by Chad Berkich

You walk into a room, and are faced with a choice: two doors, two divergent paths that will determine the course of the game. The Narrator instructs you to go left. What do you choose?

This decision is the centerpiece of The Stanley Parable. As stated in the Museum, “the rest of the game emerged as an extension of [the two doors], an exploration of the contradiction this room posed.” Considering the limited interaction and variety of endings, the game is essentially a series of choices that the player makes which leads them to an ending. The game then restarts so that a new path may be taken.

However, the game’s central thesis is that these choices aren’t really choices. The paradox of the aforementioned room is that, while two options are technically afforded to the player, neither is a choice in the truest sense; both are just paths laid out by the developer for the player to follow, two possible avenues for the story to continue along. Therefore, the only meaningful choice we have as players is to “Turn off your Nintendo Switch. There’s no other way to beat this game. As long as you move forward, you’ll be walking someone else’s path. Stop now, and it’ll be your only true choice,” as stated during the Museum ending.

Some have posited that the point of this thesis is to demonstrate the futility of playing video games, that the thesis of the game is pointing to the meaninglessness of the experience. Simultaneously in this view, the game is viewed as a failure because the players find the experience meaningful with its varied, typically humorous, endings.

I would argue, however, that this is the exact opposite of what the game is trying to demonstrate. While it is true that there is very little original agency in the game, that does not make the player’s experience with it meaningless. Rather, the satirization in the game is the idea that there are no original choices in games, even though they are passed off as original, but that does not make the experience any less meaningful.

For example, consider the Bomb Ending. This ending is achieved by turning back on the mind control machine. When the player chooses this, a timer is started as the Narrator admonishes them, which eventually leads to an explosion and Stanley’s death. Despite the different colors and numbers appearing on the screens, there is no way for the player to stop the detonation—their fate has been sealed. However, when I played, I was unaware of this and futily attemptted to find a way to escape. The urgency and worry I felt as I tried to find a way to escape was a real, emotional response. Even though the response is “manufactured” by the game, it is genuine.

For another example, consider the Phone Ending. When the player picks up the phone, it transports the player to outside of your apartment, where Stanley’s wife talks to him from inside before it is revealed to be the Narrator imitating her. If the player attempts to escape, a wall is placed to block them. Moving inside the apartment, the Narrator details the metaphorical death of Stanley as the player is forced to keep pushing buttons, transforming the apartment into Stanley’s office.

This ending is esoteric and strange, and particularly caught me off guard the first time I experienced it. It also delves into psychological territory, with the Narrator discussing how Stanley always did what he was told until he dreamed up a scenario in which he would have agency. It likewise supports the original thesis of there only being one true choice.

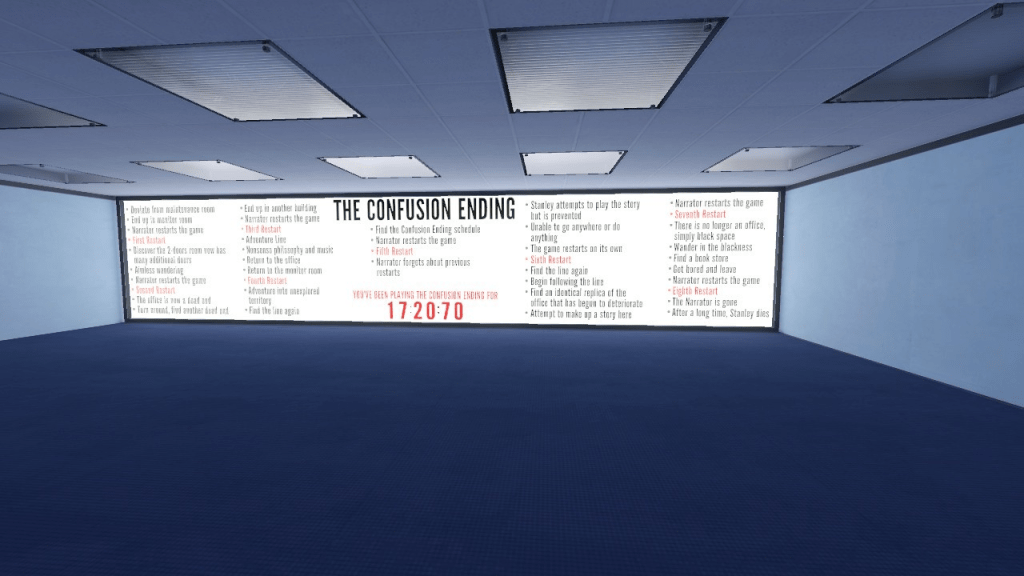

Finally, consider the Confusion Ending. This ending is achieved by going down the elevator between the left and right hallway. The game ends up spoiling itself, and the Narrator restarts it. However, this causes the game to break by introducing more doors to the seminal choice. When the game restarts again, there are no doors. On the next restart, the Narrator introduces The Stanley Parable Adventure LineTM, which is supposed to lead to the story. Music also plays as you follow the LineTM. However, when the LineTM ends up self-intersecting, the Narrator restarts one final time, deciding to ignore the line which occasionally intersects with the path. Eventually, this leads to a room with the Confusion Ending.

This ending is notable for the humor in it. The doors multiplying and then disappearing, the introduction of The Stanley Parable Adventure LineTM and itsTM associated music, and the list detailing the Confusion Ending were all genuinely laugh-out-loud moments. The ending continued to become more and more absurd, and that made the comedy extremely memorable and effective.

What these endings, which are only a sample of The Stanley Parable’s possible conclusions, represent is how the game creates meaning while satirizing choice. While the player does not have any original agency over the stories, the stories still have an effect on the player. There is an anxiety to the Bomb Ending, an eeriness to the Phone Ending, and a comedy to the Confusion Ending, all of which are effective in eliciting the intended emotion from the player. These are also notably varied endings, meaning the game is capable of eliciting a range of emotions. This is one of the primary purposes of narrative, to elicit an emotion or thought in the person experiencing it. The Stanley Parable’s endings do have meaning in a traditional, narrative sense.

What the game is satirizing, then, is the idea of original agency in games. The idea of the player having control over how the narrative plays out has become a key feature in many games; consider Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic’s morality system or NieR: Automata’s different endings. What The Stanley Parable argues, then, is that these are not really players having control over the games, but rather walking a path the developer has predetermined. These games only offer the illusion of original agency. However, this does not mean that the game is meaningless or bad, as shown with The Stanley Parable’s many different narratives.

The game also argues this with the specific idea of constrained choices as demonstrated by the other games featured. In the Other Games Ending, the player is briefly able to play Firewatch and Rocket League. Firewatch is an open world game, so while there is a general path to follow, it is much less strict than The Stanley Parable. Rocket League is a soccer game, so while the player is not afforded an open world, the player’s actions have a much more important effect on gameplay as well as more options to interact with the game.

Thus, The Stanley Parable’s thesis is that there is only one true choice, whether to play the game or not. However, this thesis is not meant to be completely universal, as shown with Firewatch and Rocket League, nor is it a matter of saying games are meaningless. Rather, The Stanely Parable subverts and satirizes the trope of choice in video games in order to demonstrate how games use an illusion of agency, while simultaneously creating narrative meaning.