Ian here—

What follows is my talk from SCMS 2017 in Chicago, IL. It was part of the panel I organized, “Gaming’s Midway Point: Games and Game Culture in Chicago“—and I’d like to thank Julianne Grasso, Daniel Johnson, and Chris Carloy for contributing papers and making that panel the success that it was. You can follow along with my visual presentation here.

This is the website of Collegiate Starleague, a league for competitive, professional-level videogaming, or eSports, on college campuses. Collegiate Starleague holds tournaments for college players of games such as League of Legends (Riot Games, 2009) and Dota 2 (Valve, 2013), two enormously popular games in the Multiplayer Online Battle Arena genre, which has dominated eSports in recent years, as well as the first-person shooters Overwatch (Blizzard, 2016) and Couter-Strike: Global Offensive (Valve, 2012), and the digital collectable card game Hearthstone (Blizzard, 2014).

Most of the teams that belong to Collegiate Starleague are organized as student-run clubs, recognized by their respective schools but operating without official school branding, which is why you get teams with names like the Harvard University Tim’s Foot Stools, the St. Louis College of Pharmacy Cox Inhibitors, and the University of Chicago North Fine Dining.

This is Robert Morris University. It’s seven blocks south and four blocks west of here. It’s a small school, housed in one building, with about 2,700 undergraduates, some of which are spread out among satellite campuses in the Chicago suburbs. RMU is also, thanks to the efforts of its Associate Athletic Director Kurt Melcher, now a historically notable school. RMU, like dozens of other schools throughout the U.S., has an eSports team that competes in Collegiate Starleague-organized tournaments for games such as League of Legends, Dota 2, Counter-Strike: Global Offensive, and Hearthstone. Unlike most of the teams that compete in these tournaments, however, RMU’s team has not been organized by students as a school club. It has, instead, been officially established by Melcher as a University-sponsored varsity sport, with all of the University support that usually comes with that designation. This includes an official practice space, the iBuyPower eSports Arena, put together at a cost of $170,000 as a dedicated lab for student e-athletes, not to be used as a general-purpose computing lab, despite being populated with top-of-the-line PC hardware. It also includes athletic scholarships. In 2014, when RMU first premiered its Universtiy-branded League of Legends team, it made history as the first school in the U.S. to offer athletic scholarships for eSports players.

Melcher reports some small amount of administrative pushback when fully integrating eSports into RMU’s athletic program, especially on fronts such as the cost of the practice facility. But, when I talked to him earlier this month in preparation for this paper, he made it clear that his established position at Robert Morris University helped him successfully re-draw the boundaries of student athletics:

“I think maybe because I came from an athletic background, [the link between eSports and athletics] just sort of made sense, and maybe because I was in traditional athletics as an administrator it made sense. Then, it was just about convincing someone else to see what I saw. I think that was easier just because I had been at Robert Morris for so many years, and they trusted me. … So I had cachet built up, and [they said] ‘Okay, this must be something, because we trust Kurt.”[1]

Describing himself with the improbable designation of a “nerd athlete,” Melcher has been a constant advocate of importing competitive videogames into the college athletics framework, drawing rhetorical parallels between concepts like teamwork across both areas. In his TEDx talk on the possible rise of eSports in college athletics, he had this to say: “I can only tell you this, as over fifteen years as a college coach: The same things it takes to be elite at traditional sports, minus the cardiovascular exertion, are the same things it takes to be elite at eSports. Things like integrity, and character, commitment, technical ability, dedication, your ability to work within a team.”[2]

Now, there are plenty of arguments to be had over whether eSports should be considered sports, and, by all appearances, Melcher is frequently involved in them. Today, though, I want to probe at an issue that doesn’t have to do with the definition of “sport.” Instead, I’d like to look at the intersection of play and labor—at the profit that can be had by leveraging “fun,” and the questions of compensation and exploitation that arise as a result.

Before I get into this area, I want to tip my hand a bit, and acknowledge that any of you looking for a searing exposé on eSports and college athletics will likely be disappointed. I don’t want to create a Maddow-with-Trump’s-tax-returns-style false promise in this area. What I want to offer here is not a puff piece on some charming bit of local flavor, but neither is it a hit piece. It is, instead, a consideration of some complicated issues that arise within the matrix of play and labor, some of which are being battled out just a few blocks away.

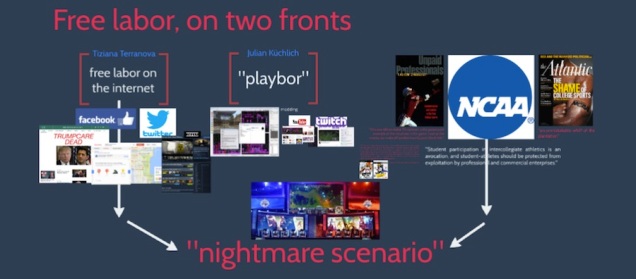

Free labor, on two fronts

Following Tiziana Terranova’s groundbreaking work on the subject all the way back in 2000, scholars of new media industries have tracked the rise of uncompensated labor, freely performed by the internet’s denizens and exploited for profit by its unimaginably wealthy platform owners. The boundaries of what constitutes “uncompensated labor” on the internet are a little fuzzy: One sometimes sees charges of uncompensated labor thrown out against social media companies such as Facebook or Twitter, whose users effectively create the content that other users log in to see—for instance anyone tweeting on the #SCMStudies hashtag today could be considered an uncompensated content creator for Twitter. Of course, the argument here gets a little bit muddy, as many people would consider the ability to widely share baby photos with their friends as an apt compensation for the work of, well, sharing baby photos with their friends. Better examples, though, come from internet companies that are much more brazen in their use of uncompensated labor to generate their platforms’ content. The Huffington Post is well known for boosting its content on the labor of unpaid contributing writers. The detailed maps that Google provides that we all know and use—for instance, for finding places to eat when visiting cities for academic conferences—are kept up-to date not by paid Google employees, but by legions of volunteers using their expertise of local areas to provide information and fixes via Google’s Map Maker editing service. And, inching closer to the world of gaming, Valve Corporation, the owners of the PC gaming storefront Steam, which sold at least $3.5 billion worth of PC games in 2015, employs around 350 people, none of whom work on translating games into Spanish—that particular function of the company, it was revealed in February 2016, is handled entirely by volunteers.[3]

Terranova simply termed this “free labor.”[4] Others have come up with catchier terms—Julian Küchlich, for instance, proposed the term “playbor” to refer to types of work done by internet communities that are pleasurable for those who pursue them, but also have the side-effect of adding value to a company’s product.[5]

Küchlich’s primary example is modding, the practice of technically-inclined players using the engine and assets of a commercially-released game to create a new game, one that is distributed for free online, but requires players to have purchased the base game in order to install and play it. (One of the main beneficiaries of modding has been the aforementioned Valve Corporation, whose eSports empire is based on the popularity of Counter-Strike and Defense of the Ancients, two mods that they were able to successfully acquire and commercialize as Counter-Strike: Global Offensive and Dota 2, respectively.) Today, we could add a whole host of gaming-related activities to the category of “playbor”—some of which look even less like traditional “work” than modding (which, after all, requires significant skills in level design). Gaming-related videos shared both through the video sharing site YouTube and the streaming site Twitch have exploded in recent years, with the result that a substantial amount of internet traffic at any moment is made up of people sitting at a computer and watching other people playing videogames—either live, as part of a stream on Twitch, or pre-recorded and uploaded onto YouTube. YouTube’s owner Google and Twitch’s owner Amazon have collected billions in ad revenue off of this content. And while success stories of game-playing celebrities circulate widely—including the astounding $15 million made by YouTube personality and newly-minted white supremacist darling PewDiePie in 2016—the truth is that most of these game-related content creators toil along making little or no money for their efforts.[6] For instance, Steven Bonnell, who streams on Twitch under the username “Destiny,” performs in front of his online fans an average of 60 hours a week, for a grand total compensation of $12,000 a year.[7]

Of course, the internet didn’t invent free labor. Uncompensated activity that generates billions in profits has been packaged and rationalized as a form of “play” for far longer than Google, Steam, or Twitch have been around. For instance, we can look toward the NCAA. Since its inception, the NCAA has insisted on the amateurism of its athletes—depicted in solemn, noble, and patronizing terms in the governing body’s bylaws: “Student participation in intercollegiate athletics is an avocation, and student-athletes should be protected from exploitation by professional and commercial enterprises.” In recent decades, however, public debate has erupted around whether these high-minded ideals are actually a front for the NCAA to rake in enormous profit on the backs of athletes who can never hope for any sort of compensation for their income-generating activities. Andrew Zimbalist called attention to the vast spoils of this uncompensated labor in his 1999 book Unpaid Professionals, and the issue has received increased attention in the wake of Taylor Branch’s 2011 cover story for The Atlantic, “The Shame of College Sports.” Branch accuses the structure of the NCAA as carrying “an unmistakable whiff of the plantation”—a charge supported by Zimbalist’s quote of former Louisiana State University basketball coach Dale Brown, who himself acknowledged: “This one-billion dollar TV contract is the paramount example of the injustices in the game. Look at the money we make off predominantly poor black kids.”[8]

“Participants in big-time college sports are all unpaid professionals,” Zimbalist writes,

“but paying them directly for their work on the school team is neither economically feasible nor socially desirable. A reasonable argument, however, can be made that the NCAA places too many restrictions on the top athletes’ ability to earn income off the playing fields. For instance, it makes little sense for schools to be able to sell memorabilia that exploit a student-athlete’s likeness and for the player to receive no compensation from related royalties.”[9]

It’s likely that the “memorabilia” Zimbalist has in mind here are things like jerseys and posters, but we should not forget another use of student-athletes’ likenesses: videogames. From 1993 to 2013, EA Sports held an official license to make NCAA-themed sports games, featuring the likenesses of current NCAA athletes in the sports of basketball and football (although usually not real names—the jerseys display only numbers). This license ended in 2013, a casualty of increased public scrutiny on the NCAA’s profiting off of the unpaid labor of athletes—here, taken to an especially creepy extreme, as the NCAA’s position seemed to be that they owned the very faces of their athletes, and that they alone could sell those faces to affix to the digital bodies that populate lucrative videogame franchises.[10]

Given the confluence of two different arenas where one frequently finds uncompensated labor, one might expect the binding together of eSports and college athletics that one sees at Robert Morris University to approach some sort of “nightmare scenario,” a perfect storm of exploitation, one that combines good-old-fashioned college sports with newfangled emerging media variations. Scandals such as the University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill’s use of “paper classes”—that is, classes for athletes that existed only on paper, and never met, in an attempt to bolster GPAs—have called into question whether the education that athletes are offered as their only “compensation” is a cruel illusion.[11] Meanwhile, China’s Jixi labor camp grabbed headlines in 2011 when it was revealed that prisoners were being forced to play World of Warcraft (Blizzard, 2005–), engaging in “gold farming”—that is, the collection of in-game resources that can then be illicitly sold to wealthy Western players with more money than time—for the personal enrichment of their guards.[12] Does the introduction of professional-level videogame playing into the world of University-sanctioned college sports represent the worst of both worlds? Are university administrators and athletics association heads sitting back and collecting League of Legends tournament prize money on the backs of inadequately compensated student-athletes?

Perhaps a serious investigative journalist could dig up more, but, from where I’m standing, the answer is “no.” Part of this is because Collegiate Starleague is, thankfully, not the NCAA, and Robert Morris University has—in my mind, admirably—shorn off the usual high-minded (and insidiously exploitative) rhetoric of amateurism as the defining attribute of college sportsmanship when it comes to its eSports student-athletes. Students are not paid directly for their athletic endeavors, but neither are the barred, NCAA-style, from receiving any remuneration in any activity connected to their (e)sport. Melcher reported that members on his team were free to travel around to local Chicago-area competitions with cash prizes, trading their RMU-honed abilities for compensation that may be meager, but is at least allowed:

“They do, here or there, travel to a LAN that’s local, or maybe it’s hour away. They’ll compete. If they win, they keep that. Which is outside of how colleges are used to, because you’re not supposed to get any sort of prizing off of your ability. But it’s not governed by NCAA, or NAIA, or something. It’s just how the community has answered a competitive question. I think they should be allowed to, you know, seek that reward. And it’s not—believe me—it’s not a lot of money. Maybe it’s $200 a kid, if they do really well. … I think we try to shove down traditional models of athletics, and how it works, on to eSports. It doesn’t fit. You just kind of … take what makes sense to the benefit of the student-athlete, I think, as sort of the first filter. And you leave the rest behind, and create something that fits.”[13]

So there is, at least, that. Robert Morris University is not pocketing League of Legend prize money, sneaking it away from the students who earned it. And—perhaps sadly—given the general state of college athletics within the U.S., that is something they deserve credit for.

The limits of optimism

This is not, however, to say that eSports represents some utopian future of college athletics, where the nerds rise up against the jocks, athletes are able to pursue compensation for their labor, and a new and serenely scandal-free variation on the “student-athlete” arrives to solve a wide swath of social problems. College athletics, for instance, has proved to be unable to douse the notoriously toxic culture of competitive online gaming. In his 2015 TEDx talk, Melcher speculated that the absorption of eSports into college athletics might carve out spaces free of harassment, where women gamers could finally feel comfortable enough to embrace competitive gaming. “I think that collegiate is the perfect environment for female gamers to come, and develop, and grow. Where they can play in the same environment. It could be the first true varsity co-ed sport.”[14] When I pressed him on this issue during our recent conversation, however, he came across as somewhat more resigned. “I’m optimistic about it,” he said, “but it’s a big hurdle, and a big challenge.” He happily reported that RMU’s program has been working with AnyKey, an organization that aims to increase diversity and inclusion within eSports, reiterating that he feels “like collegiate … sports is the perfect way to find out where [participation] is dropping off, what’s the problem.” But he’s a realist when it comes to the possible factors impacting eSports’ drastically lopsided participation rates. “I’m sure toxicity online is probably part of [it]. I don’t know if that’s the 100% answer why that’s happening. I kind of lean that way.” He also acknowledges the likeliness of college athletics being positioned too late in youths’ lives to make a real impact on women’s perception of the culture of competitive gaming. “My thinking is that it’s happening way earlier. Probably in high school. … I can imagine where, if you’re being attacked over your gender, as a 14-year old girl, you’re going to say, ‘I don’t need this. This game is not fun enough for me to have to go through this.’”[15]

This, of course, raises questions far beyond student compensation for “playbor.” With so much attention already cast on the role of college athletics within college rape culture, should schools really go out of their way to establish new varsity sports that arrive with a notoriously toxic and misogynist culture in tow. Sometimes, being the first just means that you’re the testbed for checking the viability of an idea that eventually goes nowhere. Melcher estimated that there are now 25 schools in the US competing through Collegiate Starleague that have officially recognized eSports as a varsity endeavor, and 18 that offer athletic scholarships. This is certainly not insignificant. He acknowledged, though, that most of the schools that have done this have been small—as Robert Morris University itself is—and that getting this sort of thing through a larger administration would be significantly more difficult. It remains to be seen whether such endeavors can effectively be scaled up to larger schools, with larger boards, and an unwillingness to pursue an eccentric project to raise their public profile.

And perhaps that’s for the best, because perhaps right now the smallness of such operations is what is keeping large-scale exploitation at bay. If nothing else, we can certainly say that things could be a lot worse for eSports in the academy than they currently are at RMU.

[1] Personal conversation with Kurt Melcher

[2] Kurt Melcher, “Gamers: The Rising Stars of Collegiate Athletics,” TEDxNaperville, 2015

[3] Alex Wawro, “Steam Spy: Last Year the Paid Steam Games Market Hit $3.5 Billion,” Gamasutra, 2016, “How a Whole Language of the Steam Translation Server Was Shut down – and Why It’s Important to You,” Reddit/r/Steam, February 9, 2016, archived here. (And yes, I am well aware of the irony of using Reddit as a resource when discussing free labor, given the unpaid status of its many moderators.)

[4] Tiziana Terranova, “Free Labor,” in Digital Labor: The Internet as Playground and Factory, ed. Trebor Scholz (New York, NY: Routledge, 2013). (This essay was originally published as “Free Labor: Producing Culture for the Digital Economy, Social Text no. 18 vol. 2 (2000): 33–58.)

[5] Julian Kücklich, “FCJ-025 Precarious Playbour: Modders and the Digital Games Industry,” The Fibreculture Journal, no. 5 (2005)

[6] Madeline Berg, “The Highest-Paid YouTube Stars 2016: PewDiePie Remains No. 1 With $15 Million,” Forbes, December 5, 2016.

[7] Jay Egger, “How Exactly Do Twitch Streamers Make a Living? Destiny Breaks It down,” Dot Esports, Dot Esports, (April 21, 2015).

[8] Taylor Branch, “The Shame of College Sports,” The Atlantic, October 2011; Andrew Zimbalist, Unpaid Professionals: Commercialism and Conflict in Big-Time College Sports (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999), 20.

[9] Zimbalist, Unpaid Professionals: Commercialism and Conflict in Big-Time College Sports, 53.

[10] For some details on this license—and how far EA Sports was actually allowed to go in identifying the represented players—see Joe Nocera and Ben Strauss, Indentured: The Inside Story of the Rebellion Against the NCAA (New York, NY: Portfolio/Penguin, 2016), 160–62.

[11] For the authoritative account of this scandal, see Jay M. Smith and Mary Willingham, Cheated: The UNC Scandal, the Education of Athletes, and the Future of Big-Time College Sports (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press Potomac Books, 2015).

[12] Danny Vincent, “China Used Prisoners in Lucrative Internet Gaming Work,” The Guardian, May 25, 2011, sec. World news. For more on the practice of “gold farming” and its ethnic association with Chinese players, see Lisa Nakamura, “Don’t Hate the Player, Hate the Game: The Racialization of Labor in World of Warcraft,” in Digital Labor: The Internet as Playground and Factory, ed. Trebor Scholz (New York, NY: Routledge, 2013).

[13] Personal conversation with Kurt Melcher

[14] Melcher, “Gamers: The Rising Stars of Collegiate Athletics.”

[15] Personal conversation with Kurt Melcher