By: Miles Rollins-Waterman

File://maniac is an excellent game with more than a few flaws. First and foremost, I found the game to be too simple. It lacked a certain depth and width that I believe could have elevated the experience to a significant degree. Second, the game, in my opinion, holds the players hand too tightly, and could benefit from more dead ends and false paths. Finally, and I’m actually not quite sure this should be counted among my criticisms, as it’s more of an observation, but I don’t believe this game deserves the title of “detective” game. Another way to put it I suppose would be that file://maniac is not a successful blend of the detective novel genre and video games, but to be clear, I don’t believe this failure detracts from the quality of the experience, just the lens through which we ought to view it.

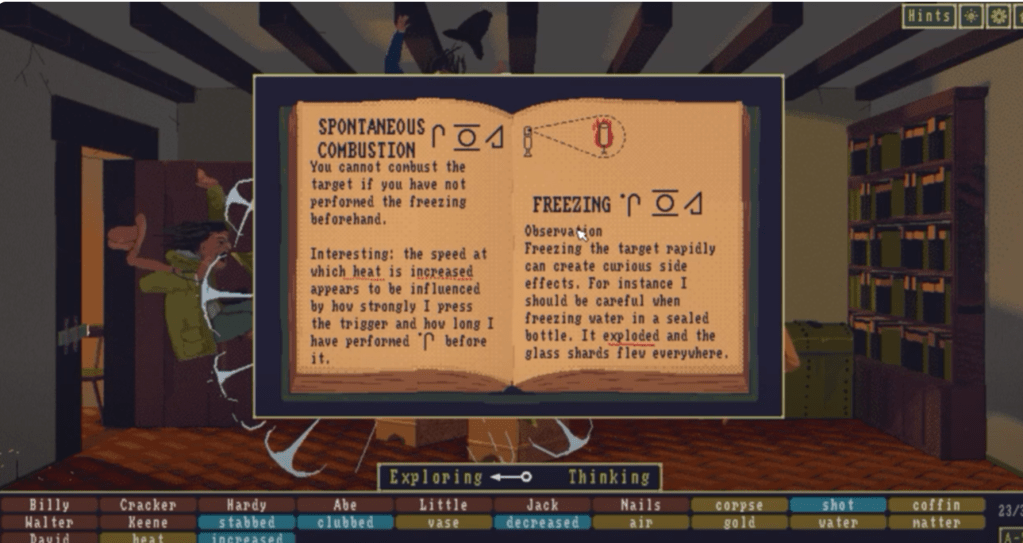

I’ll begin with its simplicity. On face, the idea of digging through indexes in File Explorer as a way to interact with the game world is fascinating. It’s a medium of play I haven’t encountered, and the way it was handled in this game was close to perfect. But I think it could stand to be more difficult. As strange as this is going to sound, I would have preferred if navigating the game files was just as arduous and time-consuming as the puzzles themselves. Granted, there is a thin line here between a beneficial amount of extra challenge, and a bloatsome amount, but if correctly navigated it could be a huge boon to the quality of the experience. For instance, there could be a part of the game where the File Explorer breaks temporarily and the player is forced to use archaic command line tools to continue the story and perhaps repair their original medium. Maybe certain puzzles could require accessing files that are scattered across the user’s machine, and not just localized to the game folder. Even small additions like these could have pushed the limits of the ingenuity of this concept, a push that this game desperately needed.

To take this simplicity critique further, I’d ask that one try to conceptualize what it means to alter a game’s files. Acknowledging that the reader of this post may not have played the game, think about what this would look like to you. For my part, when I first heard that this was the game’s main mechanic, I was thrilled. To me it represented endless possibilities for creative workarounds and clever backdoors. I envisioned being able to find solutions to the puzzles that the developers themselves hadn’t necessarily considered, and being able to chip away at the game’s challenges with my own brand of intelligence. Harkening back to the maze discussion we had in class when talking about The Name of the Rose, I suppose I pictured the developers dropping us into a maze and giving us a sledgehammer; so we might smash our own path to the center. Reality is often disappointing. Although diving through files, rewriting, moving and deleting them, was the game’s major focus, I felt it was missing the space for wild innovation I had imagined. We were given this fun and expressive medium through which to experience the game, yet we were confined to the path the developers had laid out for us, with no actual mechanism by which we could circumvent the narrative. Our phasers were set to stun, so to speak. To give a concrete example, the very first puzzle of the game involves deleting a “door” file from the game’s directory in order to open a locked door in the game itself. Once the file is deleted, your character can open the door and continue the game. I love the fact that deleting the door file actually affects the door in the game world, but I am baffled that it was executed in such an appallingly basic manner. The file is just sitting there in the main game directory. The player doesn’t need to think or struggle to find it. They don’t need to consider where a door file might be, and use some form of deduction or logical path to get to the answer. It’s provided for them on a silver platter.

This critique about simplicity folds nicely into my second point about difficulty. Simply put, the game is too easy. The answer to each and every puzzle is quite literally spelled out for the player, and although it is done in an interesting fashion on one occasion, 99% of the other puzzles are akin to reading instructions off a page and then carrying them out. When dealing with something so seemingly volatile and powerful as editing game files, one would expect a degree of volatility and power, and yet. More to the point, it is quite impossible to fail at a given task. Not only because the instructions are written out for you or because of the looping nature of the game, but because the developers didn’t take their idea far enough. When I think of modifying game files, I think of something a little dangerous. I think of the danger of corrupting your save, and having to start again, or deleting/misplacing something vital to the game. Things that have concrete consequences. It feels like the developers have baby-proofed (or maybe idiot-proofed) this tool for their players, and in doing so have taken away much of the gravitas and intrigue that they garnered by including it in the first place. As I mentioned earlier, many of the puzzles are criminally simple, and while a few like these are important to allow the player to get their feet wet and feel a sense of accomplishment, a game filled with nothing but left me at least feeling unfulfilled. This simplicity or “hand-holding” as I called it earlier makes the game experience far less rewarding in two ways.

Firstly, the sense of accomplishment one feels after completing a puzzle is, in my opinion, greatly diminished by their difficulty or lack thereof. While it is cool to see my deleting or renaming a file have in-game consequences, it doesn’t feel so good that I only did those things because it was explicitly spelled out for me. Second, it chokes out the feeling of freedom one gets from the actual act of editing game files. I’ve already talked at length about my expectations and how they weren’t exactly met, but I can’t understate how neutered this game felt to me on my first playthrough. The developers are giving us this tool that is supposed to be potent but dangerous, and yet we get neither. It’s as if they are giving us a sandbox to play in, but we can only build our little sandcastles in the 5ftx5ft section of the box they allow us to operate in. It’s frustrating to say the least. I should be able to break the game, whether by accident or on purpose, in my pursuit of the truth. I should be forced into dead ends, such that my only option is to carve a new path forwards through the fabric of the game. I would like to feel as though me and the developers are at war, with them creating a complex world for me to try and tear down, and me hacking away at what they’ve built for me with gusto. Instead, I feel like a gradeschooler who’s teacher is leading them by the hand through a museum, where they are allowed to look all they want, but never touch. Where the only path forwards is where the grown-up says to go. I think this final point is exacerbated by how the developers chose to implement this deep dive into the game files. It feels very sanitized and structured. They’ve given us this idea that we’re doing something taboo and illicit, but it’s very clear that everything has been laid out for us in such a way that we couldn’t do anything destructive if we tried. The “game files” we’re editing seem to be in a cordoned off section from the rest of the game’s innerworkings to ensure that we can’t really break anything. The most “searching” we have to do is switching between one folder and another, and almost every time the folder the file you need is in is given to you, without you having to lift a finger.

My final critique, if you can call it that, moves away from loftier ideals and concerns the actual execution of file://maniac as a gamification of a detective novel. My position is quite cut and dry in that I don’t think it is one, or if it was intended to be one, then it fails spectacularly. There isn’t really much detecting that goes on in the course of the game, and I’d label it more as a series of puzzles than a proper narrative of detection. Most of this stems, I believe, from the games simplicity and rampant babying, which I already discussed at length. After all, there isn’t much to detect when most everything is written up for you. More than this though, file://maniac doesn’t offer the player any kind of narrative whatsoever. It is a short game to be sure, but even in brevity there is room for exposition and storytelling, neither of which the developers endeavored to accomplish. As a result, this game felt much more like a proof-of-concept or a demo for something larger and richer, narratively speaking. It really was just a series of puzzles set to mysterious music and with some light graphical and point-n-click elements. If that’s all the developers intended, then my previous criticisms aside, they’ve hit the nail on the head. Yet I can’t help but wonder if they could have done something more.