by Austin Xie

Failure is sometimes cited as a fundamental part of games—after all, what is a game without the threat and challenge of failure? In fact, what is a story without that threat of failure for its characters? Of course, there are exceptions to both these questions, but the affective core of conflict generally remains the same: it is the prospect and possibility of losing that gives a problem stakes, and games have leveraged this since their inception.

Death and failure thus tend to constitute important mechanics in many games, but in a non-diegetic fashion. The main character is not “supposed” to die to some random small fry enemy in the “real” story, and thus the game is reset to a time before the player deviated from the canon, so that they can try again and again until they succeed.

Some games really streamline this process: Celeste resets the player instantly whenever they die attempting its difficult platforming, and Neon White provides a literal level reset key—bound to F by default, right next to its WASD movement controls—so that players can quickly get back to the start and try for faster level times. These mechanics are central to making both of these games work, but it’s not as if Madeline is dying over and over again as she attempts to climb Mt. Celeste, and neither is White really timing and doing his missions over and over again just to shave off an extra tenth of a second. The core gameplay loop of these games is non-diegetic (not that they need to be), but Elsinore handles this differently.

Elsinore plays from the perspective of Ophelia from Shakespeare’s Hamlet, who is trapped in a time loop during the days of the play’s (and thus the game’s) events. Players run around the castle Elsinore talking to its inhabitants, listening in on events, and trying to prevent tragedy, and over and over again Ophelia will die from one series of events or another, only to loop back to the beginning.

The core gameplay of the game, however, comes from the fact that Ophelia remembers these time loops—she retains the information she learns in previous loops, and can use that to further talk to people and manipulate the events happening throughout the castle. This is where Elsinore differs from most other games: her deaths and her failures are all part of the game, part of her experience, just as it is the player’s. It is this crucial mechanic that not only makes the game function, but also brings the avatar of Ophelia closer to the perspective of the player, further immersing them into the game.

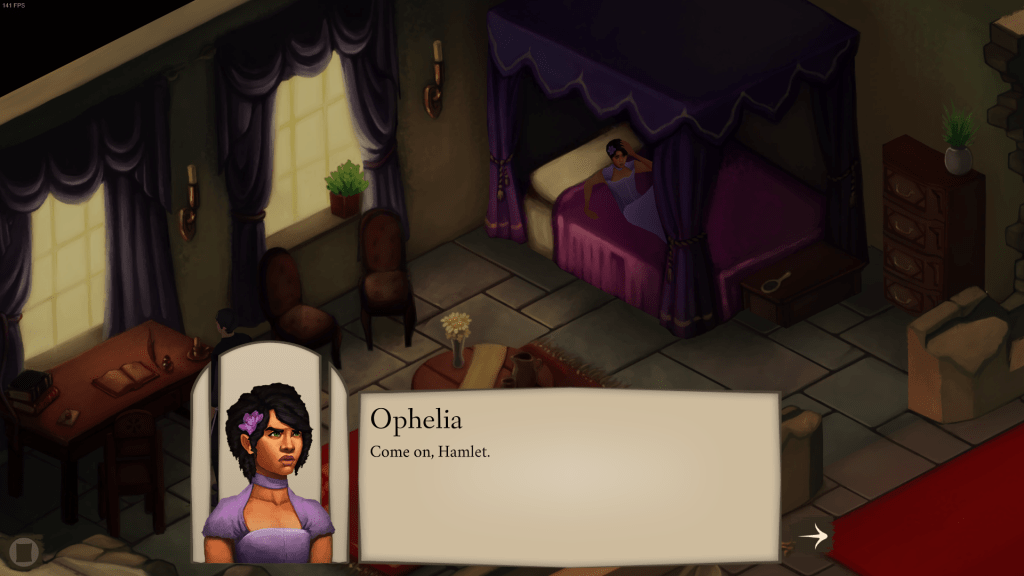

Every time loop opens in Ophelia’s bedroom, where Hamlet waits inside and, upon Ophelia’s waking, is ready to dive into crazed ravings regarding him meeting the ghost of his father—but as the loops continue, Ophelia begins cutting him off before he even begins, echoing exactly what’s sure to be the player’s annoyance with Hamlet’s dialogue. I, for one, skipped through it every time until Ophelia started doing it herself. It is details like these that help interconnect the player’s and Ophelia’s experiences in both directions, and really allow players to embody Ophelia, to feel what she feels and care about who she cares about, which makes the multiple endings to the game—all of which involve some sort of sacrifice—reflect on the player just as much as it does Ophelia in that timeline.

Despite this, the player’s feelings on the game’s characters can still veer towards the apathetic; because of the uneven experience and information between Ophelia and the player versus the rest of the cast (minus King Hamlet’s ghost and the playmaster Quince), Elsinore’s gameplay loop depends on completely manipulating the residents of the castle, and on sometimes sacrificing characters for information or to enact certain conditions in any given timeline. This is not conducive to a caring relationship between players and the characters, and the game knows this—in a timeline where Gertrude kills herself, King Hamlet advises Ophelia to close her heart to Gertrude’s suffering: she will witness thousands of her loved ones die over the course of the loops. This gradual detachment plays into the aforementioned theme of sacrifice in the game’s endings, and creates this sense of encroaching disillusionment throughout the play, which really helps convey the tragedy of its story.

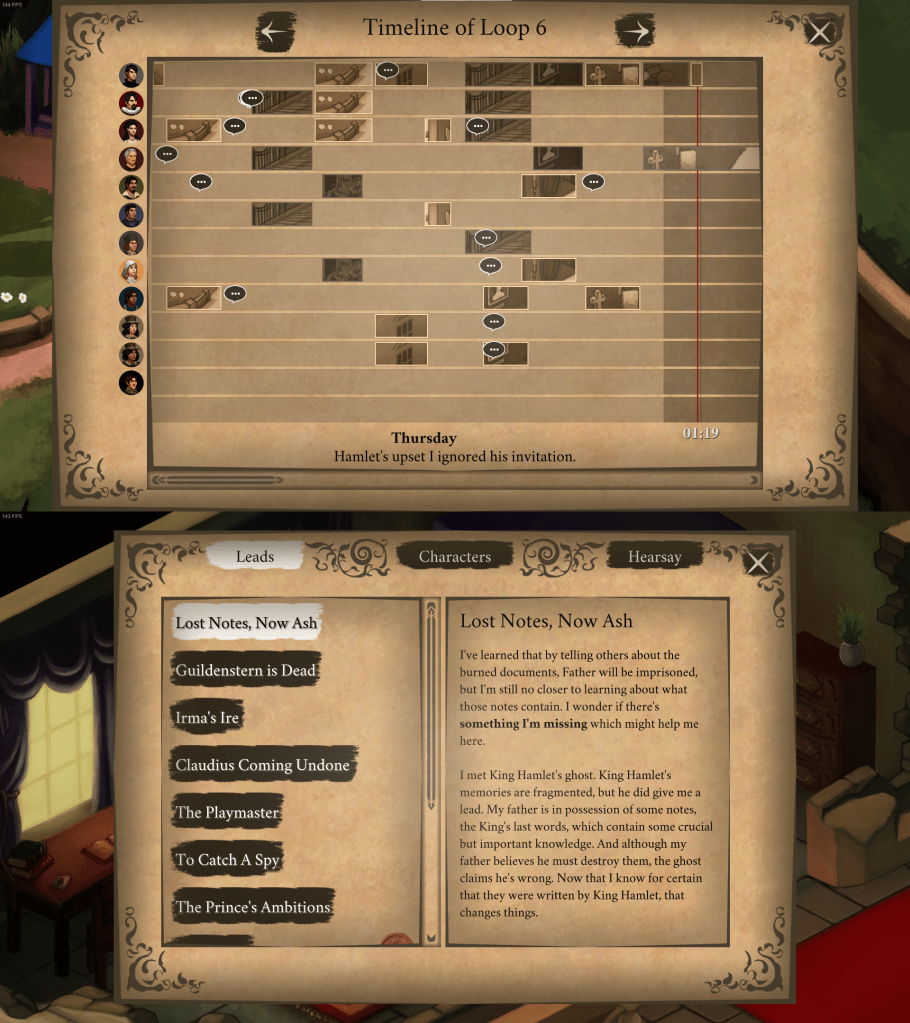

On a more technical level, Elsinore is about navigating databases of information, and its systems are designed to support this. Players have access to a timeline, chronicling both past and future events in the current loop, alongside the option to reference timelines of prior loops. They also can reference three other sources of information: a “leads” page, which lists and describes unresolved questions and problems that Ophelia needs to investigate or address; a “characters” page, which lists (and actively updates with) all known characters alongside information about them and their behavior; and a “hearsay” page, which lists all the information Ophelia knows and can tell people about. In addition to this is also the player’s growing database of knowledge surrounding how characters react to certain information–Hamlet, for instance, will become become uninteractable and resolved to kill his uncle, King Claudius, if Ophelia tells him that she knows Claudius killed King Hamlet.

Compared to other similar games, such as IMMORTALITY, The Infectious Madness of Doctor Dekker, or even Galatea, Elsinore‘s database navigation is much more complicated. Much of the difficulty in those games comes from trying to find and/or elict information, and though obviously this is present in Elsinore as well, most of its difficulty and frustration actually comes from applying that information and trying to create the precise circumstances needed to achieve an ending. This reflects its complexity–or rather, the complexity of the real world interactions the game simultaneously represents.

Winning the game is not so simple as directly telling characters the information they need to know–going around telling people about the time loop and the things that occur will only get Ophelia sent away for her perceived insanity. Navigating, investigating, and exploring the gamespace of Elsinore is supposed to be hard, complicated, and sometimes frustrating, because those feelings are so central to its story. There are constantly real consequences to things Ophelia tells people–it is not like Galatea where most dialogue will not phase the titular character enough to cause significant change, nor is it like Doctor Dekker where players can fiddle around with what exact questions they’re asking their patients, and even jump from one mood to another by interjecting an emotional conversation with a random other question. One wrong move in Elsinore can ruin an entire timeline, forcing Ophelia to either play out a doomed scenario, gathering whatever other information she can, or an early reset–the button to which is a skull, by the way–and another attempt from scratch.

Ultimately, Elsinore is about failure, consequence, sacrifice, and tragedy. Defying those things is nigh impossible, and even a success is not perfect. The game’s mechanics are designed to demonstrate that, to provide an experience proving that, and so it fosters those feelings in the player throughout the game as they try desperately to unweave the tanglings of the world and find a golden path forward.