Group presentation summary by Peter Forberg. This post will contain small spoilers for survival horror game The Forest.

The history of the Robinsonade is the history of shipwrecks: by boat, by plane, or by spacecraft, hapless travelers find themselves stranded on the shores, hidden beneath the canopies, or lost in the sands of some remote island or labyrinthian forest or sprawling desert. In this sense, The Forest (2013) begins much like any other transit disaster, sending the player crashing down into the trees of a mountain-lined peninsula with no other survivors—no other survivors except the player’s adolescent son, who is immediately pulled from the wreckage by a looming, naked mutant. And so, at the outset, The Forest announces that it is not merely a sandbox for enterprising colonizers, nor does it hide the fact that this brave new world is filled with dangerous mystery and lush with stories. Understanding that The Forest emerged during the survival-crafting game boom of the early 2010s, the developers needed a way to differentiate their game from the endless explore-mine-build games that followed Minecraft’s (2009) massive success. Thus, they took a different approach to the genre, with the director of the game Ben Falcone stating, “Our focus is much more on a survival horror experience, letting players experience being in the world of ‘The Hills Have Eyes’ or an 80’s Italian cannibal film” (Savage 2013). Seven years out of the initial alpha release, Falcone’s vision has been realized (with a sequel in the works), so what exactly does The Forest accomplish within this generic category; more specifically, how does it apply and subvert the tropes players will associate with popular survival games such as Minecraft or Terraria (2011)?

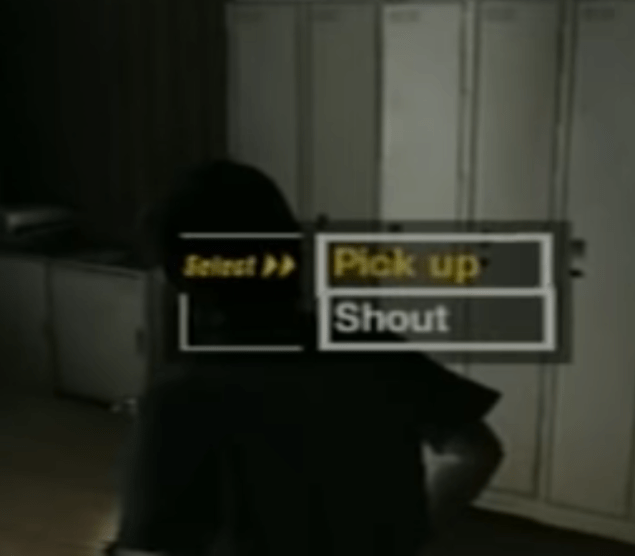

(Image credit: exceeding09 at

(Image credit: exceeding09 at