It has become a set of dual clichés: in videogames, you either save the princess, or you save the world. Those are the only sets of storytelling stakes offered. The only things that can imbue our actions with importance is to tie our success or failure to the fate of humankind, or the fate of a particular monarchic lineage.

Which is, frankly, alarmingly dumb. By way of contrast, here are some of the resolutions of the great works of cinema: A boy loses respect for his father after the father resorts to thievery. A group of reporters trying to decipher a newspaper tycoon’s last words ponder whether it’s truly possible to know and understand another person. A man and his dying wife are struck by the kindness of their widowed daughter-in-law. The fate of the world does not hang in the balance in any of these scenarios. The stakes in play are emotional, familial, and cultural.

So, whenever a game comes along that gives you a different motivation for caring about its central conflict, that is something to be savored and celebrated. The games listed here all roundly reject tired “save the princess/save the world” narrative stakes. Instead, they offer up goals, character motivations, and resoultions that are more personal, more intimate, or more philosophical. There is, if it can be said, much more at stake in these games than the fate of the world.

Gravitation

Developer: Jason Rohrer

Released: 2008

Platforms: Windows, Mac [broken on newer Macs], Linux, Nintendo DS

As I noted in my introduction to this list, Jason Rohrer released Passage on November 1, 2007, hot on the tails of Portal, an integral part of that crucial year in which the conversation around videogames began to shift. He has had a busy decade since. He has released a game a year, which has including some ambitious experiments in multiplayer game design, such as Between (2008), Sleep Is Death (2010), and The Castle Doctrine (2014). Outside of his commerically-released output, he made Chain World (2011) and A Game for Someone (2013), two bold experiments in philosophical game art. In 2016, he became the first videogame developer to get a solo museum exhibition, when The Game Worlds of Jason Rohrer opened at Wellesley College’s Davis Museum.

I haven’t been able to keep up with all of Rohrer’s output over the past decade, so I cannot speak authoritatively about the “best” Rohrer game. Luckily, though, this list isn’t about “best” games, but instead about those I’m the most happy to recommend. And I am quite happy to recommend Gravitation as a representative example of Rohrer’s output.

Gravitation is a simple parable, executed with serene precision in its game mechanics. (The game is an excellent example of what Ian Bogost terms the proceduralist style of minimalist game design, laser-focused on a particular mechanical metaphor.) It is about work-life balance and masculine identity—specifically, the masculine identity of being simultaneously an artist and a provider for one’s family, split between the siren call of manic fits of inspiration and the everyday responsibilities and joys of being a good father. Over the course of eight minutes, it accomplishes something that a thousand stories about negligent parenting have failed at: it genuinely presents work as rewarding, models the psychological pull it has over us, and tempts us to upset the balance between personal ambition and parental responsibility. It is a lean, elegant example of how game mechanics can use psychological rewards to impart messages.

It should be said that Gravitation is not Rohrer’s most ambitious or theoretically interesting game. As a single-player game, is lacks the rich experimentation of Between or The Castle Doctrine. The upside, though, is that your experience of it is not tethered to what other players are up to online. I suppose I am being conservative, but that left it easier to recommend, for me.

Papers, Please

Developer: 3909

Released: 2013

Platforms: Windows, Mac, Linux, iOS, PlayStation Vita

At least as far back as when Sherry Turkle first noted the political assumptions embedded in citizen’s reactions to SimCity tax rates, people have recognized that games can enact messages through their systems. These days, this phenomenon is usually referred to under the heading of “procedural rhetoric,” in the wake of Ian Bogost’s writing. The idea, though, is older than that, snaking through the writings of Turkle, Chris Crawford, Noah Wardrip-Fruin, and Michael Mateas.

There is a danger, when talking about messages that are communicated through systems, mechanics, and procedures, to assume that players’ reception of these messages must be a cold and logical one. Nothing could be further from the truth. Games use emotions just as much as any medium when imparting messages. In fact, they have access to a slightly expanded suite of them: Fear, but also frustration. Relief, but also pride. Anger, but also guilt.

Lucas Pope’s Papers, Please understands this well. There is nothing particularly daring about the political message of Papers, Please. Stated in a few words, it boils down to “living under and within a totalitarian bureaucracy is hellish, and every day brings with it new moral compromises.” But although each of us might read that statement and nod in agreement with it, Papers, Please goes out of its way to make us feel it. Following in the footsteps of Cart Life (Richard Hofmeier, 2011)—a game that Papers, Please edged off this list, given that it is both more easily obtainable and less bug-ridden—Papers, Please is a game about one’s livelihood. It is a game about making enough money each day to keep a roof over the head of one’s family, to keep them fed, warm, and healthy. In Papers, Please, the immediate penalties of failure might be witnessing a family member die because you didn’t have enough money to buy medicine for them. The long-term consequences, though, might be a slow-acting moral rot that sees you accepting bribes or enforcing unjust orders to prevent this from happening again.

Papers, Please likely isn’t a game that will change anyone’s mind about anything. (Who doesn’t already think that totalitarian dystopias are bad?) But it stands as a major step forward in leveraging our emotional reactions to systems as rhetorical devices. With luck, we will see more games in the coming decade building upon its lessons.

To the Moon

Developer: Freebird Games

Released: 2011

Platforms: Windows, Mac, Linux, iOS, Android

To the Moon begins, right out of the gate, with the following premise: What if the memory-altering technology from Philip K. Dick’s “We Can Remember It for You Wholesale” (and, subsequently, Paul Verhoeven’s Total Recall) didn’t lead to people too busy to go on vacations implanting memories of going to Mars? What if it was reserved for use as part of hospice care, erasing the regrets of people on their deathbeds, allowing them to pass on in peace, imagining they had lived a life they actually hadn’t?

It speaks to To the Moon‘s self-assuredness that this premise is delivered in an almost tossed-off manner, with few people really commenting on it or explaining it in depth. To the Moon is refreshingly free of the tendency toward over-exposition that often mars works of meticulous world-building. Instead, Kan Gao, the game’s creator, is mainly interested in this world insofar as it provides him the means to weave the story he wants to weave. And he has chosen to weave an achingly sentimental love story between a man and the non-neurotypical love of his life. There are twists. There are turns. There are tears. Oh, my, how there are tears. They proceed from the incidents in the game’s plot, their inevitable release further lubricated by Gao’s self-composed, achingly melancholy score. Never has MIDI piano plinking moved me so much. It recalls Uematsu Nobuo’s 16-bit era work and, to my ear, surpasses it. (I am, admittedly, a sucker for musical schmaltz.)

Like all of the games on this list, To the Moon is not perfect. It occasionally throws an unsatisfying puzzle at the player, as if trying to head off the dreaded “barely interactive” epitaph, when actually it would be better off being what it actually is, without shame. (For the record, it is a linear visual novel, bereft of player choice, illustrated with gorgeous pixel art. I pass no judgement on this form. It is precisely what it needs to be—at least, it would be, sans the puzzles.) It also makes a somewhat concerning attempt to turn autism spectrum disorder into the tuberculosis of the 21st century: a romantic ailment, signaling the affected woman’s innocence and purity, a handy signpost that they are “too good for this world.”

But, though not flawless, To the Moon gets a lot of mileage out of the rich possibilities of its universe. After spending much of its running time diving deeply into the affecting life story of a dying man, the game adjust its scope at its conclusion, pointing itself towards the ethical concerns of the fictional technology that provides it with its frame. Rather than saving the world, or even saving a single character’s life, To the Moon is about what to do with the memory of a man who has, at most, days to live. Should one give him the good death he seeks, even if that means erasing a life that is, on the whole, well-lived? What becomes of love in a future where our neural pathways can be effortlessly re-written? The fact that To the Moon wrings such genuine emotion from such fantastical premises is to its everlasting credit. There aren’t nearly enough great science fiction love stories out there. The fact that one of them ended up being a videogame feels like a major win for the medium.

The Talos Principle

Developer: Croteam

Released: 2014

Platforms: Windows, Mac, Linux, PlayStation 4, Android

I don’t remember any exact moment when I put together exactly who or what I was playing as in The Talos Principle, and what exactly the history was of the world I was inhabiting. But I do know one thing: it didn’t come in the form of an eleventh-hour twist. For that, I am eternally grateful. Rare is the game that respects player’s intelligence enough to present a thoughtful, philosophical science-fiction premise without stuffing all of the good stuff into the last few moments, as if worried that players will get bored if they are actually asked to ponder the meaning of their actions as they perform them.

When I actually did piece everything together, at my own desired pace, I arrived at the unexpected feeling that this game about re-directing beams of light cast me as probably one of the most important and interesting fictional characters in the history of the medium. Once I realized the significance of it all, what it would actually mean if I were to succeed or to fail, which voices to listen to and why, I was overcome with an almost overwhelming mixture of melancholy and hope. (I should say that your mileage may vary here. I often have unusually emotional reactions to science-fiction yarns that others might find coldly intellectual, as evinced by the vast swarm of feelings Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris can invoke in me.)

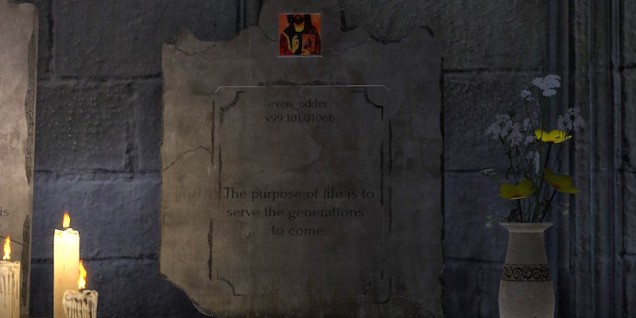

Something bleak has stained the future of humankind in The Talos Principle. But we have also achieved something we can be proud of. Something that required the concentrated efforts of both scientists and humanists. Something that people gave every moment of their lives to. Something that ended up imperfect: unfinished and, by all available evidence, a bit rotten. (Actually, make that bitrotten.) But something vital. A legacy.

It feels strange dancing around the details of The Talos Principle. Putting “spoiler” tags all over the place would do it an injustice, precisely because it is not in its nature to traffic in the twist, the reveal, the mindfuck. It is simply that I do not want to deny anyone the dawning realization of this game’s surprisingly deep core. Puzzle games don’t really need to give motivations for players beyond “hey, figure this thing out.” The fact that one of them would choose to adopt philosophical stakes of this magnitude, filled out via such a well-written and richly characterized science fiction tale, utterly floored me.

(My, I am putting a lot of first-person puzzle games on this list: Portal, The Witness, and now this. I suppose I’ll just attribute it to the zeitgeist of this decade.)

That Dragon, Cancer

Developer: Numinous Games

Released: 2016

Platforms: Windows, Mac, Linux, iOS, OUYA

It might seem as if I am filling up this sub-list with too many games about being a parent. Gravitation. Papers, Please. And now That Dragon, Cancer, Ryan and Amy Green’s autobiographical game about witnessing their five-year-old child die of cancer.

I won’t spend much time here, though, talking about what That Dragon, Cancer has to say about parenting—parenting under the most terrible and heartbreaking circumstances imaginable. I am more interested in That Dragon, Cancer as a game about faith, chronicling how one couple’s mourning opened up a rift in their conceptions of god, as theodicy transformed from a philosophical thought experiment to a gut-wrenching everyday trial dominating their lives.

Production on That Dragon, Cancer began while the Green’s son Joel was still alive. Although the greens collaborated together on the game’s production, with Ryan serving as a designer and Amy as a writer, they had different perspectives on what the game actually would be. Given their son’s prognosis, Ryan conceived the project as a chronicle of love and mourning. Amy’s intentions, though, were different. Although both the Greens are Christians, Amy’s particular approach to faith left her more open to the idea of miracles. She believed that Joel would pull through, and that the game would ultimately stand as a testament to the power of prayer.

Joel Green did not pull through. He died during the production of That Dragon, Cancer.

If one were being heartless, one could say that this means that Ryan’s conception of the game “won” over Amy’s. The end result, though, is much more complicated. That Dragon, Cancer is about the fate of Joel, but it is about so much more than the loss of one life. It is also a chronicle of an intractable struggle between two incompatible conceptions of God—one that, for a time, turned two spouses into villains in each other’s stories, just at the moment they needed each other the most.

It is fairly clear that, if Amy Green had received the miracle she had expected, Ryan Green would have not been portrayed particularly well. Plagued with doubt—if not about God’s existence, than at least about His intervention in human affairs—Ryan could, in a more straightforward religious parable, be cast as he of little faith, the stumbling block to Amy’s devotion.

Since the miracle never arrives, however, Amy’s behavior becomes, in hindsight, almost monstrous. Ryan has doubts about God’s willingness to step into cosmically insignificant human affairs. These doubts are understandable. Ryan rejects the guilt-inducing link between Joel’s recovery and their standing in the eyes of God. If Joel dies, he doesn’t think that it will have been because they didn’t pray hard enough. This seems emotionally healthy. Ryan is doing what he can to emotionally prepare for the reality that his son will likely die. Amy seems bent on destroying this emotional preparedness.

In writing and voice acting their own respective positions during this trial, the Greens exposed to the world an enormous rift in their thinking, one as emotionally raw as anything I can imagine. Amy Green, in the end, was proved wrong in her optimism, but she still had the courage to accurately report on her beliefs. That Dragon, Cancer ends with the Greens emotionally reconciling, despite knowing full well that their conceptions of the universe are still incompatible, and that they are both still screaming out into the void of the ineffable. Because of what these two people went through, That Dragon, Cancer cannot be called an optimistic game. But it is, in the end, an extraordinarily humane one.

Honorable Mentions

I mentioned that it was just edged out of the list proper above, so to make it official: Cart Life (Richard Hofmeier, 2011) is near-essential playing for the decade, held back only by bugs and becoming harder to find after it went free and open source.

A mere four years since its release, Papers, Please has already proven to be an influential game, with some games pushing beyond its rather simple “authoritarianism is awful to live under” political message. Orwell (Osmotic Studios, 2016), for instance, puts a contemporary, post-Eric Snowden spin on the theme of moral culpability, delving into the push-and-pull between temporary security and essential liberty. This debate, of course, lends itself to ham-handed missives, so it’s not particularly surprising that Orwell (2016) is clunky at times. Some of its design decisions, though—for instance, the ability to successfully thwart a bombing early in the game if you are quick-witted enough—are quite brilliant, and make the whole experience morally richer than it could have been. Although it’s not rhetorically robust enough to change anyone’s mind on things like the PRISM program, it is worth a hat-tip.