Ian here—

So, this isn’t a proper lesson plan. It’s just a quick cheat sheet. When teaching PlayTime, I pair it with Kristin Thompson’s chapter “Play Time: Comedy n the Edge of Perception” in her book Breaking the Glass Armor. (I consider myself incredibly lucky that I can pair one of my favorite films with a piece of writing that I consider to be one of the more astute and persuasive pieces of academic film criticism ever written.) My lesson, therefore, largely revolves around the conclusions of Thompsons’ analysis: that “the comic and the non-comic become indistinguishable” in PlayTime, and that the way the film “forces us into new viewing procedures” holds the potential to “successfully transform our perception in general.”[i] To view PlayTime, in other words, is to encounter a new way of seeing the world, one that might persist beyond the theater.

How do you successfully persuade students that PlayTime requires specific viewing procedures from its audience, ones unlike those we use when viewing a more traditional narrative film? My tactic is pretty simple: I pull student attention to moments that reward close viewing. Thompson herself lists a bunch of these in her chapter. I like to point to additional, different ones, so that I can show students new, unexpected visual rewards—therefore making both me and Tati seem smarter than we otherwise would! Please feel free to steal these.

1. Be sure to check your watch

Thompson spends two paragraphs detailing PlayTime‘s third shot. She makes some very astute points about how the couple seated in the lower lefthand corner of the frame have a pedagogical function: by explicitly pointing out things that they themselves see in the image, they demonstrate the very sorts of close viewing of seemingly innocuous detail that the film will require, and therefore prep us for the viewing task ahead. I agree with Thompson that this shot is remarkable, and serves as a sort of “key” for viewing and appreciating the film that follows.

Thompson, though, neglects to mention my very favorite moment in this shot—and one that I’ve found that students, upon repeated viewing, are likely to pick up on, in a visible “aha” moment. This is fine, as it gives me something to point out that wasn’t in the reading!

Thompson notes that, at a certain point, the shot’s action shifts from the couple simply pointing things out, to Tati beginning to experiment with the soundtrack, setting up image-sound gags. She mentions how the cry of the hidden baby makes us momentarily associate the towels the cleaning woman is carrying as a baby. But she doesn’t mention something that happens just a couple seconds later: At the very moment the officer glances down at his watch, the wife asks her husband if he’s checked the time. This line is rendered as, “Are you sure you checked your watch?” in the version of the soundtrack in which these characters’ dialogue is dubbed into English. (As you can see below, it’s a little bit different in the French, but close enough.) In either case, the effect is the same: there is a “match” between the dialogue and the action onscreen, one that cannot be explained in terms of one character influencing the other, but instead serves as a wink on Tati’s part, acknowledging his complete control over sound and image, and encouraging us to keep looking out for off-kilter sound-image relationships.

2. Oh, to know your faux Hulots

The presence of false Hulots in PlayTime (I prefer the term “faux Hulots,” because, honestly, who wouldn’t?) is something that’s remarked upon in the Thompson chapter, but not fully catalogued. It would be embarrassing if someone proved me wrong here (although I would welcome the correction), but by my count there are six distinct “faux Hulots” in PlayTime. The first faux Hulot is the most famously fiendish: he shows up in the airport, before we ever see the real Hulot, meaning that plenty of viewers will mistake him for Hulot’s first appearance in the film.

We see this Hulot first by in the customs checkpoint, where a woman calls out to him from the bar (you can see her standing on her stool on the left side of the frame in the first image), again by the escalators (where he loudly drops his umbrella, momentarily causing everyone in the frame—and, presumably, in the audience, as well—to stare at him), and then again outside. (Originally, I wasn’t sure if all three of these were the same faux Hulot, but then I checked the socks: a dead giveaway.)

Outside, the woman who first signaled him from the bar finally catches up to him, and tries to get his attention, thinking that he is Hulot. When he turns around, he reveals that he is not, and is quite perturbed about the mistaken identity. This shot is a reveal, but nestled within it is another gag: since the time we saw her last, the woman has donned a trenchcoat and picked up an umbrella, meaning that she actually becomes our second faux Hulot!

The first faux Hulot makes his last appearance in the shot that marks the first appearance of the real Hulot. There is a moment of the “passing of the torch” from the imposter to the real Hulot, as their umbrellas get tangled up.

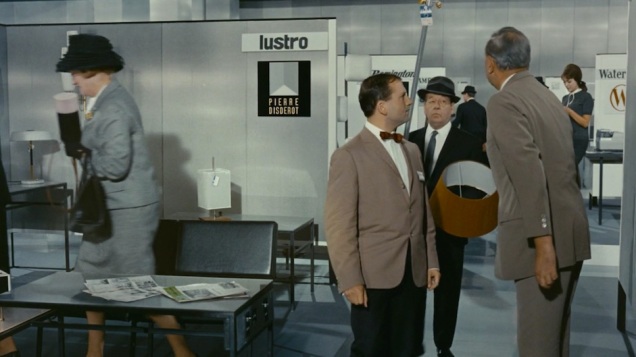

Is the film done with faux Hulots, though? No! More are sewn through the show. Our third faux Hulot makes his appearance at the expo, rifling through the papers of the “Slam You Doors in Golden Silence” booth—an act which the real Hulot later gets mistaken as the culprit for.

Monsieur Giffard, the businessman with whom Hulot was attempting to meet at the office building, falls prey to our fourth faux Hulot. Excited by the prospect of finally catching up with Hulot after a series of escalating missed connections, Giffard breaks his nose on an invisible glass door, and all for naught: this “Hulot” is just a goateed businessman, who just put on his hat and trench coat moments ago.

The broken-nosed Giffard is still pursuing phantom Hulots come evening, when he runs across the film’s fifth faux Hulot (and first Black Hulot). Attentive viewers will piece together that our real Hulot is actually still riding the bus at this time.

After Giffard finally catches up with Hulot by chance (fascinatingly, at the 1 hr 2 min mark—the end to this drawn-out, stop-and-start chase scene occurs at what is almost exactly the halfway point of the film, at which point we transition to the Royal Garden), faux Hulots drop out of the movie for quite some time. The last one shows up at the film’s end, when Hulot is stuck in the supermarket and can’t deliver his parting gift to Barbara in person. He asks a passer-by to do it for him, instead, and, as luck would have it, he chooses as his avatar the film’s sixth and final faux Hulot.

3. Follow the foreshadowing

This is just a brief point, but once you’ve seen the film a few times, it becomes easy to spot the fact that, despite its crowds, the film doesn’t actually have that large of a cast. Many people that we see in one location show up in other locations, and are even signaled to be the same character, given their dress or their props. Watching the film over and over again, you can begin to get a sense of their stories, their route through this city that brings them into contact with Hulot.

Sometimes, this means that you’ll catch tiny bits of foreshadowing of future jokes. For instance, many viewers won’t notice man whose lamppost causes so much confusion on the bus until that gag is already in full swing. He is, in fact, in the film earlier, though, appearing with his lamp already in-hand at the expo. Perhaps he bought it there? I haven’t been able to scan every shot thoroughly for this kind of detail, but my money’s on there being more instances of minor characters that have maybe one gag in the film showing up in the background in other locations, as well.

4. Keep your eye on the cutouts

The presence of black-and-white cardboard cutouts as stand-ins for extras in the backgrounds of shots is another well-known aspect of PlayTime, and another thing mentioned by Thompson in her chapter. Even if students catch the cutouts, though, what’s often missed is that Tati actually sometimes gets his flesh-and-blood extras to behave as if they were cutouts. This creates an extra perceptual game for keen-eyed spectators: sometimes, when you think you’ve spotted a cut-out, what you have in fact spotted is an unusually still extra.

For example, this shot of the tour group in the airport features three cutout figures near the window in its background. (From here on in, red arrows will indicate cut-outs, and green arrows will indicate real actors.)

Earlier in the film, however, in the third shot, these cutouts were “played” by real actors—the movement of which is so sporadic and subdued as to make them virtually indistinguishable from the inanimate objects that eventually replace them.

When Tati gazes down at the sea of cubicles in the office building, cutouts and real extras intermingle freely. About half of the cubicles are populated by cutouts, and at least one includes a flesh-and-blood extra and a cutout as cubicle-mates. The back of the left and right aisles are populated by two couples: a live actor converses with a cutout woman on the left, while a live actress converses with a cutout man on the right.

If we return to the shot in which Giffard breaks his nose, we see an especially weird trick. To the extreme right of the frame stands a cut-out. Just to the cut-out’s left, though, is a flesh-and-blood actor, standing completely still, paused in mid-step. Throughout the action of the shot, he remains completely frozen, looking as much like a cutout as a human being possibly can look. It is only in the shot’s last seconds, after Giffard has hit his nose and subsequently vacated the frame, that he “comes to life,” slowly leaning forward until he adopts a normal gate and walks nonchalantly away.

5. Always look everywhere in the Royal Garden

I’ve seen PlayTime six or so times at this point, including twice on 35mm and once on 70mm. And yet there are still many gags I’ve read about in the Royal Garden sequence that I’ve never managed to see, because I’ve been looking in the wrong part of the frame. (It was only once I saw the film in 70mm that I finally caught the moment where Schultz orders his meal by pointing at the stains on his waiter’s coat.)

I do my best, though. When discussing this sequence, I usually focus on the role that dancing plays, especially once the second band starts its set. Once it does so, the frame tends to fill up with dancers, making the film more visually chaotic.

Many of the gags during this segment of the film have to do with the way in which those characters who are still trying to do their jobs, fulfilling their socially-expected duties, have to navigate the explosion of anarchic energy (of pure paidia, we could say, following the implications of the film’s title) that is thoroughly disrupting the rules of this world. The most obvious example here is the waiters. I’ve noticed the waiters hopelessly trying to brave the swirling sea of humanity on the dancefloor in this shot many times before, but I think it wasn’t until my most recent viewing that I noticed that there’s one waiter who tries to bypass the crowd by crawling up on the stage with the musicians, awkwardly jockeying with them for space.

But it’s not just the dance floor that’s populated by dancers. I point out to students that, as the second band’s set goes on, we start to see people dancing in every corner of the frame, even in areas of the restaurant far removed from the dance floor. In the background to the right of this shot, for instance, the energy of a dancing group of women proves infectious, and a young waiter briefly joins in, plate still in-hand.

The explosion of dance beyond the dance floor continues in this next shot. Patrons by the bar bop up and down with the rhythm of the music, while the woman crossing the foreground of the frame prances wildly. When showing this clip, I argue that we’re not just seeing dance for the sake of seeing dance here. Rather, the eruption of dance in these unexpected and unsanctioned spaces is part of Tati’s overall agenda of getting us to aesthetically re-appreciate the objects and gestures of everyday life. After all, what is the halting stumble of the intensely drunk man in the black suit (seen here to the left of frame) but a kind of dance?

The same applies to the graceful fall of the blue-suited drunk off of his stool, later in the same shot:

Well, that’s all I’ve got for now. Keep your eyes peeled, and have fun!

[i]. Thompson, Kristin. “Play Time: Comedy on the Edge of Perception.” In Breaking the Glass Armor: Neoformalist Film Analysis. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988. Pg 261.