books.

18. What’s more, they reached out to him, unsolicited, to do so.

18. Along with the letter is a copy of the new Unknown Dimension paperback edition of The Accidental Pariah.

18. Whatever Terry’s frustrations, it seem that this good news has perhaps provided the motivation for his return to writing after a twenty-year draught, so that’s something, at least.

19. Our last stop is in the greenhouse, but on our way let’s peak beneath a table in the kitchen corner. The Accidental Savior is here, as well, looking good in its new paperback cover.

20. Both Terry’s and Jan’s side-stories conclude via materials scattered in the greenhouse. In one of its corners, Terry has another writing table set up, with a second typewriter. Apparently, this space has been more productive for him. Copies of both The Accidental Savior and The Accidental Pariah, filled with Post-its, sit on a filing cabinet.

20. Inside the cabinet, we find a manuscript of Terry’s new book, with the new title “The Accidental Human.”

20. A letter next to the typewriter tells us that Terry is pitching this new manuscript to Unknown Dimension.

20. Finally, we see the cover copy for The Accidental Human. It seems like Terry is letting go of his JFK obsession, and the hook for the new book is that series protagonist John Russel having to save his own life, rather than JFK’s.

The stories: Jan’s affair-that-wasn’t

Jan’s side story is somewhat more scattered and spread out than Terry’s, with fewer central props (such as the copies Terry’s books) to cement her development. It involves her career, her flagging social life, and her increasingly strained marriage with Terry. The fact that Terry gets a larger role in Jan’s story that Jan gets in his gives things a lopsided feel: Jan stand apart less as her own agent than Terry does within the Greenbriar family.

1. Our first glimpses into Jan’s life occur right in the foyer. (In fact, it is quite possible for players to encounter her story first.) First up, a map to work, in a chest of drawers immediately right of the entrance. It’s not at all obvious that this is Jan’s at first, but we’ll be able to put together later that it is. What is obvious from the get-go is that this person is annoyed by the length of their new commute.

2. If we continue to our right, toward the closet, we can see Jan’s coat, and the ID on it, which identifies her as a forest ranger.

3. In the drawer of a desk next to the locked door to the house’s first floor east wing, we find a letter from Carol, Jan’s old college roommate who has apparently become her confidant. Carol congraduates Jan on moving into a mansion.

4. One a table in a hallway in the first floor’s east wing, we find a manual for controlled burns. Aparently, as a forest ranger, that’s something Jan does.

5. That’s it for the first floor, for now. Moving upstairs, on a shelf on a table on the landing right at the top of the staircase, we see a local newpaper article that Jan has been mentioned in. Yes, she is involved in controlled burns—including on that started in October of 1994. This is the first time we see the forest where Jan works at named: it’s Flintlock National Forest. If we connect the dots, we can put together that it’s her that was annoyed with her new commute. (The downside of living in this mansion, it seems.)

6. Just a few feet away, we find two more details about Jan’s life. In a drawer in a small endtable, there is some more detail about the controlled burn—another ranger will be joining her for it, apparently. This seems like an utterly banal detail, but it will evolve into something more later.

7. On top of the endtable, there’s a personal calendar for September 1994. Originally, Jan had a packed schedule, with couple’s bowling scheduled on Wednesday evenings, ballroom dancing lessons on Fridays, and cooking classes on Wednesday.

7. By the end of the month, she had dropped out of all but the cooking classes. Hmm. Maybe her schedule was too busy. Also, though … the activities she dropped out of were couple-oriented activities. Was her husband Terry the one who led to her no longer participating in these? Did he lose interest?

8. Next stop, Jan and Terry’s bedroom. A quick glance at the VHS tapes lined up by the TV reveals a very “Mars”/”Venus” taste discrepancy. Based on the handwriting on the lables, it looks like Terry’s tastes lean toward fare such as All the President’s Men, Bridge on the River Kwai and Silence of the Lambs, whereas Jan prefers The Sound of Music and taped episodes of Inside Edition.

9. In a drawer in the endtable next what (presumably) is Jan’s side of the bed, we find another letter from Carol. This confirms the possibility of marital strife. Carol talks about the new ranger assigned to the controlled burn—apparently his name is Rick. (Ranger Rick? Really?) What’s going on between Jan and Rick? Carol comes across like a gossipy schoolgirl in pressing Jan for details.

10. Maybe something is going on between Rick and Jan.

10. He has loaned her his personal copy of Leaves of Grass …

10. … with a personal message scrawled on the bookmark.

11. In Jan and Terry’s bedroom closet, we find an instructional book on watercolor painting. There’s no evidence yet that this is Jan’s, but evidence will accumulate later. (She certainly has taken up a lot of hobbies since the move. A response to newfound isolation?)

12. It’s not that Terry and Jan aren’t trying: a marriage guide sits on the table next to the toilet of their bathroom.

12. “Ugh” is Kaitlin’s response—understandably so, given the book’s focus on “fresh and exciting ideas for the bedroom.” (For an even more visceral reaction on Katie’s part to an awareness of her parents’ sex lives, check out the bottom right drawer of the dresser closest to the dresser to the right of the TV. It’s not directly relevant to Jan’s story, but it’s worth a look, and a laugh.)

13. One last thing to note here, before we leave Jan and Terry’s bedroom. There’s and Earth, Wind & Fire poster on the wall, near the side of the bed that we might expect to be Terry’s (if the other’s is Jan’s). Is Terry an Earth, Wind & Fire fan? Are they both fans?

13. Terry’s musical tastes tend to run toward jazz, if we take the record collection in the music room as evidence.

13. (The fact that we find Terry’s books in the music room seems to mark it as “his” space.) Perhaps it’s just Jan that’s the fan?

14. Someone’s been painting in the sitting room. Given that we find Jan’s stuff dotted about the room, it seems safe to assume that she’s the painter in this house. (That may mean that the many other canvases we see dotted around the house are hers, as well.)

15. On an endtable next to a chair in the sitting room, we see Jan’s official evaluation of Rick as a park service employee. Not only did she give him top marks, but she actually requested his permanent reassignment to Flintlock Forest. Hmm…

16. If we poke around in a box in the sewing room, we find a romance novel. It doesn’t seem to be to Sam or Terry’s tastes …

16. Is this a glimpse into Jan’s fantasies? If so, the implications are pretty clear.

17. There’s not much of Jan’s in the basement, but there is one interesting detail: apparently, she’s Canadian, and got US Citizenship after marrying Terry. It doesn’t move the story forward, per se, but it’s a nice character detail.

cubbyhole here. First, tucked under the couch, a receipt for what can only be described as a makeover.

19. On the other side of the couch, a bit of career detail: Jan was offered a promotion in Februrary of 1995.

20. A little bit down the hall, we can rescue a concert ticket out of the air vent: Earth, Wind & Fire. Sounds like something Jan and/or Terry would like. It’s dated February 23, the day after Jan’s elaborate makeover.

21. There’s a well-hidden detail near the entrance to the dining room. Jan’s purse sits on a table, next to some other clutter.

21. If we pick it up, we find a photocopied forestry manual beneath. Pretty boring stuff, so far.

21. But if we toss the manual out of the way, we see something else still beneath that: a note, from Rick, inviting Jan to the Earth, Wind & Fire concert. Hmm, so Terry was definitely left out of this: it was a purely Rick and Jan ordeal? It seems unlikely that either of them would have considered it a “date” … also according to this note, Rick has a girlfriend. Still, though … given what we can ascertain about Jan’s relationship to Rick, this wouldn’t have been an entirely innocent night out. If nothing else, her elaborate makeover indicates that she was excited for it.

22. In a drawer in a desk on the other wall here, we find another letter from Carol, this time congradulating Jan on the promotion offer. Also, Jan seems to have talked to her about the concert with Rick. Carol cautions Jan about reading too much into their outing (which it seems like Jan was quick to do).

23. Across the hall, in the kitchen, a new detail: Rick’s girlfriend wasn’t just a “girlfriend”: she was a fianceé. Hmm, his note didn’t mention that. Helen Margaret is her name, and Jan has been invited to their wedding. Awkward. This romance doesn’t seem to be going in the direction Jan is fantasizing.

24. Posted near a counter, a letter confirming Jan’s acceptance of the promotion. In it, we learn something the previous letter hadn’t revealed: it involves a transfer away from Flintlock, to the Regional Management Building, closer to her home. Being closer to home certainly has its appeals, as evinced from the very first note of Jan’s that we saw. It took her about two months to accept what should have been a no-brainer promotion. It seems likely that Rick was part of that equation. With him getting married, though …

25. And right nearby a calendar with the date of the marriage: June 4. Hmm, that was just two days ago. Also, it looks like Jan and Terry didn’t make it. They’re on an anniversary trip, which finally explains their absence for Kaitlin’s return.

26. Two rooms over in the garage, redundancy at work: another note confirming that Jan and Terry are on an anniversary trip, which is why they left Sam in charge of greeting Kaitlin when she got back. (Still doesn’t explain Sam’s absence, though…)

27. Finally, the greenhouse. Based on what we find in Terry’s filing cabinet, the “anniversary trip” is a ruse: in actuality, the two of them are going on a couple’s counselling retreat. With Jan crashing back down to reality from her fantasy relationship with Rick, apparently she and Terry have decided to tough it out, and try and patch things up. (The book by the toilet also supports this.)

27. Practicality, it seems, has won out over flirtatious fantasy.

The stories: Oscar and Terry

The story of Oscar Maran and his relationship to his nephew, Terry Greenbriar, is difficult in two respects. First, it is difficult simply because it is the toughest to piece together. Its key documents are among the toughest to find in the game, and even when you have everything in front of you, it still requires some amount of interpretive effort to pin everything down. (It is a far cry from Sam and Lonnie’s story, in this regard.) Fully piecing everything together requires not just reading documents, but also paying close attention to other environmental details, such as objects located in strange places. It is a master class in subtle environmental storytelling.

The other reason that the Oscar-Terry story is difficult is because it is very dark and upsetting. Before you continue on, I should add a content warning for sexual abuse.

Before I offer my own breakdown, I first want to point out the good critical work that has been done by others, piecing these various clues together in a persuasive way. To my knowledge, the first author I know to publicly offer a take on Oscar’s story was Austin Walker. It has since been written about by a bunch of other people. I deserve no credit for laying this out here. All I’ve done is take the screenshots.

1. We are first introduced to Uncle Oscar via his obituary, in a drawer in the credenza where Lonnie’s photograph and Katie’s Paris postcard are also located. At this point, we have no way of knowing his relation to the family. The obituary is oddly contradictory, positing that Oscar was a “well-loved figure at the center of the community,” while also stating that “in the decades preceding his passing he was seldom seen outside his house.”

2. To continue Oscar’s story, our next stop should be the library. Inside the folder that houses the stern letter from Terry’s editor (see Terry’s story), there is also a code. This is the code to the top filing cabinet drawer in the office.

3. Head there, and punch it in.

3. Inside, we find documentation from Oscar’s lawyer. This is Oscar’s will.

3. The will answers a very large lingering question in Gone Home: why the family has suddenly moved into this large mansion. The answer is that Terry was willed it by Oscar.

3.

3.

4. One last detail before we leave Terry’s office. If you hover the cursor on the lefthand drawer of his desk, you’ll get a question mark. This indicates a false bottom. You can remove it.

4. Inside is a letter from Oscar. It’s missing his name, but it has the Arbor Hill address.

4. The letter is ripped, but the last paragraph seems to say that Terry is always welcome at his uncle’s house, although Oscar also says “I will understand of course if you feel you cannot accept the invitation.” Why would Terry feel this way? Was there bad blood between the two? Why would Oscar have willed Terry the house, then?

5. The next time we see a hint of Oscar, it’s in the game’s first secret passageway, connecting the parents’ room with the library, where we find Lonnie and Sam’s “treasure map.” This small cross, with John 3:16 handwritten on it, adorns one of the walls, which are lined with advertisements for women’s clothing. If we pick it up, the lightbulb in the passageway will burst. (Maybe Oscar does haunt this house.) That will make it impossible to see in the passageway, but players can carry it out in the library to more clearly inspect it.

6. The last bits of Oscar’s story arrive in the basement, and that’s where things take a disturbing turn. First, a newspaper clipping that’s very difficult to see, partially tucked under a carpet in the large storage room in the dark. In 1959, Oscar added a soda fountain to his pharmacy. Terry was his first customer. This article describes Oscar as a “well-loved fixture of Main Street,” which is strange, considering that, by the 1990s, he was known as the “psycho” inhabiting the “Psycho House.”

7. Over in the junk room, a ledger for Masan’s Pharmacy. Not too interesting.

8. In the opposite corner, though, something very interesting. In December of 1965, Oscar basically gave the pharmacy away, selling it for a song. Why would he do this? The article doesn’t speculate.

9. We’re going to come back to the basement, but first we need to follow a secret passage upward, to the second floor, where it opens onto the guest room. (Players who had been attentive to the “missing room” on the second floor map will have their curiosity sated with the revelation of this passageway.) As we open the door, a Masan’s Pharmacy receipt tumbles out, with a four-digit code written on it. 1963 … hmm.

10. The code opens this safe, back down in the basement, near the servant’s quarters.

10. Inside is Oscar’s stash of morphine syrettes. Apparently, he was an addict.

10. It also contains a letter to Mary Greenbriar, Terry’s mother. Mary returned it, perhaps without opening it. More evidence of bad blood between family members here. If you squint really hard, you can just barely make out the postage date stamp: it looks like it was sent on February 23, 1973.

10. In the letter, Oscar asks Mary for her forgiveness. (Hmm, 1972-73 really seems to have been when he was trying to re-establish contact with the family.) He acknowledges that he committed a “transgression” years ago, but that he has since “removed himself from all temptation.” What was this transgression that Mary could not forgive him for?

11. If we turn around, we see a height chart, made in Terry’s youth. Terry’s last recorded visit is on Thanksgiving, 1963. Was this when Oscar’s “transgression” became known to Mary? Did she cut ties then? Oscar went through with the mysterious sale of his pharmacy in 1965, two years after 1963, and eight years before his last letter to him. Was this his act of “removing all temptation”? What tempted him at the pharmacy? Was it his access to morphine? Is his addition the transgression?

12. One bit of additional evidence points to something darker. At the end of this hallway, there is a tiny, dark room.

12. If you try to turn the light on in here, Katie will note that it doesn’t work. This room is permanently bathed in darkness.

12. There’s not much in here, but one thing that is in here is a small children’s toy. What went on in this room? And then it dawns: maybe it wasn’t the drugs at the pharmacy that presented the problem for Oscar. Maybe it was the soda fountain. Were CHILDREN the temptation? Did Oscar sexually abuse Terry? Was that the “transgression”? That, indeed, would be unforgivable.

13. As terrible as this supposition is, the truth is that a lot of the elements of Terry’s story click into place once we assume that he was sexually abused by Oscar, in the very house he now lives in. It would explain the lack of focus in his writing, the fact that his VCR reviews are now dotted with “ruminations on his childhood.”

14. It also potentially explains his JFK fixation. JFK was assassinated right around Thanksgiving 1963. Terry has possibly psychologically displaced his own personal trauma onto that national trauma.

15. In this light, Terry’s fathers letter to him on the advent of his first book’s publication takes on a darker undercurrent. When Richard writes that “An author’s work is an externalization of that which he holds dear (and that which he fears),” is he subtly indicating that he recognizes Terry’s novel as a way of indirectly working through his trauma? Is the harsh final note, “you can do better,” actually a veiled proposal that Terry tackle his trauma in a more head-on manner?

16. Despite the hardship we have to go through to get there, this actually makes the ending to Terry’s story happier. His new novel is not just a return to fiction-writing. The fact that John Russell doesn’t need to keep saving JFK’s life anymore, and that he can instead save “his own” life, is perhaps a sign that Terry is gradually moving away from his obsessions, and perhaps finding so psychological peace.

The stories: Katie’s Europe trip

Finally, a series of postcards dotted around the house let us know what Katie was up to this past year, while the family was dealing with its various dramas. I’ve only found four of these, which seems like a small number. Perhaps I’m missing one or two? I’ll update this guide in the future, if I find more.

Our first postcard, from Paris, can be found on top of the credenza in the first floor west wing hallway, where we also find Uncle Oscar’s obituary and the first photograph of Lonnie. (I am forgoing the mini-maps this time around, as I’m assuming that the path through the mansion has been adequately established by now.)

Our second postcard, from London, is sitting on an end table next to Terry’s side of the bed in his and Jan’s bedroom.

Our third postcard, from the Vatican, is on the corner of the dining room table.

Our fourth and final (by my count) postcard is on a small table in the little dead-end nook in the first floor east wing hallway. It’s right next to the crumpled-up flyer that gives us access to Sam’s “Dedication” journal entry.

[i]. Jenkins, Henry. “Game Design as Narrative Architecture.” In First Person: New Media as Story, Performance, and Game. Ed. Noah Wardrip-Fruin and Pat Harrigan. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004. Pg 128.

![Gone_Home_basic_02 2. Greeting us is a locked door with a cryptic note on it, from “Sam.” “Katie,” it says, “I’m sorry I can’t be there to see you, but it is impossible. Please, please don’t go digging around trying to find out where I am. I don’t want anyone [changed from an earlier “Mom and Dad”] to know. We’ll see each other again some day. Don’t be worried. I love you. —Sam.” Rooting around in the cupboard out here on the porch will reveal the Christmas Duck, beneath which is the key to this door.](https://intermittentmechanism.files.wordpress.com/2017/04/gone_home_basic_02.jpg?w=314&resize=314%2C314&h=314#038;h=314&crop=1)

![Gone_Home_Sam's_Captain_Allegra_story_01-1 In the TV room closet, next to the television, we can find stuffed in a box Sam's story "The Hevin [sic] at the Edge of the World," the first in a series of continuing adventures of Captain Allegra and her first mate.](https://intermittentmechanism.files.wordpress.com/2017/04/gone_home_sams_captain_allegra_story_01-1.jpg?w=208&resize=208%2C208&h=208#038;h=208&crop=1)

Hello,

you forgot the pharmacy book in the boiler room from Oscar Masan (in the right corner behind the carton).

Great work!

LikeLike

Thanks for pointing this out! I’m not going to go back and add it (mainly because it would require re-doing all of those little inlaid maps, which would be a huge pain), but at least now its omission has been officially noted in the comments.

LikeLike

Thank you for making this! I’ve just replayed the game, and I wanted more detail about the different documents/objects, and this was exactly the type of summary I needed. Apparently I missed a few objects here and there, so I was fuzzy on Jan and Terry’s stories. This was super helpful!

LikeLike

Thanks! Always happy to see that people are still using this.

LikeLike