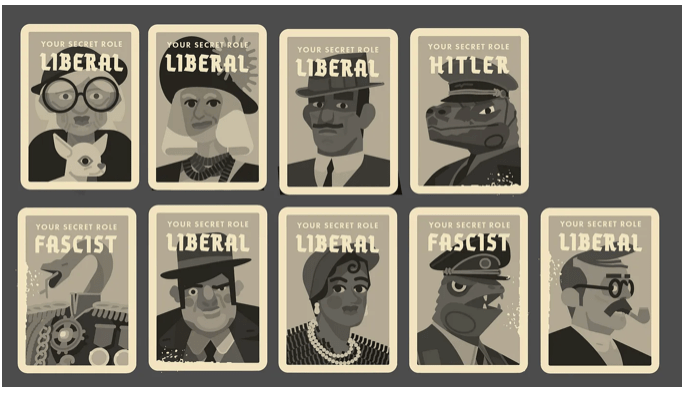

When it comes to social deduction games, Secret Hitler is often considered one of the staples. The premise is simple: if you’re a Liberal, stop the Fascists and their Fuhrer from gaining power and influence; if you’re a Fascist, do what you do best and sow chaos. Every round, one player is the President, and they select a Chancellor. The confirmation of the Chancellor pick is put to a vote: if passed, the President draws three cards from the deck, discards one, and gives the remaining two to the Chancellor to choose from. The Chancellor chooses from one of the two cards and places it on the corresponding board. Once the game is put into play, the finer points of the various strategies one could employ become evident.

For the more analytically-minded players, Secret Hitler is, at its core, a numbers game. There are more orange Fascist cards than blue Liberal cards in the deck (for a ratio of 11:6), and as cards are placed on either of the two boards (pictured above), the potential probabilities of what kinds of card could come next narrow. Players accurately tracking the ratio of Fascist to Liberal cards remaining can apply pressure to players lower in the round’s playing order.

As one could imagine, this tactic can prove troublesome for Fascist players. Fascist Chancellors lower in the playing order might have undue suspicion cast upon them for playing a Fascist card should the count favor a Liberal probability—no matter the reality of what cards the President gave them. Additionally, it might be harder for a Fascist President to claim they drew three Fascist cards and had no choice but to give the Liberal Chancellor two Fascist cards to choose from, forcing the placement of a Fascist card on the board.

However, even if a keen card counter numbers amongst the players’ ranks, there remains an element of subterfuge. In this situation, any Fascist player should lie when and where they can. If they are the President, they should lie about the identity of the third card that they discarded to further skew the count in the Fascist cards’ favor and make it easier for their Fascist brethren lower in the playing order to claim they had no choice to play a Fascist card. For a truly experienced Fascist, the optimal strategy is to become the card-counting player and gradually feed incorrect information to the rest of the players, preying on potential inattentiveness or numerical ineptitude.

This is just one specific scenario with specific players in mind. Due to its nature as a social deduction game, any and all strategies in Secret Hitler rely heavily on the make-up of the players in the group and their playstyles. Some players may live and die by the numbers. Others may forgo the strategy of counting cards entirely and base their assessment of other players’ honesty on social cues and whatever tells the player may have.

Some players may even have an advantage over the others by virtue of knowing some of the other players better. These players are better equipped to discern the other players’ play styles—either by virtue of having played Secret Hitler with them before or simply knowing them better in their personal lives. They may know that when their friend is a Liberal, they tend to be more soft-spoken or engage more passively in debates. Or, they may know that when their friend is a Fascist, their strategy is the exact opposite: the friend will insert themselves into every debate and voice their opinions freely.

This leads to the crux of a potential issue that players may have with Secret Hitler and other games that ostensibly favor such familiarity. To what extent does Secret Hitler rely on the social aspect of the term “social deduction?” Furthermore, does it truly matter? Should players agonize over the concept of fairness in a game where some players might derive an advantage from their familiarity with other players? What about situations where everyone knows each other equally and knows how the other players generally prefer to play—would this make the game stale?

In short, it’s complicated. On one hand, any game can and will become stale or boring the more it is played without any variation. That is inevitable. On the other hand, it would seem inadvisable for a game to hinge the majority of its enjoyability on an intense degree of interpersonal familiarity. Games could choose to prioritize such a mechanic and still be functional, but those games would likely not see much success as widely enjoyed party games or games to break the ice with new friends and acquaintances. They would likely be seen as games best-suited for established, close friends groups.

The perceived problem of players learning each other’s strategies and their behavioral patterns is something that could be “fixed” by the players themselves. Once made aware—whether it be through discussion or observation—players might deliberately toss up their playing strategies. They might experiment with new strategies, attempt different maneuvers, or lie more extravagantly. This may come at the expense of victory for a game or two (or three), but in the long run, this shake-up could lead to more victories down the road as other players become less sure of one’s social tells or strategies. It might seem dishonest to do this—it is lying, of a sort, but this is Secret Hitler. Lying is the name of the game.

Generally, social deduction games are responsible for providing a semi-flexible base and framework of rules for the players to adapt to their desires and playstyles. Players should still seek out the games whose basic premises interest them; one should not ask a game to be something different than what it is intentionally designed to be, especially when there are a multitude of games in existence that actually are the thing the player desires. However, social deduction games’ strength lies in an allowance for player mutability.

Shifting the onus from the game—so long as it has provided an adequate base—to the players to “shake things up,” as it were, is likely the most expedient solution to this perceived conundrum, particularly for social deduction games. The best—or the more commercially successful—social deduction games do not rely so rigidly on the players being familiar with one another. Any interpersonal familiarity is certainly no hindrance to the game’s enjoyability, and it might very well give the game a new edge of difficulty as players attempt to mask their tells from their friends, but in most cases, it is not absolutely integral to the game’s basic functionality. Secret Hitler is such a game where even if all social elements were to be stripped from it, there remain multiple opportunities for lies to be called out, numbers to not add up quite right, or for patterns of behavior within the span of a game to be established.

-Carrie Midkiff

Image source: https://medium.com/@mackenzieschubert/secret-hitler-illustration-graphic-design-435be3e3586c