While “immersion” is often considered the ideal tenet of modern videogames, the unification of the player and avatar on a physical, kinaesthetic level is a generally overlooked aspect of that goal. Players are rarely asked to consider their own body as a controller, aside from their fingers (or feet, occasionally). What new games could be created, simply by implementing mechanics with the player themselves in mind? Asphyx, a Flash game created by Droqen, takes the universal bodily experience of breath and makes it crucial to its gameplay in an attempt to simultaneously merge game with reality and force a greater acknowledgement of one’s own experience of playing.

Asphyx presents itself as a straightforward two-dimensional platformer, a format instantly recognizable to a vast majority of the game-playing public. The game’s pixel-art graphics and low-detail spelunking draw on a long history of titles, perhaps the most recognizable being Super Mario Bros. Players are instructed by Droqen to use the arrow keys to move side to side and to jump — also useful for jumping is the X key — and that is virtually all one needs to begin. This ease of gameplay as well as the game’s original publishing in Flash as a browser game meant that Asphyx was a highly accessible title upon its release, insofar as it was simple to comprehend and to begin playing on the Internet. It is one artifact amongst the legions of similar Flash browser games created in the 2000’s and early 2010’s that were simple to pick up, comprehend, and move on from. Though, if Asphyx was so straightforward a game there would be no real merit in dissecting it as I am about to do. Droqen implemented one crucial mechanic (though more like a house rule) into Asphyx that sets it apart from games of its time and caliber: when the player is underwater, they are instructed not to breathe, in real life.

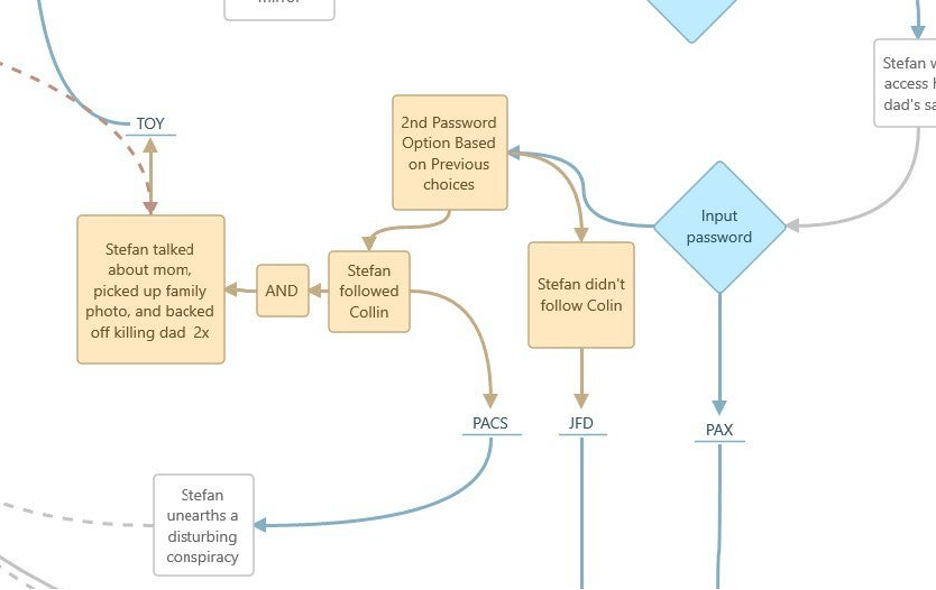

A thorough explanation of Asphyx’s breath rule is crucial to understanding the project of this game, and the experience that Droqen is attempting to simulate. Addressing the player directly, environmental text in the earliest section of the game (see above) declares: “WHEN YOUR AVATAR IS UNDERWATER, YOU MUST BE HOLDING YOUR BREATH. PRESS ESC IF YOU FAIL. YOU FAIL BY BREATHING IN, UNDERWATER.” Water, represented by a lighter purple color, is everywhere in this cave system. Its manipulation and traversal is the essential challenge of the game, which the breathing rule adds a layer of bodily difficulty to. Though, this system has a caveat that makes me hesitant to call it a true “mechanic.” There is no implemented measurement of the player’s breath, nor any punishment for not following the rules in real life. Essentially, Droqen is leaving adherence to the rules up to the player. “IT’S UP TO YOU TO FOLLOW THE RULES… OR TO NOT, BUT I PERSONALLY THINK YOU SHOULD TRY,” the disembodied text explains.

While there are no punishments for not following the rules, there are no rewards present in the game, and no stated goal to the exploration that the player undergoes. All that they encounter is a series of empty rooms typical of a platformer, and some simple obstacles involving buoyant blocks that must be moved with water to progress. While one would think that the breath rule would completely shift the requirements to succeed at this game, the player need only hold their breath for a few seconds, at least in the first part of the game. Pressing the escape key at this point returns the player to the moment before they entered the water last.

At a certain point the player will happen upon the second section of the game, in which the caves are being continuously flooded with water with no way of draining it. Asphyx then becomes a race against time, to get as high as possible to escape their drowning. However, Droqen’s level-building actually makes it impossible to escape the water permanently, as platforms fall when stepped on, causing a long fall into the depths of the cave. Even if the player does find a pocket of air, there is nothing more to explore at this point in the game; they must press the escape key, at which point they make it to the ending levels, now being “worthy.”

So, why is Asphyx so fixated on breath? What does it aim to explore with its unique rule, and exploration of bodily functions? If the game refuses to actually verify that the player is following its set rules, then what is the point of incorporating them at all?

To answer the first few of these questions, I wish to draw on and extrapolate Melanie Swallwell’s theory of “becoming,” as well as Brendan Keogh’s identification of “embodied literacy.” In her essay Movement and Kinaesthetic Responsiveness, Swallwell writes about the experience of reacting with one’s own body to movements, sounds, and sensations from the gameworld. It is a well-known phenomenon that some players will react, emphasize, or otherwise feel things in their real bodies while focused on a game, as if their virtual avatar and their physical form were linked. Swallwell mostly discussed high-intensity, motion-centric games like Quake II and Grand Prix Legends, and how players will either be affected by the game’s movement mechanics or project their lived experience onto the game. She writes: “Though (sadly) I don’t usually get around in a vintage Porsche, I do know the sound and feeling of gear changes and the way that one is thrown around within a car by hard driving […] While my physical response to the sound of Grand Prix Legends was a surprise, the game was not introducing me to anything new.”

Part of Asphyx’s project is to induce this kinaesthetic response within the player, albeit on a smaller scale than the powerful sensations that Swallwell discusses. By limiting the player’s breath, the author seemingly hopes to induce frustration, annoyance, fear, and some level of panic (particularly in the final flooding section) by drawing on the universal human experience of not being able to breathe when wanting to. It also hopes to counteract the usual “flow state” of gameplay that typifies Keogh’s “embodied literacy.” As he write in A Play of Bodies: “The literate videogame player […] has a basic understanding of the performative grammar of different videogame genres […] and is able to transport and adapt this literacy from one videogame to the next.”

Asphyx, as an easily understood game for a literate player, distinguishes itself from the norm by incorporating its unique breath mechanic, working against the usual understanding of embodied literacy. Rather than merging the avatar and the player, the text of the game’s minimal narrative always distinguishes between the human at the screen and the controlled character. By often referring to the player directly, and telling “you” to think about your own breathing, Asphyx essentially forces a simultaneous physical unification and separation of the avatar and the player’s body; they both “breath” at the same time, but the player is also encouraged to be aware of their own body. At the end of the game, the player is told to “judge themselves,” and ask if they are worthy of truly “winning,” though it is mechanically impossible to do so.

In creating Asphyx, Droqen tested the limits of what immersion in games is. The game is seemingly paradoxical, as it asks for a level of bodily identification with the avatar — something rare in games even a decade later — while simultaneously instructing the player to think about and judge themselves and their physical experience. It combines aspects of Swallwell’s “becoming,” while trying to avoid the deeper ramifications of embodied literacy as defined by Keogh. In the years since Asphyx’s release, the world has seen games that place less trust in the player, or do seek to create the flow state that embodied literacy necessitates. Before Your Eyes actually tracks player blinks, merging to a remarkable degree the player and the game’s character. SUPERHOT VR does the same, creating a flow state in a VR world that can be easily understood by even the newest gamer, as long as they can look around. With these new horizons on both sides of the spectrum, Asphyx’s place is awkward, as a middle child that plays with both. Yet still today, the question of breath is left largely unexplored, possibly due to its accessibility issues and health hazards, while movement and other physical activities are gamified. What new frontiers in game immersion would there be, if the world were to follow Droqen’s lead?

-Leo Alvarez