I will shock no one by saying that videogames, like architecture, sculpture, or gardening, have the potential to be a richly spatial art form. It has been twenty years now since Janet Murray, after playing DOOM (id Software, 1993), reported that “the fluid navigation through the enormous three-dimensional spaces was rapturous in itself.”[i] It has been nearly as long since Espen Aarseth characterized games as being, above all else, “essentially concerned with spatial representation and negotiation.”[ii]

And so, while my last three categories (“pacing,” “characters,” “stakes”) have been elements of storytelling common to any form of narrative, I wanted to call this category something other than simply “setting.” Videogames don’t have “settings” in the same way that literary works do. They offer up spaces, places, worlds: opportunities for virtual exploration that exceed the possibilities of non-interactive media in their richness.

And so the games on this list don’t just just represent my favorite “settings.” They offer up some of my favorite places to visit, to spend time in, to explore, to discover.

One last thing before we start: I was personally surprised by how few games with fully-rendered 3D graphics showed up on this list. I find few things as pleasurable as the simple act of navigating a virtual 3D space, and yet here, in my category devoted to places, that preference is thoroughly subverted. I would like to think that that speaks to the high quality of these games: high enough to burst through my usual prejudices.

Undertale

Developer: Toby Fox

Released: 2015

Platforms: Windows, Mac, Linux, PlayStation 4, PlayStation Vita

Toby Fox’s Undertale is a game that could have gone many places on this list. I could have placed it under my “characters” category. (Certainly, the game’s enduring popularity as an inspiration for fan art has demonstrated that its characters worm their way into player’s hearts.) I could have placed it under my “stakes” category. (Although it flirts with “save-the-world”-isms, its ultimate construction is more intricate, and allows for a startling depth of moral culpability.) I could have placed it under my “ambition” category. (It boldly re-writes the rules of RPG combat and conversation, turning every battle into the chance to make a new friend. It’s almost a rift on Edge Magazine’s much-parodied lament, back in 1993, that DOOM would be so much more captivating “if you could talk to these creatures.”)

In then end, though, I chose to place this game—which, I hope I have made clear, is one of the most essential of the past decade—here, in my “sense of place” category. Because the sense of inhabiting a place is precisely what ties together all of the other fantastic attributes of this game.

Undertale is a game in which not killing any enemies is not just one option offered (many games offer that option, which has a particularly rich history within the stealth and RPG genres), but a philosophical choice that definitively alters the social world around you. You can be as diplomatic or as violent as you want in Undertale, and the towns you stroll through become friendly or desolate, accordingly. Some people who play Undertale will discover a charming milieu of lovable (if also lonely and emotionally frail) monsters, gradually shifting their generations-old prejudices about humankind. Others will find the equivalents of deserted Wild West towns, occupants quivering and hiding from your black-clad gunslinger. It’s a game with characters so well written that you may never meet them at all, as your reputation will precede you, and their behavior will adjust to avoid you at all cost. It’s a game where you can enjoy the warmth of a tavern full of friends, or march through towns left abandoned by your genocidal tendencies.

It’s also a game that is difficult to write about in 2017. Even though it was released only two years ago (and only about a month ago on consoles), it already feels as if we have reached a saturation point of how much gushing about it the internet can possibly hold. If you’re looking for a rich critical assessment of the game’s successes, one of my personal favorites is Nathan Grayson’s, here. For my part, I will do what I’m here to do: recommend it.

Night in the Woods

Developer: Infinite Fall

Released: 2017

Platforms: Windows, Mac, Linux, PlayStation 4

Above, I noted that Undertale could have very easily been slotted under several of the categories I have broken this list into. Night in the Woods does not have that luxury. Night in the Woods sports some significant deficits in the very areas I have been praising other games on this list for.

Its pacing is severely off, with its second act in particular being a lethargic mess. And its characters, though marvelous in some ways, are held back in others. They possess enormous depth, with unique hopes and fears anchored in very different (and often generationally divergent) life experiences. But whenever they crack a joke, they all speak in the same voice. This conformity of quippy humor spreads a layer of monotony over their otherwise remarkable diversity.

I mentioned these flaws when I wrote about Night in the Woods earlier this year. But, if you read that piece, you also know that Night in the Woods, like everything else on this list, is worth experiencing—even loving—in spite of its flaws.

Despite being inhabited entirely by anthropomorphic animals, Night in the Woods‘ Possum Springs is not, by and large, a fantastical place. It is a familiar one. Possum Springs is an achingly present-tense model of post-recession small town America, accurate in its portrayal of shifting employment and homeownership patterns, substance abuse, and rural depopulation. Yes, as you bounce about in the game’s lazily-paced platforming, discovering hidden nooks and crannies, you will get a sense of the game’s magical realist and weird fiction elements. But despite these colorful fringes, the community of Possum Springs feels distinctly mundane and lived-in. Storefronts are worn down in ways that reflect real-world economic trends. Neighbors teem with life, politics, stories.

I have written before on the function of the horizon in 3D games, the way in which, as literal fact and psychological technique, it entices us to continue exploring, to push ever forward into mystery. Night in the Woods is a game uncommonly unconcerned with horizons. It is a game about putting the breaks on expanding one’s experiences, and returning to the comfort of home (however changed) to re-calibrate. Possum Springs is not some sort of exciting bridge the future: it is small and isolated, curtailed by fences and city limits. Our character, Mae, doesn’t even climb the water tower that catches her eye in the screenshot above. This is an unusual move—typically, if games spend a moment calling our attention to a landmark in the distance, it is because we are eventually going to go there. But Night in the Woods isn’t a typical game. It is not a game about the conquest of new frontiers, the widening of horizons. It is a game about returning home, getting to know it in ways you didn’t when you were a child, coming to appreciate it in all of its hidden complexity. This process can be terrifying (and, indeed, Night in the Woods delves deeply into horror). But it is also part of growing up.

Sunset

Developer: Tale of Tales

Released: 2015

Platforms: Windows, Mac, Linux

Can we just go ahead and agree that this decade I’m marking out, from 2007 until now, was the decade of Tale of Tales?

The Graveyard (2008) was a landmark experiment in art game design, released smack dab in the middle of the October 2007–October 2008 year that I named in my introduction as a major turning point for the medium. It was way ahead of the curve when it came to attracting of stupid “not a game” arguments: in fact, creators Auriea Harvey and Michaël Samyn headed the whole debate off at the pass, adopting the term “notgame” to describe their work. And yet, despite being reviled in certain “true gamer” quarters, it proved to be a vital inspiration for the pacing of Naughty Dog’s big-budget Uncharted 2: Among Thieves (2011).

And Tale of Tales just kept experimenting, relentlessly. The Path (2009) is a rumination on gendered violence in fairy tales, wrapped un in a simulation of getting lost that only the medium of the videogame could ever deliver. (I also have a very strong unverified suspicion that it influenced a sequence in Uncharted 3: Drake’s Deception.) Bientôt l’été (2013) is a Marguerite Duras novel in videogame form, facilitating an oh-so-French philosophical lovers’ quarrel between networked players. Luxuria Superbia (2013) is an iPad tube shooter about consensually fondling someone’s ladybits.

All of these previous experiments had been fascinating. All of them also felt just a tad undercooked, for varying reasons. Harvey and Samyn had inspiration on their side, though, so it seemed just a matter of time before they produced an unqualified masterpiece.

Sunset seemed well poised to be that masterpiece. By the time it released in 2015, in a post-Dear Esther, post-Gone Home era, the gaming landscape seemed especially primed for Tale of Tales’ approach. Furthermore, one could hold out hope that Harvey and Samyn would built upon the lessons learned by newcomers in the space they had long pioneered.

I don’t think that Sunset is an unqualified masterpiece. I do have great affection for the game, though. I love its sense of biding time, of disappearing into menial labor as a way of emotionally coping with a politically turbulent time. And I love how committed it is telling a story across two very different scales. Sunset is the story of Anchuria, a fictional South American country facing political upheaval in the 1970s. But it is also very much the story of a single apartment, and the transformations it goes through throughout this upheaval.

This is, strictly speaking, a smart decision. Understanding and respecting one’s constraints is a key component of making great art. Harvey and Samyn were prudent to realize that the budget they were working with was enough to convincingly simulate one apartment, and no more. But beyond simply being smart, it is also immensely rewarding. Over the course of Sunset, a few hundred square feet that you get to know quite intimately become a successful synecdoche for Anchuria as a whole. The freedom cries of rebels and the all-seeing eye of the government echo through this space, manifesting as a misplaced book, a broken statue, or a makeshift shrine.

The story of Sunset‘s release is not a particularly happy one. Leigh Alexander was a consultant on the game. In August 2014, she became public enemy no. 1 for the Gamergate movement. (Well, technically, she was public enemy no. 3, but let us not dwell on that.) As a result, a contingent of “true gamerz” who would have normally been indifferent to Sunset actively rooted for its failure. When the game debuted in May of 2015 to reviews that were more lukewarm than glowing, the internet shuddered with mean-spirited gloating. The game failed to recoup its cost, and, as a direct result, Harvey and Samyn announced that they were abandoning commercial releases in the future. Although the possibility remains for them to continue their work in gallery settings, no new games in the vein of The Graveyard, The Path, or Sunset will be gracing the Steam storefront, accessible to anyone with an internet connection and adventurous tastes. The reactionaries had won. Much like The Beatles’ circumscription within the 1960s, Tale of Tale’s period of artistic relevance began and ended in this 2007–2017 decade.

Putting my “sincere advocate” hat on, I am going to outright say that more people should play Sunset. Also, more people should buy Sunset. (You can get it here, or here, or here.) It is not an unqualified masterpiece. But it is well worth playing, and considerably better than some of the more cautious reviews made it out to be at the time of its release. It is worth playing not only for its gorgeous lighting and eye-popping use of color, for its environmental storytelling, or for its careful simulation of a lived-in place. It is also worth playing just to fight the good fight, to stand on the side of artistic experimentation in the face of agonizingly typical reactionary resistance to “degenerate art.”

Kentucky Route Zero

Developer: Cardboard Computer

Released: 2013– (four of a projected five episodes have been released so far, with the fifth slated for 2018)

Platforms: Windows, Mac, Linux (now); PlayStation 4, Xbox One, Nintendo Switch (upon release of final chapter)

When I play Kentucky Route Zero, I get the distinct sense that it wasn’t made for me.

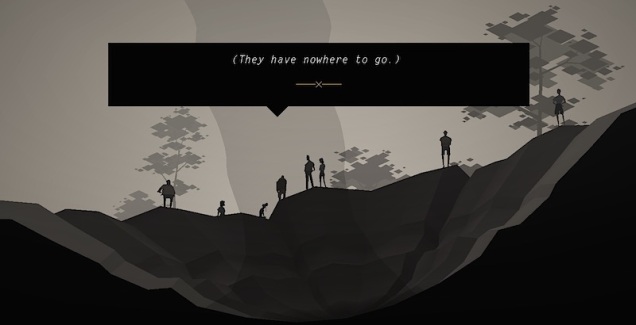

Its art style leverages nostalgia for the PC adventure games and cinematic platformers of the 1990s: something between the blue-gray pixel art of LOOM (Lucasfilm Games, 1990) and the clean vector mountains and caves of Another World (Delphine Software, 1991). Its dialogue and characters, meanwhile, have a distinct literary quality, steeped in a mix of Southern Gothic Americana, absurdism, and magical realism. There is some Flannery O’Connor in there, mixed in with some Beckett, and some Calvino. Sometimes, the allusions are direct; other times there is just a confluence of mood.

So Kentucky Route Zero appears tailor-made for a specific audience: people who spent their youth playing LOOM or Another World, and have a nostalgic yearning for their art styles, but also have an appetite for writing with more literary merit. I do not fit that description. I didn’t play videogames in the 1990s, and my taste in art has always skewed toward the visual and musical over the literary. There is much, I am sure, that goes over my head in Kentucky Route Zero, because I spent my liberal arts college years as a cinema studies major, and not a comp lit major.

So I don’t feel entirely qualified to sing praises for Kentucky Route Zero. At the same time, though, I tried to make it clear in my introduction that this wasn’t going to be a list of my “favorite” games. Instead, it is a list of the games I feel are most deserving of recommendation. And Kentucky Route Zero certainly deserves to be played, far and wide. It especially deserves to be played by people who can better assess its literary merits than I.

What I will say, though, is that Kentucky Route Zero knows how to do setting. It offers up a worn-down, magical realist version of the American South, covered in dust and sweat and electronic mold. Its days are colored with regret—a regret that you can in some cases author, as dialogue choices in this game more often shape a character’s past than their present or future—and sprinkled with allusion. (Again, this is a game that very much should be played by people more well-tuned to literary allusions than I.)

Even though my vocabulary to talk about the game’s successes is limited, there is one thing I can say: the way it upends standard theories about “immersion” is completely astounding. The conventional wisdom is that players will feel like they are more “in” a game world the more you present a virtual view of 3D space, stripped free of text and other UI elements. I have rarely felt more absorbed into the place of a game, though, as when I have been scrutinizing the maps of Kentucky Route Zero. Whether I am dragging my vehicle’s cursor across surface roads, or ringing around the unfathomable subterranean loop of Route Zero, I have rarely felt to enraptured, so absorbed, so included within a game’s space than I have the unpredictable, vignette-filled corners of Kentucky Route Zero. Most games with 100 million dollar budgets struggle to achieve the rich, spatial world-building that this game accomplishes with just a few black-and-white maps, wireframe illustrations, and little text vignettes.

Oh, and although not an official part of the game, the spin-off “interstices chapters” Limits & Demonstrations (2013), The Entertainment (2013), and Here and There Along the Echo (2014) are well worth checking out, as well. Even more than Kentucky Route Zero, they stand as some of the most robust experiments in interactive electronic entertainment in the past decade.

Dark Souls

Developer: From Software

Released: 2011

Platforms: PlayStation 3, Xbox 360, Xbox One (via Xbox 360 backwards compatibility), Windows

In my introductory post, I said that this list was biased towards games that were easy to play. I said that these would be “gateway games”: games that non-gamers might find easy to approach, from both the point of view of skill and the point of view of subject matter.

Dark Souls is very much not one of those games. Dark Souls is not accessible. It is not easy. It is famously tough as nails.

And yet there’s really no way to make a list of the most interesting and enchanting games of the past decade without including Dark Souls. And there is certainly no way of making a sub-list devoted entirely to “sense of place” that doesn’t include Dark Souls.

I played the first third or so of Dark Souls in the company of my friend Daniel Johnson, a genuine expert on the game whose knowledge blends the obsessiveness of a geek with the meticulousness of an academic. Because of his constant guiding hand, I wasn’t able to come to discoveries about this world through From Software’s preferred method of reading elaborate descriptions of inventory items collected from dead foes and allies. I am, then, not the best advocate for From’s unique approach to world-building and lore dissemination.

And, to be perfectly honest, even if my introduction to Dark Souls hadn’t been shaped in this way, I still wouldn’t have been the greatest advocate. I have a less than all-consuming interest in hunting down lore in games, and, on top of that, dark fantasy really isn’t my thing. But I am glad that these elements of obscure storytelling are there, for those who appreciate them.

What I remember from Dark Souls are the twists and turns of its landscapes. The game’s striking sense of verticality. The way its nest of shortcuts and hidden passages contain no geographical cheats, but still feel just as confusing and tangled as an exercise in protein folding. The way in which, despite this confusion, you press on, and eventually get to know these environments—for which there is no in-game map—like the back of your hand. The way in which certain sounds ringing through the air, or sudden changes in lighting, can prompt either a sense of relief (a blacksmith is nearby!) or of dread (I am entering Blightown!).

I wouldn’t blame you if you decided Dark Souls isn’t your thing. My recommendation of it arrives with severe qualifications. It is unforgiving and severe, in both its difficulty and its obfuscated storytelling. But it remains a master class in level design, of creating places that are fascinating, even if all you want to do is survive long enough to get the hell out of them.

Honorable Mentions

Antichamber (Alexander Bruce, 2013) would have without a doubt made the main list if it had retained the sense of absolute, confounding mystery and rich revelation that marks its first few hours. By the time you reach its end, though, it has long since become a game about pixel-perfect dragging and dropping little strings of colored cubes around. I am not sure why Bruce decided to make this shift in the gameplay. Even thought I took the time to map out every last dead-end of its non-Euclidean space, I left feeling that the game would have been stronger if it was half the length, and had remained strictly in the realm of spatio-psychological fuckery.

I hate, hate, hate so many of the actions that Red Dead Redemption (Rockstar Games, 2010) asks you to take as a player. I hate that, by the end of my playthrough, I had killed 693 non-player characters. (That death toll that is probably larger than that of Clint Eastwood’s entire filmography.) I hated that so many of those killings had been done at the bequest of characters I reviled, that Rockstar had gone out of their way to portray as irredeemable monsters, and yet still forced me to cooperate with in order to advance the story. I grew to hate John Marsten’s impotent self-righteous screeds, as he griped about his supposed deep moral misgivings about doing others’ dirty work, only to go out and murder another two-dozen people, in return for only vague promises of future support. But I will say this: Read Dead Redemption had a fantastic landscape. And Marsten’s eventual return to his family farm, with its calming simulation of farming life stained with the looming suspicion that, as in all good Westerns, his violent past was eventually going to catch up with him, was a brilliant interlude. I have a hard time returning to its mountains and deserts, though, without being pained by memories of all the blood spilled there.

[i]. Murray, Janet H. Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace. New York: Free Press, 1997. Pg 62.

[ii]. Espen Aarseth, “Allegories of Space: The Question of Spatiality in Computer Games,” in Cybertext Yearbook 2000, ed. Markku Eskelinen and Raine Koskimaa (Jyväskylä, Finland: University of Jyväskylä Press, 2001), 154.