By: Bernadette Broscius

Roberta and Ken Williams (creators of Mystery House)

Individuality/Femininity: Compared to the features and abilities of text-based games like Zork and Adventure there is a distinct difference in Mystery House that goes beyond its visuals. Though it is important to note that this adventure game was one of the first to include computer graphics and expand user interaction in new ways, I find that the origin story of this game to also be a major point of interest. In the 1980’s, married couple Roberta and Ken Williams began working on Mystery House based on Roberta’s inspiration and additionally, her love for mystery games/books. I found it important that this game was inspired by a mystery novel (And Then There Were None), as almost every form of storytelling, even the digital/visual forms can find its roots in written or oral forms of literature. It made me consider the influence that Roberta had not only on the mass video game market, but on women in the later 1980’s. The Nooney reading tells us that “Roberta also knew that games existed on computers prior to playing ADVENT, but she was typically uninterested despite her marginal familiarity with computing…23 ADVENT, however, was something other than the statistical or randomized play scenarios common to mainframe games, and Roberta Williams found herself deeply engaged” (81). With Roberta’s female point of view and understanding that women were hesitant to take part in digital storytelling and gaming, she took these conventional/standard stories that were already popular, and added a twist to it. I think the fact that she recognized the importance of the female market and creating a game that women not only feel comfortable playing, but are interested in was a turning point in the allocation of games such as these. This goes back to my point that the visuals were not the only unique factor about this computer game – the popularity had much to do with “its distribution and its multiplicity, its spread” (Nooney, 78).

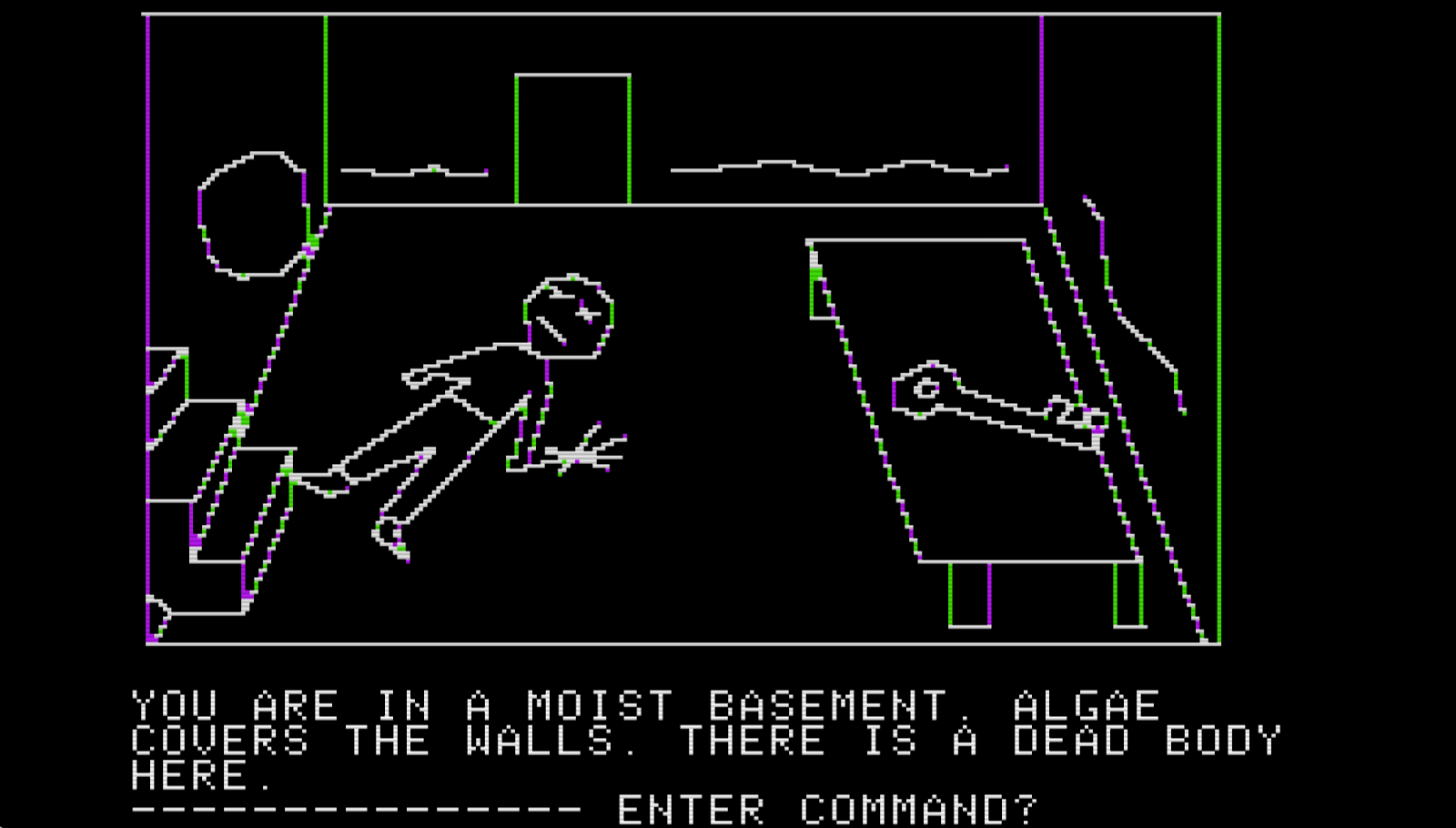

Universal Strengths and Defects: The ability of this game to reach larger audiences due to Roberta and Ken’s teamwork in manufacturing and shipping product, along with the multiple forms of artistic appeal (text, visual, and approachable content) were what made this “novelty.” However, when considering the new and impressive feats that this game introduced, the limitations should also be considered as influences of future works and games. While leading the animation on Mystery House last Wednesday, it was brought up by multiple classmates that the graphics in the game, on occasion, would mislead their game. For example, there is a point in Mystery House where the player encounters a candle. Even so, in my own experience and those of my classmates, we had quite a bit of trouble identifying this object that ultimately becomes necessary for success (the game gets dark and you need a candle). With the limited points that Ken was able to code in each room, the visuals can seem a bit crude or rudimentary. In turn, when a misunderstanding in visuals ensues, the game can be held up for indefinite periods of time, which is profitable for the game, but frustrating for the player. In my case, I ended up having to look up a run-through in order to figure out the specific commands that the text-parser would accept so that I could progress in small ways. Because of my access to technology, I was able to get answers to questions about the mystery that were not initially available at the original release, which positively reinforced my interest in the game. On the other hand, for players that were interminably stuck at a certain point due to the simple text parser and lack of understanding (in terms of the graphics), this might have deterred players from finishing or continuing at all. Even so, at the time, this mystery inspired game drew in a large audience and expanded demographics, despite these shortcomings that I have mentioned, largely due to the rapid progression technology has undergone in the past forty years.

Influence: Another topic worth expanding on that was mentioned in the discussion board, is the influence that this game had on the gaming space today. I found there to be an easy and clear correlation between video games we know now, such as Among Us and Minecraft, as there is a story attached to each of these games that can only be fully understood in addition to the visuals. In newer games, we see that the evolution of graphics has reached new heights and expanded to a point in which the player can see their own character, and see their bodies moving. In class we talked a little bit about how in Mystery House, the navigational experience was limited as you couldn’t physically see your character move, it would just appear in a new room, which made it easy for the player to lose concept of their position. I think that as players began to get used to these simple visuals, it became a next step to introduce the concept of seeing your own character to completely immerse the person behind the screen into the digital world. With this being said, I view Mystery House, with all its originality and its drawbacks, as a great inspiration for new gaming programmers, but also for the player’s interest in digital narratives and machinery. It is also important to consider the female agency included in the storyline of Mystery House (with the killer being a woman named Daisy) that is included because of Roberta’s self-determination and creativity. This game, while it revolutionized computer games in a visual sense, can also be recognized as a reflection of the changes in gender dynamics within the gaming space. Roberta acknowledged that there is space for everyone in the gaming world and was able to do this with such great subtlety that it is only clear when looking at her and Ken’s history.