Falstaff. Miss Havisham. Anton Chigurh.

Much like yesterday’s category, today’s sub-list is partially a lament that baseline competency in storytelling seemed so long unachievable in games. Defending games as a potential storytelling medium seemed like a silly project, as the games stories had opted to tell just simply weren’t very good. Good stories need good characters. Creating characters as good as the ones listed above, in any medium, is probably an unrealistic goal. But it’s not unrealistic to ask for characters with interesting personalities and motivations.

If I am being perfectly fair, games have historically struggled less with characters than they have with pacing. The 1990s and early 2000s are filled with RPGs and adventure games with memorable characters, even as they might struggle to recount their stories efficiently. In the wake of GLaDOS, though, the ante has been upped. I am happy to report that developers have risen to the challenge. The past decade has been awash in sharply-penned dialogue, superb voice acting, and richly emotional character beats. Here are a few of my highest recommendations.

Oxenfree

Developer: Night School Studio

Released: 2016

Platforms: Windows, Mac, Linux, PlayStation 4, Xbox One, Nintendo Switch

Once upon a time, this space would have been reserved for Heavy Rain (Quantic Dream, 2010), Sony’s gamble on big-budget interactive drama. When it came out, it initially felt like a revelation, a huge step forward in story-driven games. The story in question, though, was a rickety assemblage of hoary genre clichés, lukewarm tripe distinguished mostly by its dishonest narration.

Then the first season Telltale’s episodic adventure The Walking Dead (Telltale Games, 2012) came out, and the torch was passed. No longer did our narrative dreams rest on the misshapen shoulders of Quantic Dream. Telltale’s first Walking Dead foray was as soulful as it was nail-biting, preserving not only the horror of its source material, but also its exploration of intra-personal politics, and philosophical investigation of what it means to be a moral actor after civilization has ended. Intense violence and suspenseful escape scenes were leavened by thoughtful moments of mournful quiet. Telltale seemed to have cracked the code in creating emotionally gripping, long-form serialized narrative in videogame form.

But then Telltale had to go and make ten more adventure game “seasons” in half as many years. They took a stab at just about every licensed property you could imagine: Game of Thrones. Batman. Guardians of the Galaxy. Even Minecraft. Minecraft, of all things! And the more games they churned out, the more their formula shown through. The luster was off, and all we were left with was sandblasted steel boilerplate. The auteur conception of Telltale faded in the shadow of this increasingly gargantuan pile of factory-pressed product.

But that’s fine. It’s fine that the sheen has gone off of Heavy Rain and The Walking Dead. Because, from where we’re standing, it seems that those were just the early glimmers a golden age of narrative-driven adventure games. The main reason those two no longer hold up is that we have now been spoiled with even better games. And that’s never a bad thing, right?

At this particular moment, my vote for the most delightful narrative-driven adventure game sits firmly on the head of Oxenfree. Developed by Night School Studio, founded in part by ex-Telltaler (tale-teller?) Sean Krankel, Oxenfree drops the false-alarm-portentous “X will remember that…” moments of Telltale’s formula, trading them for strong characterizations and a genuinely earned sense of internal stakes. In place of a licensed property, we get an original plot, one that draws heavy cues from 80’s-style “teens discover something dark and mysterious” pop storytelling while remaining distinct enough to be memorable on its own terms. All of this is visually rendered in a gorgeous animation style that recalls Cartoon Saloon’s work, and bathed in a synth-pop soundtrack that veers from syrupy bounces to minor-key echoes on a dime. (A shiny dime, 1986-mint, that spent a summer in the jeans of Mark Mothersbaugh.)

My feelings toward Oxenfree moved through three distinct phases as I was playing. Initially, I simply enjoyed the game. Soon, however, this enjoyment took on a more specific form: the distinct though that this was a videogame I had always wanted to play, but never really known until now. And, finally, I was left with the thought: “Why couldn’t this have been the first videogame I ever played? Truly, I envy those who can enjoy such an impressive piece of craft as their introduction to the medium.”

And for someone interested in games as a storytelling medium, Oxenfree is, indeed, just about the best game I could recommend as an introduction. The only sticking point would be its dialogue system: unlike dialogue wheels of old, it requires some quick timing. Rather than taking one’s time to ponder one’s response to other characters’ dialogue, one must aggressively butt into conversations, making snap decisions. I imagine it might be a bit overwhelming for a newbie, but it turns out to be a necessary feature of the game, allowing it to keep its quips at a snappy, Whedon-esque pace.

And when it works—when everything hums along, and the dialogue maintains a brisk pace—it works so well. These teens are clever, charming, multi-faceted, and voice acted with tremendous panache. Spending time with them peels off layers of characterization for even those who are the least likeable. Alex and her friends are people you’ll want to see survive the night, to close the weird Hellmouth they have accidentally opened, to escape this cursed island. They are quippy and clever, and the time you spend controlling Alex will allow you to feel as if you’re quippy and clever, too.

So Oxenfree receives my highest recommendation. At least until another amazing game comes along and dethrones it. Which, in these exciting times we live in, could happen at any moment.

Firewatch

Developer: Campo Santo

Released: 2016

Platforms: Windows, Mac, Linux, PlayStation 4, Xbox One

“What IS this?”

“WOW! What a MANSION!”

“Captain Wesker, where’s CHRIS?”

“Stop it! DON’T OPEN that DOOR!”

I won’t even bother attributing that above quotations. If you recognize those lines, you can hear them right now, echoing in your head, in all of their deliriously broken glory. The weird syncopated cadence, accents falling on nonsensical syllables. The substitution of sheer volume for actual stress and inflection. The alien pacing, with drawn-out pauses making the whole exchange feel more like a collection of non-sequiturs than it actually is. (If you don’t recognize those lines, I envy you, and I wouldn’t dare sully your ears by making it any easier for you to seek it out.)

In yesterday’s post, I noted that it has been historically easy to beat up on games’ potential as a storytelling medium, since the medium’s output was riddled with so many obvious shortcomings. I gave pacing a lot of weight here, but gross incompetencies in dialogue and voice acting are much more immediately noticeable to the casual observer. Who could blame anyone who didn’t take game storytelling seriously in the mid-to-late 1990s, so few working within the medium seemed to be incapable of writing passable line of dialogue, or competently pronouncing a single sentence of spoken English? Sure, yeah, there was Grim Fandango (LucasArts, 1998). But dialogue and voice acting in this era were much more likely to be defined by the campy malapropisms of Resident Evil (Capcom, 1996), the sleepwalking mumblecore delivery of Shenmue (SEGA AM2, 1999), or the snarling black hole of anti-wit that is Bubsy 3D (Eidetic, 1996).

Will the medium ever be able to disassociate itself from such travesties? Can videogame dialogue-writing and voice acting of the present ever fully wash away the sins of the past?

It is going to take a lot of work, to be sure. But if games keep coming out that are as good as Firewatch on this front, I have faith that it can be done.

There are a lot of generic twists and turns in Firewatch‘s story. It begins as a “man who should know better runs away from his emotional responsibilities” tale, with recognizable roots in some Westerns, as well as Wim Wenders’ road movies. From there, it moves cautiously into the realm of a mystery, before suddenly exploding into a full-blown conspiracy thriller/psychological horror game. But the one thing that remains consistent throughout all of these shifts is that the game is funny. Peel back the generic volatility of its surface, and Firewatch remains basically a buddy comedy, and one of the most consistently funny examples of that genre, in any medium, from the past decade.

My playthrough of Firewatch contained more belly laughs than that of any other game I’ve ever played. In fact, it is rare for me to laugh with such abandon, with such unqualified and good-natured mirth, in a work of entertainment of any medium as much as I did during Firewatch. The laughs that I had during Firewatch were not the usual laughs I have watching movies, or television, or theater. They were more like the laughs I share among friends. They were warm and intimate, filled with the feeling of admiring the off-the-cuff cleverness of people you know well and enjoy hanging out with.

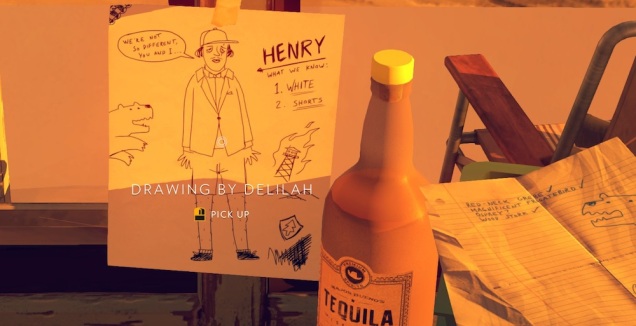

Part of this is the game’s brilliantly minimalist dialogue system. Firewatch takes the Mass Effect approach of “dialogue options give you the gist of what your character will say but don’t spell it out entirely,” and runs with it. Your friend Delilah will call you up on your radio and make some witty comment. You, as Henry, will have a choice of some retort. You sketch out the basics, but what actually comes out of Henry’s mouth is a much more well-written line than you ever could have come up with yourself on the fly. Then, Delialah’s even-more-clever response ups the ante. And so on. The end result feels is a good simulation of idly conversing with a friend (hence, the chummy aspects of the game’s humor), while simultaneously allowing you to play the part of someone quite quick-witted. It is fun talking with Delilah, and it is fun being Henry.

Successes of the dialogue system aside, it is also important to praise the stellar voice acting of Cissy Jones and Rich Sommer, who play Delilah and Henry, respectively. The quality of both of their work, and what it brings to the game as a whole, is hard to overstate. Equal parts charming and vulnerable, witty and prickly, caring and deflecting, Jones’ and Sommer’s performances create real human beings that you would actually want to know, and hang out with. It may be a thankless task, but these two have certainly done more than their part to pull videogame voice acting out of the shadow of its dark ages.

And you know what? I can’t even definitively say that the voice acting in Firewatch is better than that in Oxenfree. Truly, we live in an era that is eager to outrun the sins of the past. I am very happy to be playing games in it.

Gone Home

Developer: The Fullbright Company

Released: 2013

Platforms: Windows, Mac, Linux, PlayStation 4, Xbox One

Since I have been praising the voice work of the games in this sub-list so effusively, I guess I’ll switch things up and acknowledge: I don’t really care for the voice-over in Gone Home.

To be fair, Sarah Grayson does a fine job voicing Sam Greenbriar, and her moments of narration are well-served by Chris Remo’s achingly delicate score. But as affecting as Sam’s story is, I would still venture that it is the weakest of Gone Home‘s stories, judged strictly in terms of its delivery.

Whenever we hear Grayson’s voice on the soundtrack, Gone Home is playing it safe. Diary entries have been a tried-and-true method for delivering game stories at least going back to the original System Shock (Looking Glass Studios, 1994). And plenty of other games in recent years have used the basic format of the radio play bound to a simulated three-dimensional space, including Dear Esther (The Chinese Room, 2012), Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture (The Chinese Room, 2015), and Fragments of Him (Sassybot, 2016).

Gone Home is at its best when it ditches the crutches of diary entries and voice acting. Where Gone Home‘s true strength lies—and where it stands head-and-shoulders over the output of The Chinese Room, which I considered to be overrated—is in its environmental storytelling.

Ah, yes. Environmental storytelling. Wasn’t this supposed to be what games were good at? Wasn’t this supposed to be the defining feature of the medium as a narrative form? This argument has floated around in the academic literature since the publication of Henry Jenkins’ 2005 essay “Game Design as Narrative Architecture,” and in the game design sphere for far longer. But for all of the faith the medium’s designers and players supposedly have in this technique, very few games have been confident enough to ditch puzzles, pixel hunting, mazes, or dialogue trees (the standard fig leaves of adventure games).

Gone Home has that confidence. And its confidence is earned. Once you get beyond the underwhelmingly conservative presentation of Sam’s story, the game’s best character beats all take the form of details sprinkled throughout the mise-en-scène: A concert ticket, discarded in an air vent. A torn-up-letter, mysteriously placed in a hard-to-spot false bottom of a desk drawer. A defaced painting. Lights that burn out, and lights that never turn on. A condom. A child’s height chart.

It is the old cliché of Gothic fiction, where environments become extensions of the personalities of those inhabiting it. Jan and Terry Greenbriar have no dialogue in Gone Home; nor do they have a physical presence. But merely by being in the presence of their home and their belongings, we gain a richer understanding of their hopes, fears, and insecurities than most games ever offer for any characters. Simply poking around in a closet or a dresser can provoke moments of humor, moments of sadness, even moments of dawning terror. These people have led rich, complicated, flawed lives.

I am going to go out on a limb and say that, out of all of my games of the decade, Gone Home feels the most necessary. Not strictly because of its story or its characters, but because of the sheer chutzpah of its delivery. Yes, it is the game that launched a thousand “not a game” tirades. But it did so by having the courage of its convictions, and the audacity to allow environmental storytelling to stand on its own, unaided by arbitrary challenges. Whether its gamble will truly change the course of gaming history remains to be seen. Regardless, though, it remains one of the decade’s most essential experiments.

The Sea Will Claim Everything

Developer: Jonas and Verena Kyratzes

Released: 2012

Platforms: Windows

“The personal is political,” went the feminist rallying cry of the 1970s. It’s easy to lose sight of the fact that the inverse is also true: one’s politics are personal. Not in the sense that they should be kept to one’s self, but rather in the sense that they touch the very core of our personalities. Knowing someone’s politics is a crucial part of knowing them, intimately. Even if you disagree, it’s not really possible to be a close friend or lover to someone unless where you know where they stand on some issues.

I love Jonas and Verena Kyratzes’ adventure game The Sea Will Claim Everything for many reasons. I love the wit and whimsy of Jonas’ writing, its endless walls of flavor text, the fact that each and every mushroom is given a personality. I love the color and character of Verena’s illustrations, her ability to make the whole thing feel like a lived-in storybook. I love Chris Christodoulou’s lush and quietly contemplative score.

But, perhaps above all, I love how much I get a sense of knowing the Kyratzes after playing the game—Jonas, in particular. This includes knowing his politics. I know his feelings on neoliberalism, and what must be done to combat its insidious logic. I know his reactions to post-recession Greek austerity programs. I know his thoughts on the moral imperative of building and maintaining a community. And I know his taste in books: political tomes, yes, but also academic books, science fiction books, fantasy books. Oh, the books. So, so many books, piled up along almost every surface in The Sea Will Claim Everything.

When awkward graduate students get together for parties at each others’ apartment, there will always be a contingent of them perusing the host’s bookshelf. This is how we connect: it is the necessary prerequisite for larger conversations. Conversation flows not about current events or interpersonal relationships, but rather the paperback spines on display. “Oh, you read this? What do you think? Oh, you have a copy of this? It’s quite rare!” For folks of a certain personality, inspecting someone’s bookshelf is a requisite “getting-to-know-you” gesture.

The Sea Will Claim Everything is one of the few games to understand the pleasures of making someone’s acquaintance in this way. We come to know its characters through dialogue, yes. We come to know them through Verena’s illustrations of their abodes, and the objects that populate them. But we also—perhaps most of all—get to know them through their books. So, so many spines to click through, to inspect, to draw conclusions from. I Stepped on the Frankfurt School and It Made a Squishy Sound, by Giganticus Beantrinket. Famous People I Have Licked, by Corben Argyle-Lamb. Das Kapital, by Carl Marx.

It is through these titles that I feel I know the characters in The Sea Will Claim Everything. I know their interests. I know their passions. I know their levels of educational attainment. I know their politics. These are things I have never gotten to know about characters in other games. They are intimate things, essential things.

And, through these characters, I feel like I know Jonas and Verena Kyratzes, as well. Or, at least, I know them as well as anyone whose bookshelf I ever perused.

The Last Guardian

Developer: Team ICO (begun by) / genDESIGN (finished by)

Released: 2016

Platforms: PlayStation 4

One of my favorite things to show students when demonstrating the power of proceduralism is Robin Burkinshaw’s small browser-based Unity experiment Companion (2012). Through a startlingly small set of rather simple behaviors, Burkinshaw is able to instill the sense that a pink cube on a screen is a genuine character, with identifiable traits: naïveté, playfulness, a lack of caution, vulnerability. Spending five minutes presents a quick primer on how rules and coded behaviors open up ways of establishing character that are utterly unique to digital media, far removed from the usual literary methods.

The Last Guardian isn’t quite as easy as Companion to teach. It is about a dozen hours long, and it is exclusively tied to one specific console. But I’ll be damned if it isn’t everything I find fascinating about Companion, massively blown up in scale. Companion was created in 48 hours, for the Ludum Dare game jam. The Last Guardian had a famously protracted nine-year development cycle. (During this time, its original development team, Sony Computer Entertainment Japan Studio’s subsidiary Team ICO, disbanded, meaning that the game had to be finished by lead developer Fumito Ueda’s new studio, genDESIGN.) And so The Last Guardian doesn’t just illustrate how to create a character through AI routines. It illustrates how to effectively use that character over a 12-hour story, one that explodes into big-budget spectacle, and is is frequently emotionally harrowing.

The character in question, Trico, is a gargantuan chimera that seems to be part cat, part dog, and part bird. Trico is a marvel, not only in his visual design, but also because making your constant AI companion be an animal proved to be a masterstroke. Trico doesn’t always do what you want it to do. Sometimes, it ignores directions. Other times, it follows them, but in ways that aren’t particular helpful. These are things that one would swear at a “human” companion character for, that would reveal the profound limitations of videogame AI. But here, they are so deeply embedded into Trico’s overall design that they feel like character traits, rather than programming limitations. Trico’s character animations and noises (that sound design!) together suggest a nonhuman intelligence, not always on your wavelength, but with definite personality. Sometimes, Trico gets confused by commands; other times, it seems to willfully ignore them, displaying cat-like indifference. But even in my moments of deepest frustration, my reaction was always, “oh, Trico’s not getting it,” and never, “oh, this is some very poorly-coded pathfinding.” That, right there, is the power of great design: when an overwhelming sense of an animal’s personality can emerge from AI, animations, sound design, and a player’s willful imagination, rather than conventional writing.

Given The Last Guardian‘s troubled development (along with Walden, it is one of two “Games of the Decade” on this list to be in development for pretty much the entire decade), I was deeply afraid that the product we finally got, if we got anything, might be obviously broken or incomplete. Thankfully, it isn’t—which is not to say it is perfect. It isn’t. Its most egregious woes stem from how poorly Team ICO’s approach to the control and animation of the player-character has aged. Now that the Assassin’s Creed franchise, the Uncharted franchise, and smaller-scale efforts such as INSIDE (Playdead, 2016) and Little Nightmares (Tarsier Studios, 2017) have all pushed the envelope on binding fluid character animations together with tight controls, the whole “well, finicky controls are just the price you pay for gorgeous animations in a cinematic platformer” excuse holds less water. The Last Guardian‘s controls are egregiously bad, and the occasional twitchiness of its player-character animation distracts from its other production values.

But, as I stated upfront, this isn’t a list of games that are perfect. It’s a list of games that deserve to be wholeheartedly recommended. And if the creation of Trico doesn’t merit a recommendation, I’m not sure what does.

Honorable Mentions

Well, I already mentioned them above, so I suppose I’ll give them a proper place here:

Formulaic or no, the first season of Telltale’s The Walking Dead is a genuinely great game. The fact that I now prefer other adventure games over it should not dissuade anyone from playing it.

Heavy Rain, on the other hand, is not a genuinely great game. Its writing is hackneyed, full of cheats, plot holes, and the occasional bizarre misuse of English. Its score is well-implemented, but also has themes that are outright stolen from Michael Nyman’s score for Gattaca. (Seriously: listen to this and this back to back. I’m genuinely surprised there wasn’t a lawsuit, given the kerfuffle over Harry Gregson-William’s poaching of Georgy Sviridov for Metal Gear Solid‘s theme.) But although these clear issues have worn down my propensity to recommend it over the years, it still remains one of the decade’s more noteworthy big-budget experiments.

Between the release of The Walking Dead and the release of Oxenfree, I’d wager that Life Is Strange (DONTNOD Entertainment, 2015) briefly held the crown as the most stunning story-driven adventure game around. It is a game that has justly been given a lot of love. It has also been subject to a fair amount of criticism of how it handles queer relationships, as well as trigger-heavy content such as date rape and suicide. For my own part, I am thrilled that we can be having these conversations: seeing the medium stumble as it tackles some of these issues seriously for the first time is far preferable to having it never tackle them at all. But after strenuously qualifying my praise for Persona 4, I was wary about including another game in the main list with missteps in queer representation. And so it ended up down here, instead.