In general, Alfred Hitchcock’s treatment of women in his films is a subject of considerable analysis and debate. On one hand, some critics argue that Hitchcock’s portrayals of women can be seen as problematic due to the recurring themes of obsession, manipulation, and violence against female characters in many of his films. These portrayals often fit within the framework of the “Hitchcock Blonde” archetype, characterized by icy beauty, vulnerability, and often serving as objects of desire or victims of male aggression.

However, others argue that Hitchcock’s treatment of women is more complex and nuanced. While his female characters may sometimes fall victim to violence or manipulation, they are also often depicted as resourceful, intelligent, and capable of agency. Many of his films feature strong female protagonists who actively engage in the plot and challenge traditional gender roles. Additionally, Hitchcock’s films often explore themes related to gender, power dynamics, and the complexities of human relationships. His portrayal of women can be seen as a reflection of these broader themes rather than a straightforward endorsement of sexist attitudes.

While watching Rear Window, I found the gender dynamics particularly intriguing, especially concerning the roles each character assumed in the unfolding investigation. As the narrative progressed, a notable shift emerged in the portrayal of women and their involvement in the investigative process. Initially, Lisa was depicted solely as Jeffries’ youthful, fashionable girlfriend. Similarly, Stella was confined to the role of a nurse, “Ms. Torso” served as little more than eye candy, and Mrs. Thorwald appeared as a stereotypical nagging wife.

During the film’s early stages and well into the investigation, these women predominantly functioned as objects of desire and victims of male dominance (with Stella being a possible exception, albeit still constrained within a nurturing, feminine role). However, as the plot advanced, a transformation unfolded, granting these characters opportunities to showcase resourcefulness, courage, and intelligence. This evolution is what captivated me the most and what I intend to explore further in the rest of this blog post.

For starters, Lisa is often seen as the epitome of the Hitchcock Blonde archetype I previously mentioned—beautiful, elegant, and sophisticated. Initially, she appears to be the quintessential socialite, concerned primarily with fashion and parties. However, as the film progresses, Lisa’s character evolves. She demonstrates intelligence, courage, and a willingness to challenge societal expectations. Her determination to prove herself to Jeffries by participating in his investigation of Thorwald is seen as a departure from traditional gender roles. Despite initial skepticism from Jeffries and others, Lisa’s determination and resourcefulness ultimately prove invaluable to the investigation.

Her willingness to challenge traditional gender roles by involving herself in the dangerous pursuit of truth signifies a shift within her, and allows her to become more aligned with Jeffries (who, as a photographer, regularly pursues the truth in dangerous situations). Ultimately, we see this shift represented in the final moments of the film that depict Lisa, now wearing jeans and reading Beyond the High Himalayas by William O. Douglas, as she lounges in Jeffries apartment. The more casual nature of their duo in this scene suggests that the character arc Lisa had through the movie was significant in moving her and Jeffries relationship to the next level.

In addition to this, Stella serves as Jeffries’s pragmatic and down-to-earth confidante. As his nurse, she provides valuable insight and commentary on the events unfolding outside Jeffries’s window. Stella is portrayed as wise and observant, offering a contrast to the more glamorous Lisa. Her role highlights the importance of female intuition and practicality in navigating the complexities of life.

Stella possesses keen observational skills and an interest in the gorey details that rival even those of Jeffries himself. Her pragmatic insights and practical advice contribute to Jeffries’ understanding of the events unfolding outside his window. As a character, Stella serves to reinforce the idea that effective investigation often requires a combination of intuition and practicality, qualities traditionally associated with femininity. While, ultimately, Stella’s role in the investigation is not as in depth as Lisa’s, her contributions are incredibly helpful to the team as they attempt to piece everything together. Also, like Lisa, the investigation changes Stella as a person, evolving her character from “the nurse” to a key investigator.

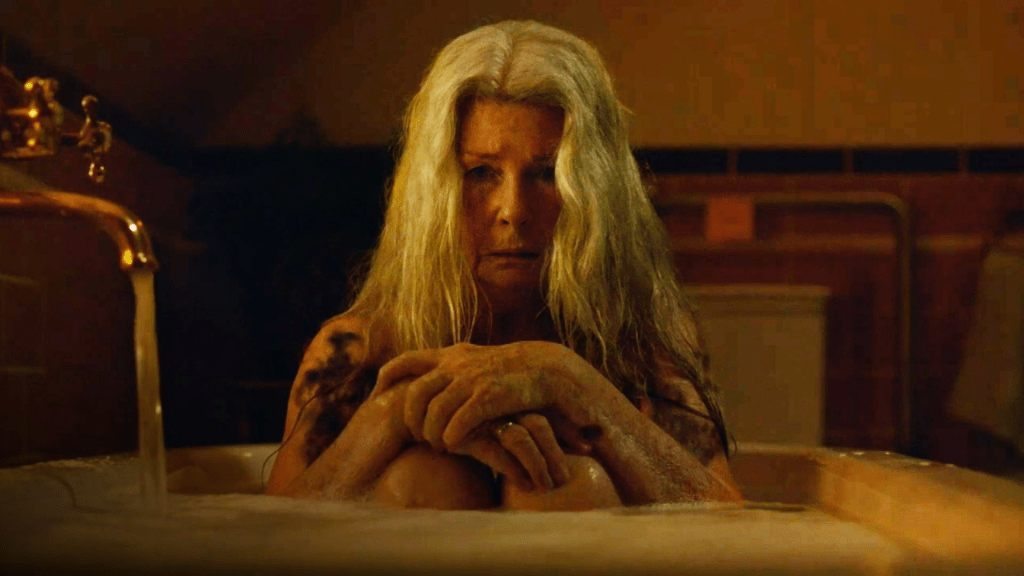

Lastly, Mrs. Thorwald is a key figure in the film, despite her limited screen time. Her absence from the apartment and Jeffries’s suspicions about her well-being drive much of the suspense. Mrs. Thorwald’s character is largely defined by her relationship with her husband, Lars Thorwald, and her mysterious disappearance is what fuels Jeffries’s investigation. As the victim, Mrs. Thorwald is one of the only main women in the film to not go through a significant transformation, instead relegated only to an object of mens aggression.

Some interpretations suggest that Mrs. Thorwald’s plight serves as a commentary on the vulnerability of women within the confines of domestic life, with her mysterious disappearance, as well as the glimpses of other women observed through Jeffries’s window, offer a lens through which to explore the themes of vulnerability and victimization. Throughout the film, Jeffries observes various women in the apartments across from his own, each offering glimpses into their lives and relationships, indicating unequal power dynamics between them. Despite being physically confined to his apartment, Jeffries exercises a form of voyeuristic control over the women he watches, a dynamic that raises questions about agency, consent, and the ethics of surveillance.

Overall, though, I believe women are portrayed in a very positive light in this film. I believe it to be intentionally subversive to have these women begin the film in very limited roles, as objects of men’s desire and/or aggression, but then through the course of the film and the investigation to break those gender roles, to be transformed by the experience. – Sallie

(Image credit: exceeding09 at

(Image credit: exceeding09 at