By Will Traband

Orwell starts with the mundane. You open the game and get a login screen, as you would on any website. The credentials you give are your name for the game, but it still feels like any other login screen. When we played it, we did not take this very seriously and made a name that is, shall we say, inappropriate. This moment is the key to why Orwell is effective, but it will take some time to understand why.

The game thrusts you into a place labeled Freedom Plaza plaza, or rather, a hidden camera spying on people there. As you watch people go about their day, little biographies about them pop up. One person is unknown to the system, but the program notes one lady as having previously had an altercation with the police. A couple sits together on a park bench. Then, the bomb goes off. Your job is to find the culprit, and the entire game takes place on your work computer, through cameras and the internet. However, notice that the game has primed you in two ways. Firstly, the game took its time to propagandize you with the best of The Nation. It portrays an idyllic plaza to you and highlights the innocents who died in the blast. The game leads you to feel bad for the people who died and distracts you from the authoritarian regime. Secondly, Orwell shows you a lady with a rap sheet. She is lead number one, and you are led to suspect her despite little to no evidence.

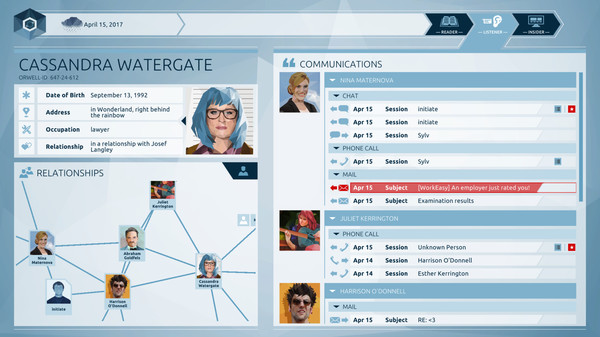

Suddenly, you see an office interface and an adviser talking to you. Your job is to find who did this using a new program called Orwell. Immediately, the game starts getting you used to the software, and once again, everything is mundane. It feels like office training, not preparing to invade people’s lives. Orwell is fundamentally about sorting through files and finding connections, which makes it easy to forget that the premise is that you are spying on people. As we played, we found it easy to make fun of characters. Interestingly, it made us more amenable to The Nation. One lady looked like the stereotype of blue hair and pronouns. Another guy looked like a standard rebellious musician. Since many of us playing could fit some of those descriptions, it was easy to laugh. I, for one, made several jokes about how anything The Ministry of Truth says must be true. Investigating this woman named Cassandra Watergate felt like office snooping, not wiretapping her phone and listening to the details of her personal life. We gossiped about her love life while putting together the information to put her in jail for the rest of her life.

Orwell is just a game, of course, but it actively dissuades you from taking it entirely seriously. It puts pressure on you in the form of another bomb threat, but everything about the interface screams office worker. Now that you have the correct mentality, meeting your goals feels better. Only after you prove Cassandra is guilty of her previously accused crime are you hit with a dose of reality. A scene occurs where your adviser interrogates Cassandra and reveals they have information from private calls to arrest her. She swears and feels violated by the intrusion. I realized then that I would feel the same way. Although she is only a game character, and I had embraced the position of the bad guy long ago, I still was left with a bittersweet feeling. However, I still had work to do, so I left those feelings at the door.

Orwell is masterful at manipulating you. It gives you a familiar interface, like social media and internet browsers, but lets you do horrible things with them. That moment I mentioned earlier highlights this perfectly. We messed around and put bad words into our video game name, and in the process, we took the gravity of our actions less seriously. Orwell feels so mundane that it becomes routine when people suffer directly because of you. The game makes you feel as if they deserve it anyway. Cassandra hit a police officer with a rock when he tried to arrest her friend. Her friend expresses gratitude for being saved and calls Cassandra a hero. The game tells you the officer had a broken skull and had to go to the hospital for weeks. We could spend hours discussing whether or not her intentions make up for her actions, but the game makes you sidestep all of the philosophical discussion. You must find the data to arrest her since it is your job. There is no place for nuance in The Nation, and once data is in Orwell, it must be acted upon.

Orwell presents an interesting dichotomy between the normality of office work and the oppression of an authoritarian regime. It sets itself up with propaganda to make you sympathetic to The Nation and has characters from groups of outcasts, so you empathize with them less. Even though you recognize the blatant propaganda, the unsubtlty makes it funny. Then, despite the heavy nature of the topic at hand, the game makes spying on people feel routine. It makes the consequences for those you spy on feel less severe and emphasizes your impact on The Nation. Sure, you are trying to stop another bomb from going off, but once you do, your adviser tells you to go home and get some rest. You are left with no time to wonder if the ends justify the means. After all, you still have work in the morning.

Photos from: https://store.steampowered.com/app/491950/Orwell_Keeping_an_Eye_On_You/