By Elle Thompson

(Disclaimer: This post is based on my perspective on a play-through of Obra Dinn. I realize that others might solve/think about solving the mystery differently so take this as more of a take-away post than a generalization about the game at large.)

The Return of Obra Dinn, though a complex mystery, is largely a game of well-informed guess and check. The player’s primary agency and interaction with the investigation is through observation and deduction. The pocket watch allows the player to step into the memories of the deceased former crew of the Obra Dinn and relive still frames of their last moments. Through these memories, the player is expected to ascertain “the identity and fate of everyone aboard.” And although the game provides the player with a wealth of clues, many of them are obscured, and only accessible through a Sherlock Holmsian level of niche observation on the character’s actions, words, whereabouts, and appearances. With sixty identities and fates to solidify, the game would be all but impossible without a confirmation system.

The confirmation system in Obra Dinn comes in sets of threes. The player must correctly identify three individuals’ names, fate/cause of death, and sometimes the responsible party for their deaths. All three details within the journal entry must be correct before it counts towards a correct identity. A name can be correctly matched but if the fate or cause of death is wrong it does not count towards the three cases needed, and vice versa. However, once the player is reasonably confident in at least two of these identities or narrows their pool of identities, it becomes easier to abuse the system and guess and check names and fates until they receive a “Well Done” notification from the system.

This produces a level of confirmation bias that seems antithetical to the mechanical intention of careful observation and deduction carried throughout the game. To illustrate this juxtaposition it is important to take a close look at the clues and methods of deduction actively encouraged by the game to deduce the identities of the “unknown souls” and their “unknown fates.”

Unknown Souls

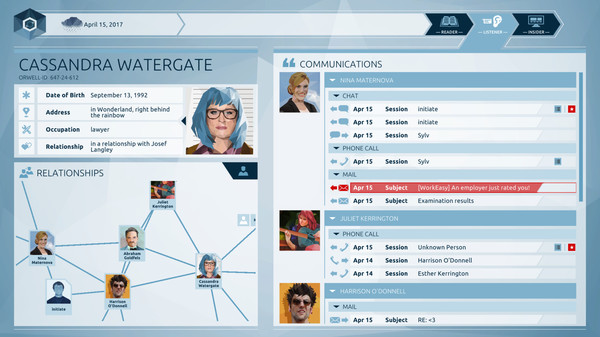

There are sixty names on the crew manifest. Each of those names has a corresponding occupation and country of origin listed.

The occupation can often be a helpful clue when observing an individual’s actions on board the ship. For example, there is a scene in which Huang Li, a topman, is killed by a lightning strike when climbing the ship’s rigging. It stands to reason that the others who have climbed the rigging with him are also topmen and therefore narrows their possible names as well as their location in the crew sketches (conveniently crew of the same rank tend to stand together). The sketch is also a helpful resource for consulting crew uniforms and matching like crew members with already identified members of the same occupation.

The same trick can be used for the country of origin a little less subtly. The Formosa nobles, for example, have their own labeled section of the sketch titled “Formosan Royalty.” Therefore any crew picture that matches those four faces is of four names marked as Formosan in the Manifest. Audio Queues can also be used to differentiate between crew countries of origin, as some crew members converse in, exclaim in, or translate for other languages. A quick Google search of the transcribed dialogue can match a crew member to a country and therefore narrow down or completely solve the crew member’s identity based on the manifest.

Unfortunately, this narrow and direct correlation between race, nationality, and identity can lead to pretty blatant profiling in order to deduce identities. For example, there are four Indian seamen, two of whom get sick and die from illness, two of whom are crushed to death. Only one character is named in dialogue “Syed,” and the rest are never named out loud leaving the easiest course of action to cycle through their names with the crew members identified speaking to him in Hindi.

Similarly, there is little to no differentiation between the Chinese crew members, who are identified in the scene by looking vaguely Asian and serving as translators for the Formosan nobles. The four Chinese crew members are all topmen, and all have little to no plot relevance, leaving the simplest course of action to cycle through their names with the Asian characters from the sketch.

It is also relevant to note that both the sets of Indian Seamen and Chinese Topmen deductions are structured like dominos. If the player correctly identifies one or two of these characters, it stands to reason that the only other Asian or Indian-looking faces in the sketch must belong to the remaining names. This imparts some degree of flippancy in the deduction of these groups and rewards race-based deduction instead of proper investigation into these characters’ identities that other characters (namely Europeans) require.

(Disclaimer: According to the Wiki there are other ways of learning these crew members’ identities such as matching their bunk numbers to their shoes. However, considering the pixelation and similarity of the niche outfit cues, and the explicit correlation between race and identity, the point still stands.)

Unknown Fates

There are 24 fates, or causes of death or disappearance, that can be matched to those names. Some of these fates have sub-fates, such as “Shot” which has the subcategories of “canon,” “gun,” and “arrow.” Some of these fates will not be matched to a cause of death at all, and some are used multiple times. All of these fates rely on mostly visual cues to deduce the manner of death by identifying a weapon or attacker. There are exceptions, like illness and environmental hazards, however, those are also heavily reliant on visual observation of the scene.

Although some deaths are simple to deduce, such as the Kraken/beast tearing a man in two and spilling his pixelated guts, others are purposefully or unfortunately obscured. For example, during “The Doom,” chapter, the player must deduce the fate of several characters who were thrown overboard by inferring when they are present in one scene and not the next. This is difficult but not impossible given enough attention and backtracking through the memories. Less intentionally obscure, however, is the fate of characters like Bun-Lan Lim who was clawed to death by a “beast.”

The clawing part, however, is up for debate as seen in the image, it is incredibly unclear what the beast is doing to her (biting? eating? poisoning?) nor does it necessarily look fatal in comparison with other fates in the same boat as her (speared, drug overboard). The other Formosan noble, It-Beng Sia, meets a similarly confusing fate as he “burns to death” after opening a chest. The pixelated and monochromatic art style leaves both of their deaths unclear regardless of deduction prowess and effort. The only way to deduce either of their fates is through a process of elimination and testing with reasonable confidence in two other individuals’ fates. This leaves the player to rely on abusing the confirmation system blindly instead of relying on the visual evidence presented.

Guardrails

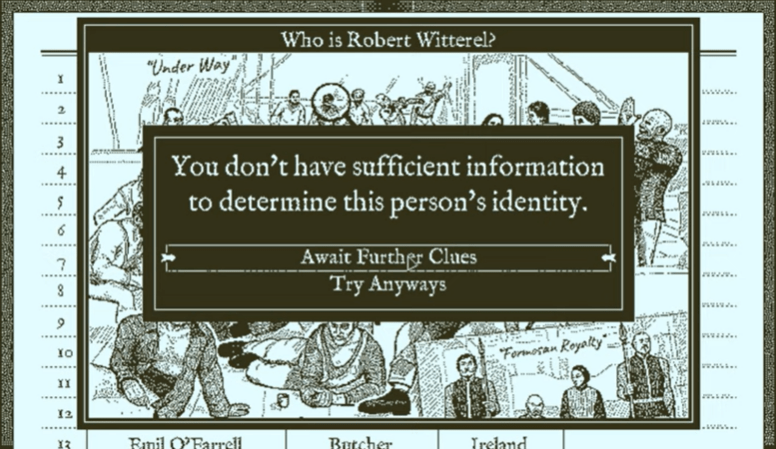

However present the instinct and reward of confirmation bias might be, there are some guardrails put in place by the game to discourage random guessing and impulsive deduction. For example, when a player attempts to identify a character, whether it be based on generalization like in the case of race and nationality, the process of elimination like in the case of pixelated graphics, or other shortcuts, the game will warn them against guessing without proper information.

This is more of a discouraging attempt than a hard stop as players can still select “try anyways,” but the passive aggressiveness of that diction suggests that the player is attempting to play the game in a way the developer did not intend but is willing to tolerate.

The game also implies at multiple points that there will be times, regardless of the player’s investigative prowess, when they do not have enough information to make a solid identification of all the individuals. While not as direct as the previous example, this implies that the player should try their absolute best instead of getting roadblocked or resorting to desperate methods. Instead of giving in to random guessing players can work with the evidence they have and revisit the memories with new insights.

Takeaway

Overall The Return of Obra Dinn, while seemingly at odds with itself mechanically, does a decent job of discouraging guess and check confirmation bias through these guardrails and the sheer volume of information players are asked to sift through. After all, it would take as much or more time to guess through 60 names than to pay attention and carefully sift through it with an investigative eye. While I have my complaints and criticisms as detailed above, they are not game or immersion-breaking at any point and it is still a fantastic example of investigative fiction that asks the player to step into the detective’s shoes without handholding.