By Amanda Chacón

My first thought upon opening the first level of Umurangi Generation was: “Oh no.” This was because my eye had immediately gone to the timer at the top left corner of the screen, telling me I had ten minutes to fulfill multiple objectives. Even within quick-paced combat games, I am a slow and careful player, so how would I be able to fulfill these objectives in time? Short answer: there was no way. But it would take me very little time to realize that this was on purpose.

Umurangi Generation is a Māori game developed and released in 2020 by Origame Digital. The game takes place in a cyberpunk Tauranga, New Zealand, after a mysterious cataclysmic event. The protagonist, a nameless Māori photographer, is tasked with taking and delivering photos of a particular area with a digital camera. As mentioned, the protagonist must take pictures of the required objectives within ten minutes. Fulfilling these objectives in time allows the player to move to the next level and introduces the protagonist to a new mechanic related to the camera, from different lenses to new sliders for picture editing. There are also bonus objectives, which can be fulfilled before delivering the photos for additional camera tools. As for the plot—the player is given no context for the world they have been dropped in. The only way to understand what is happening is to explore this world.

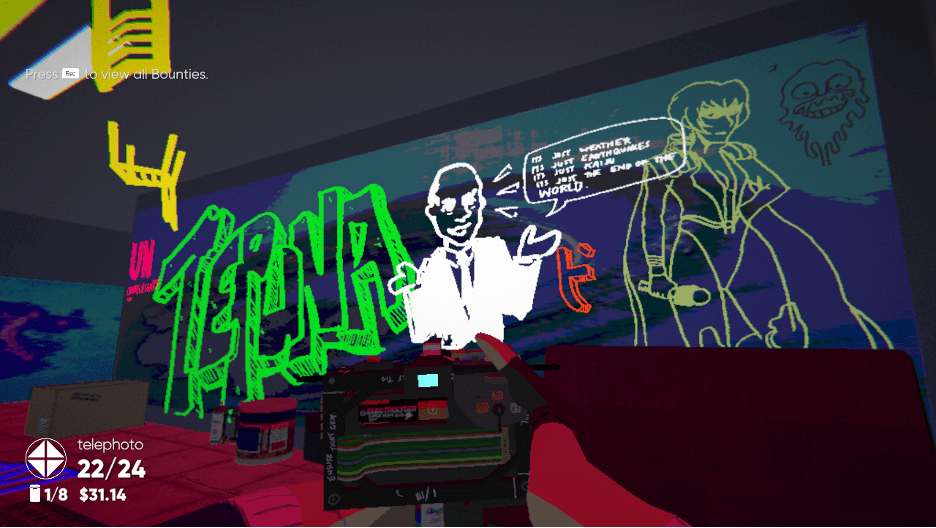

Going back to my experience with the timing mechanic, I had immediately accepted that I would not be able to take all of the necessary pictures in time because I had no idea where the objectives were. I decided to move forward by trying to ignore the timer, instead looking around the setting and searching for “two boomboxes” and a “Union Jack.” While focusing on my surroundings, I began to pick up interesting elements of the landscape. United Nations paraphernalia was everywhere, even in gigantic walls that guarded Tauranga from presumably the ocean beyond. It was through this exploration that I was able to understand the post-apocalyptic nature of the world, and the graffiti everywhere told of a constant feeling of depression and frustration. This environmental storytelling presented, in the terminology of Henry Jenkins, “embedded narratives” suggesting a much larger story beyond the protagonist’s mission to take and deliver pictures. If I had not slowed down to look around, I would not have been able to read the graffiti or question why particular objects were lying around. My experience, as well as those of my classmates, leads me to believe that the impossibility of the time objective is necessary. Once the player accepts that they cannot do everything in time without investigating first, they allow themselves to slow down and take in the embedded narratives.

The apocalyptic environment of Umurangi Generation is emphasized in the fifth available level, named “Contact.” In “Contact” the player is dropped in the middle of a war, taking place in the same area explored in the second level. Even though there is gunfire and dead bodies, the player is given the same timer and set of objectives. Some objectives even match those from the second level to emphasize the destruction the player is witnessing, while others bleakly point to the ongoing tragedy (such as “two body bags”). By looking around, the player is able to make out a gigantic blue jellyfish as the agent of devastation. Bluebottles had been forbidden as a subject of photography at the start of the game—and the player is finally able to understand why. Umurangi Generation is a game that is mechanically based on letting the player interact with their surroundings; it is by moving around and using camera equipment that one is able to take the perfect required picture. Yet, regardless of the ability to fully observe this world, one can’t do anything to stop the active apocalypse. They can’t even help the soldier bleeding out in front of them. “Contact” informs the player that it does not matter if they are equipped with a fancy camera—they are still helpless.

In an interview with The Indie Game Website, main developer Naphtali “Veselekov” Faulkner spoke to this theme of helplessness as inspired by the state of the world in 2020: particularly in the face of the Australian government’s handling of its bush fires and COVID-19 crises. Something that struck me in reading this interview was the idea of normalization. Government attitudes and propaganda take crises and force complacency by adopting the rhetoric of “the new normal.” This message is spray painted all over the game: from the blue bottles (that one is forbidden from acknowledging) to the caricature of a politician saying, “ITS JUST WEATHER/ITS JUST EARTHQUAKES/ITS JUST KAIJU/ITS JUST THE END OF THE WORLD.” As the photographer forced to bear witness to the active ending of the world, the player can only progress if they accept this “new normal” and complete the objectives. The mechanical inability to interact with the plot of Umurangi Generation is thus an intentional critique of neoliberal inertia.

As we discussed in class with Umurangi Generation alongside the other games of the week (Gone Home, Norwood Suite, and Unpacking), limited agency is an important theme in Digital Narratives that enable the player to navigate through a provided space. The ability to move is something the player is allowed to control, so they control what they see. By controlling what one can see, they can control what they understand. This is exemplified by my approach in slowing down and absorbing the embedded narratives in Umurangi Generation. A player can choose to breeze from objective to objective (perhaps after reading or watching a walkthrough) and will likely understand far less about the plot, meaning that they can control how much they can deduce about the story. However, what the player can’t control is the space they inhabit. The world is ending, and the only thing one can do in response is take pictures.