Ian here—

The following is the assignment description for a three-page comparative gameplay experience reflection that I assigned students at about the halfway point of my course “Comparative Media Poetics: Cinema and Videogames.” The theme of this particular week was “Emotion and Identification,” with an emphasis on the differences in both of these things across cinema and games. Students read a selection from Carol Clover’s Men, Women, and Chain Saws on horror and cross-gender identification, portions of Noël Carroll’s The Philosophy of Horror where he expresses skepticism toward the term “identification” and plots out his own theory of our emotional reactions to film based in then-recent analytical philosophy, and a chapter from Grant Tavinor’s The Art of Videogames in which he adapts this same analytical tradition of theorizing about art and the emotions to videogames.

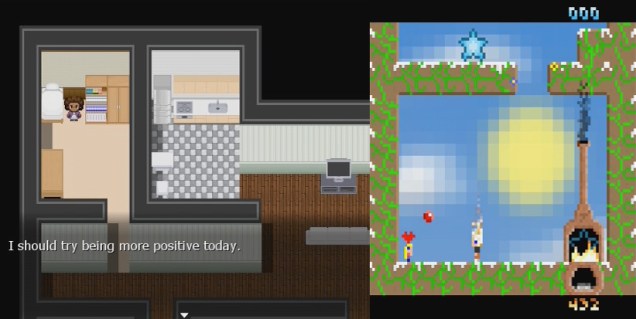

I also assigned students to read Vivian Sobchack’s essay “Breadcrumbs in the Forest: Three Meditations on Being Lost in Space,” because for this assignment I wanted students to focus on a very specific feeling, and how it is translated across different media: the feeling of being lost. Cinema can present us with stories in which we identify with characters that are lost. But videogames can actually make us lost, and cause us to adopt all of the usual behaviors one turns to when lost. I wanted students to plumb this difference in their gameplay experience reflection.

The two case studies I settled on here were Gus Van Sant’s film Gerry (2002) and The Path (2009), a game by Auriea Harvey and Michaël Samyn, who together make up the Belgian art group/game studio Tale of Tales. I later resurrected this specific comparison in my SAIC first-year seminar course “The Moving and Interactive Image,” where I adapted the assignment description that follows into a lesson plan, using the following questions to animate in-class discussion, rather than form the basis for a paper.