(I’m officially retiring my usual “Ian here” greeting, as, in the absence of student posts, there will be no one but me posting on this blog for the foreseeable future.)

Early in his book Pilgrim in the Microworld, a phenomenological account of videogame expertise that stands as landmark work of first-person game criticism, David Sudnow attempts to describe, to a presumably completely ignorant reader, the experience of playing Breakout (Atari, 1972). “There’s that world space over there, this one over here,” he writes, “and we traverse the wired gap with motions that make us nonetheless feel in a balanced extending touch with things.”[i]

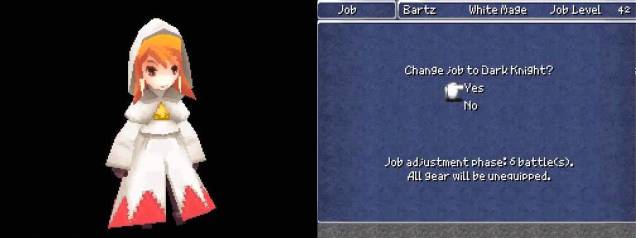

Today, the term “wired gap” is archaic—we sit comfortably in the age of wireless game controllers. But the general logic of this gap, and how it is traversed, nonetheless persists. On the one side, we have the electronic world represented on the screen. On the other side, we have ourselves, cordoned off from the world of the game by virtue of being flesh-and-blood. If we act upon that other world from our side of the screen, it must be by virtue of some sort of electronic input device: keyboard and mouse, DualShock 4, Wii Remote, Jungle Beat bongo drum, what have you. Wired or not, the relationship we have with that world on the other side of the screen is necessarily mediated by technology: sever that particular link, and our involvement with it ceases.

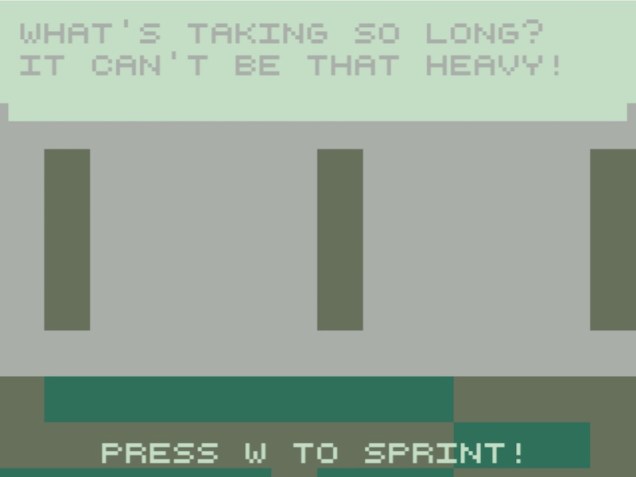

Not all games follow this logic, however. In this post, I’ll be looking at three games, all of which came out around 2012–2014, that ask you to do more, as a player, than simply manipulate an electronic interface. These games have a different sort of contract with their player. They ask you agree to more wide-ranging sets of behaviors over on your side of the screen, which, by their very nature, cannot be regulated in strict procedural terms. These are games that re-map the points of contact between our fleshy, spacious realm and the realm of bits and pixels.