by Katie Fraser

One of Twine’s most unique features is its low barrier to access, both for game creators and users. Making a game is so simple that even I, someone with no programming or game development experience, can operate Twine game creation with ease—all you need to know how to do is type and use the “[[]]” feature, which allows you to create a new branch. By dissolving the barriers to entry that exist in almost all other areas of game development, Twine games have created a more inclusive gaming space for communities who often feel their voices aren’t being heard (or even expressed) in the gaming sphere: namely women, the LGBTQ+ community, and racial minorities. Moreover, playing games on Twine is as easy as clicking your mouse… literally: all you have to do to progress in the game is either click or roll your cursor over a link (depending on the game). Thus, both users and creators of these games don’t need to be experts in the gaming world; instead, these experiences are open to everybody.

This low barrier to entry is an especially critical component of narrative games surrounding love and sex. Since the corporate video game industry is dependent upon public appeal to make money, many games that end up being funded affirm and reinforce heteronormative and societally acceptable narration and perspectives. Twine presents a different opportunity for game users and creators: given the absence of monetization, Twine game creators are free to explore topics considered to be “taboo” to today’s modern society. In deviating from societal norms, a few topics are continually brought to the table: queerness and sexual intimacy. Through games such as Queers in Love at the End of the World, players can experience queer love; meanwhile, games like Fuck That Guy offer an exploration of the taboo in sex, drawing a focus on graphic descriptions of gay sex and often including elements of BDSM. These gaming experiences allow for new understandings of communities that often go unheard or misrepresented in mainstream media, fostering empathy and acceptance among players.

Even Cowgirls Bleed (Christine Love, 2013)

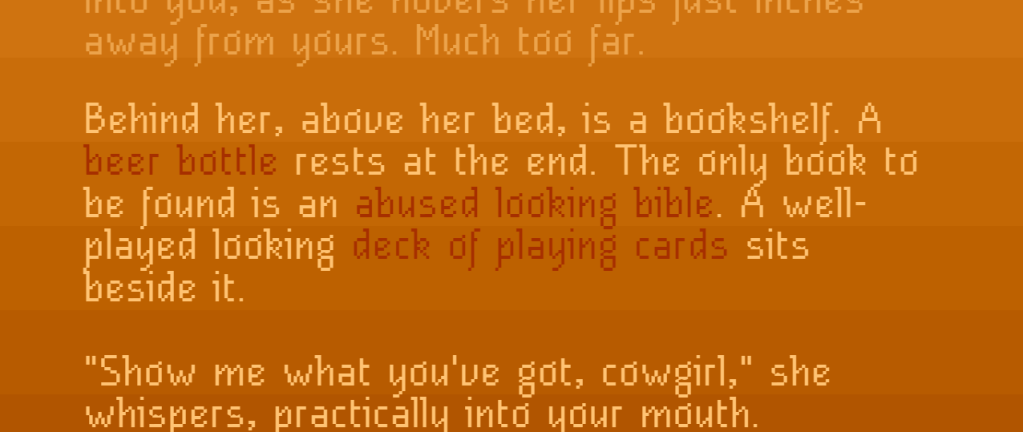

Even Cowgirls Bleed, ironically released on Valentine’s Day of 2013, is a second-person narrative game where you play a queer city girl moving out West to San Francisco. Instead of the normal mouse cursor, your cursor transforms into a crosshair of a gun, and players make choices by scrolling over, not clicking, different options. This represents both the trigger-happy nature of the protagonist, as well as the choices users can make throughout the game—all of them involving the protagonist’s gun.

Players are able to progress in the game through one of two choices: shooting (or at least attempting to shoot) at whatever the text is highlighting or putting your gun in your holster. Oftentimes, only one of these two choices is available for players, and they’re forced into an option. For example, at one point in the game, the protagonist is describing her transportation to San Francisco. The repetitive action of putting the gun in the holster, from left to right over and over again, uses the game mechanisms to transfer the impatience that the protagonist experiences to the player.

This lack of genuine choice that appears over and over again throughout the game may serve as a source of frustration for players, especially given the role that heightened autonomy often has in Twine games. This frustration is only exaggerated by the game’s conscious use of second-person narration: the game explicitly states that you are the character making the choices, but doesn’t allow you to actually choose. Even in circumstances where you may not want to shoot, your choice is made for you. One prominent example of this is a pivotal moment in the game: you’ve met a cowgirl who you’re genuinely interested in and she’s asking you to give her the gun. It seems as if this option is available—in the middle of other objects you can shoot, the text “Hand over the gun” is highlighted. However, you can’t access this choice. First of all, since it’s surrounded by the other decisions, you have to scroll over those to even get close to giving the gun to the cowgirl. Moreover, even if you think of the loophole of right-clicking your cursor to scroll over the other options without setting them off, your gun ends up going off while you attempt to give it to the cowgirl. Even when autonomy is seemingly offered, it’s then swiftly taken away.

Moreover, the game always ends in the same way: the protagonist scares her potential love interest away, shoots her own foot, and begins to bleed as the background turns red. No matter what choices you make, the outcome is always the same.

While this limited user autonomy does make for some irritation while playing the game, it also has a thematic purpose within a game: to situate players in the helplessness that many queer individuals experience. Queer individuals often face societal discrimination, marginalization, and a lack of control over their own narratives. Thus, the restricted agency in the game serves to parallel the broader challenges and power dynamics that many queer individuals encounter in their lives, where choices may feel constrained or overridden by external forces. In this way, Twine utilizes its unique game characteristics for a deeper portrayal of the queer experience.

Queers in Love at the End of the World (Anna Anthropy, 2013)

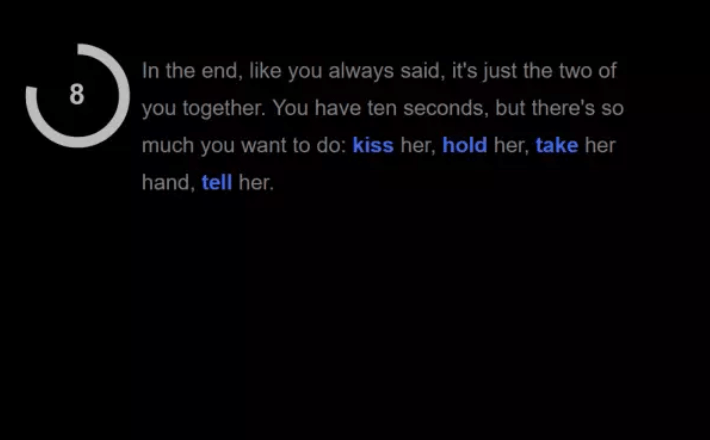

Queers in Love at the End of the World features a ten-second narrative, equipped with a timer on the left side of the user’s screen. During this time, players are faced with how to interact with their partner before “everything is wiped away.”

Through a huge variety of branching options, all starting with the choices of “kiss her,” “hold her,” “take her hand,” or “tell her,” players must navigate what they can truly do in this limited time frame.

The first time I played this game, I was barely able to finish reading the first page’s text before the game ended. The second time, I immediately clicked an option and was faced with the same problem—I couldn’t even finish reading before the game was over.

The ending remains the same no matter what you choose: it’s the end of the world and “everything gets wiped away.” However, while this may seem to take away autonomy from the user since they can’t affect the outcome, some sense of autonomy comes with the multitude of options offered. Each path seemed endless, and many times I couldn’t find a stopping point for a branch before the game was finished. Therefore, even though the game’s world will always end, players can make their own choices about how to interact with the protagonist’s partner in those final seconds, expressing their own feelings and desires through the game’s narrative. The game doesn’t allow players to change the world’s end, but it does give them the opportunity to shape the emotional connection the protagonist has with their partner.

These games show how the unique mechanisms of Twine allow love and sex-focused games to serve as powerful tools for challenging societal norms and promoting inclusivity within the gaming community and beyond.