It has become a set of dual clichés: in videogames, you either save the princess, or you save the world. Those are the only sets of storytelling stakes offered. The only things that can imbue our actions with importance is to tie our success or failure to the fate of humankind, or the fate of a particular monarchic lineage.

Which is, frankly, alarmingly dumb. By way of contrast, here are some of the resolutions of the great works of cinema: A boy loses respect for his father after the father resorts to thievery. A group of reporters trying to decipher a newspaper tycoon’s last words ponder whether it’s truly possible to know and understand another person. A man and his dying wife are struck by the kindness of their widowed daughter-in-law. The fate of the world does not hang in the balance in any of these scenarios. The stakes in play are emotional, familial, and cultural.

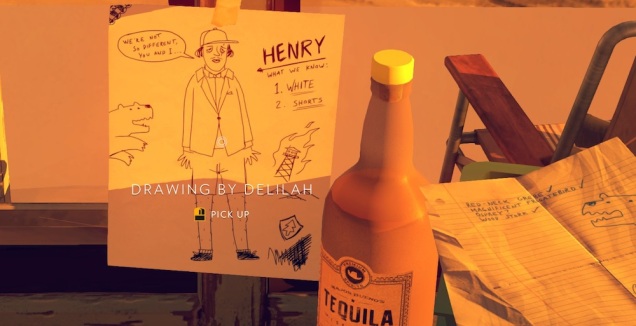

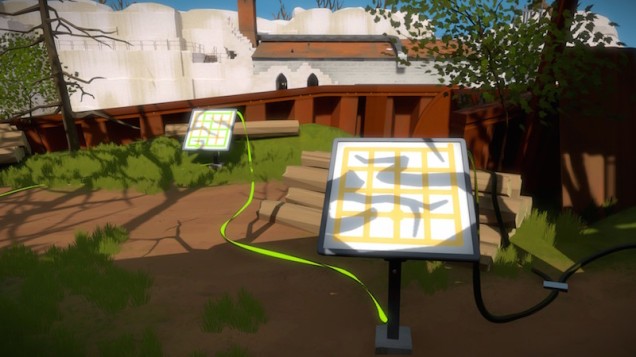

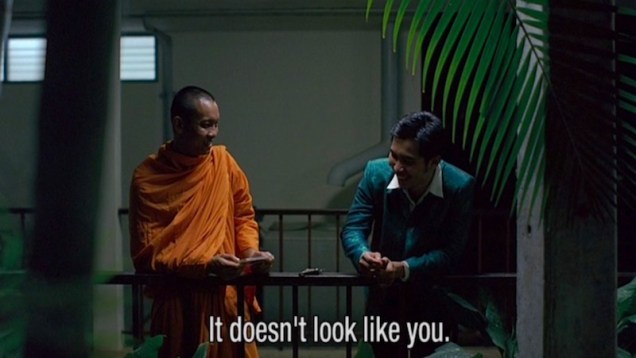

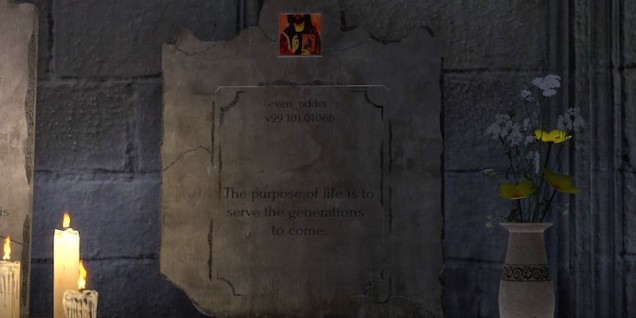

So, whenever a game comes along that gives you a different motivation for caring about its central conflict, that is something to be savored and celebrated. The games listed here all roundly reject tired “save the princess/save the world” narrative stakes. Instead, they offer up goals, character motivations, and resoultions that are more personal, more intimate, or more philosophical. There is, if it can be said, much more at stake in these games than the fate of the world.